Check out Signed Cards and Game Used Items by CURT FLOOD

For decades, baseball’s Reserve Clause bound a player to a team unless he was traded, sold, or released. A player had zero bargaining power at contract time other than refusing the owner’s terms, forcing him to quit baseball.

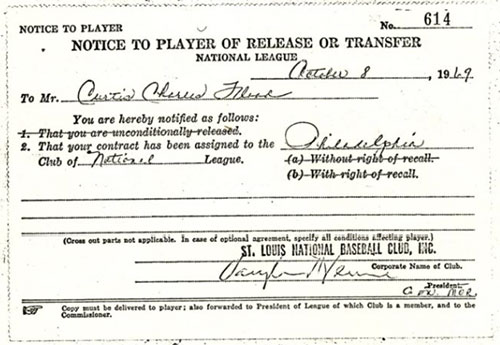

The “status quo” of the Reserve Clause received its first litmus test following a trade on October 7, 1969, in which St. Louis Cardinals star outfielder Curt Flood was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies along with Tim McCarver, Joe Hoerner, and Byron Browne for Richie Allen, Cookie Rojas, and Jerry Johnson.

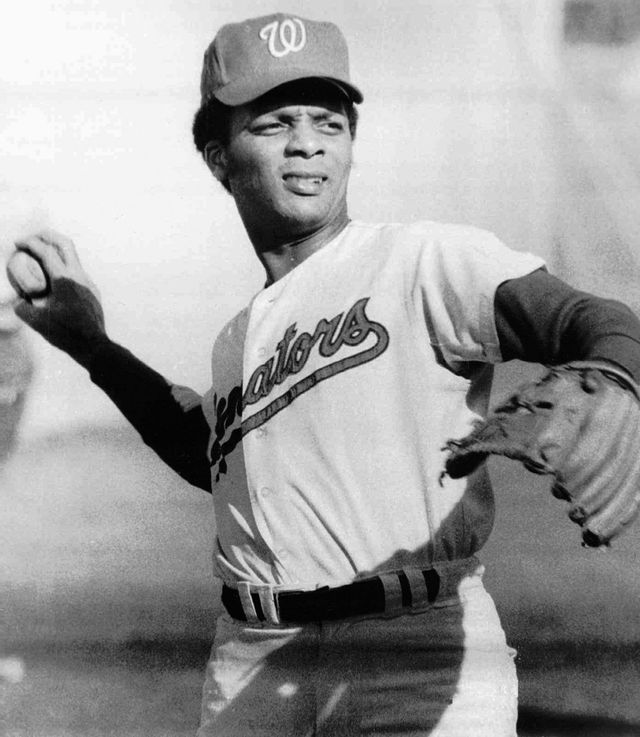

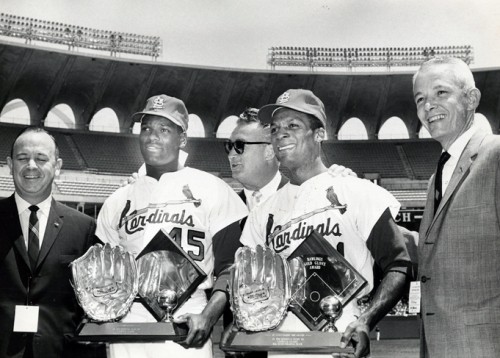

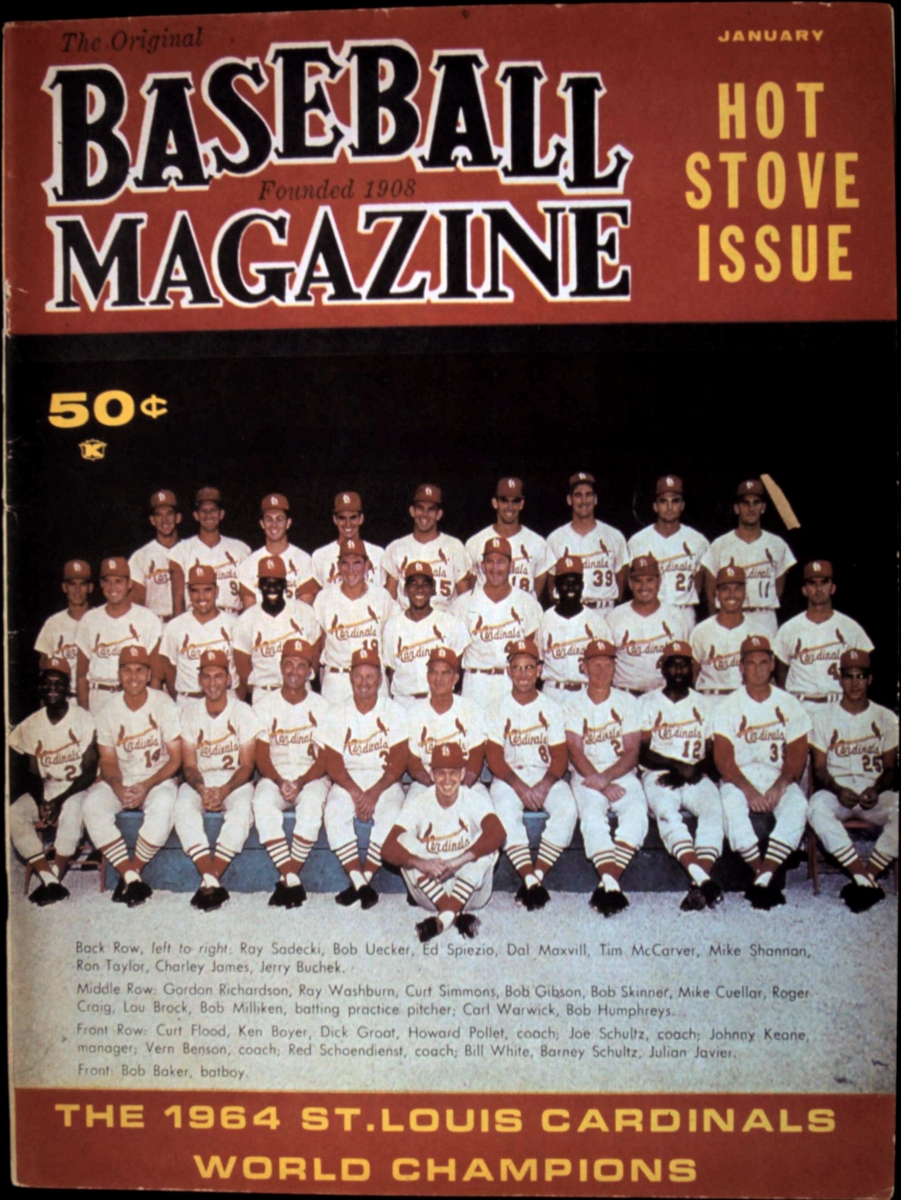

Born in Houston, Texas, in 1938, and raised in Oakland, California, Curt Flood attended West Oakland’s McClymonds High School, playing in the same outfield as fellow African-Americans Vada Pinson and Frank Robinson. All three were gobbled up by the Cincinnati Reds for $4,000 each. The Reds kept Pinson and Robinson but let Flood go to the Cardinals in December 1957 as part of a five-player deal. In St. Louis, the 5-foot-9, 165-pound Flood excelled in center field by winning seven straight Gold Gloves from 1963 to 1969. He also hit .300 on six occasions and contributed to three National League pennants and two World Championships. “I gave a hundred percent all the time,” Flood said years later.

When the October 7, 1969, trade transpired, Flood was upset for being notified by a subordinate member of the Cardinals management, not GM Bing Devine himself. Flood had the suspicion he was let go because he had wanted another $10,000 to bring his yearly salary to an even $100,000, and that he had criticized management in the press for making moves part-way through 1969 in anticipation of the team not appearing in the World Series, after back-to-back appearances in 1967 and 1968.

Popular Posts

Best Youth Baseball Bats

Best BBCOR Bats

Best USA bats

Best Softball Bats

Best Wood Bats

Thinking it through carefully, Flood decided that after 12 years in St. Louis, he was not going to pick up and move his family. He didn’t like Philadelphia. The Phillies were horrible, and their dilapidated home field, Connie Mack Stadium, should have been torn down long ago. Also, Flood didn’t like how the black players were treated there. The best example was the other big name in the trade, Richie Allen, who had taken so much verbal and garbage-throwing abuse in Philly that he began wearing a batting helmet while playing first base. Flood believed he should have the right to negotiate with other clubs for his services the same way individuals had the freedom to do in other vocations. Contracts should have a beginning and an end, he thought. To the Cardinal outfielder, the Reserve Clause was slavery.

Flood contacted Marvin Miller, executive director of the newly established, two-year-old Major League Baseball Players Association. Miller informed Flood that a Reserve Clause fight could not be won and that it would certainly ruin the player’s career in the process. Flood asked if it would benefit players in the future. Miller said it would. If Flood wished to pursue the legal battle, Miller promised Players Association funding to handle the legal costs.

Flood then wrote MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn the following letter on December 24, 1969:

After twelve years in the major leagues, I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the several States.

It is my desire to play baseball in 1970, and I am capable of playing. I have received a contract offer from the Philadelphia club, but I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decision. I, therefore, request that you make known to all Major League clubs my feelings in this matter, and advise them of my availability for the 1970 season.

As expected, Kuhn denied Flood’s request for free agency. Flood then filed a $1 million lawsuit against Kuhn and Major League Baseball for violating U.S. antitrust laws. Players Association reps supported Flood, while many rank-and-file players sided with the owners. A few months later, at the start of the 1970 season, the Cardinals sent the Phillies two minor leaguers to compensate for Flood’s refusal to report. Then, later that same year, the owners voted in the “10/5 Rule.” Nicknamed the “Curt Flood Rule,” it stated that a player with 10 years of Major League service and the last five years with the same club could veto any trade. Too-little, too-late for Flood. In November, the Phillies traded him to the Washington Senators for three players. Flood played 13 games in 1971, hit .200, then retired with a lifetime .293 batting average.

The long-anticipated trial finally began in New York City before the U.S. Supreme Court on March 20, 1972. Testifying on Flood’s behalf were former star players Hank Greenberg and Jackie Robinson and former owner Bill Veeck. No active players came to Flood’s defense or even attended the trial for fear of reprisals. When the ruling came down on June 19, 1972, the owners won by a 5–3–1 margin. The panel of judges cited earlier challenges to the Reserve Clause in 1922 and 1953, whereby the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Sherman Antitrust Act as not applicable to baseball. Flood lost, but his challenge banged a good-sized dent in the owners’ armor.

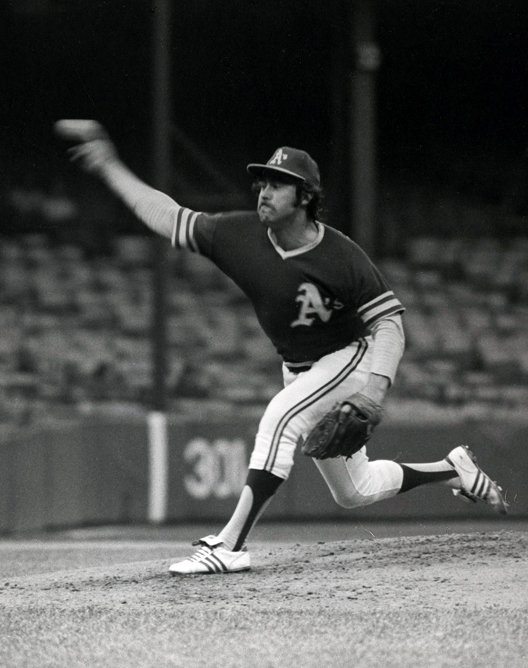

Two more significant legal cases soon followed. The first one involved Oakland Athletics pitcher Jim “Catfish” Hunter, who had just come off a tremendous 1974 season in which he won the American League Cy Young Award with 25 wins and a 2.49 ERA and helped his team to a third straight World Series championship. It was also his fourth consecutive 20-win season. Paid $100,000 for the year, $50,000 of it—as per his contract—was supposed to be placed in a North Carolina bank in monthly payments on an insurance annuity. But it didn’t get there. Hunter asked A’s owner Charlie Finley about it on several occasions. “It’s in the mail,” was Finley’s reply.

With Marvin Miller’s help, Hunter filed for arbitration that December and won on a clear violation of his contract agreement. Major League Baseball declared Hunter a free agent, sending shockwaves throughout the sports world. In a blink of an eye, 23 of 24 teams made bids for the pitcher’s services. Inside two weeks, Hunter signed a five-year contract with the New York Yankees for $3.35 million. He went out and won 23 games in 1975, his fifth straight season winning 20 games, then he helped the Yankees win three straight pennants from 1976 to 1978.

Next, prior to the 1975 season, pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally were heavy into contract squabbles with their respective teams, the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Montreal Expos. Both players decided to play the season anyway. Under the Reserve Clause rules, they would each be paid their previous contract. McNally left the Expos in June after a 3–6 record and planned to retire by the end of the year. Messersmith finished with 19 wins. As soon as the season ended, Marvin Miller urged the two pitchers to file grievances through the Players Association, arguing that a disputed contract should be renewed for only one year, and after that a player should be declared a free agent. This was a direct challenge to the owners’ thinking that contracts were indefinite. Even though McNally still planned to retire, he was important to the cause. Two players were better than one.

On December 23, 1975, baseball’s arbitrator Peter M. Seitz sent even more shock waves through the sports world when he agreed with the Players Association. By refusing to sign, both pitchers were declared free agents and could sell their services to any team. Via this historic judgment, the owners finally caved in. At first, the decision didn’t bring about the total free agency we see today. Management and Marvin Miller worked out a deal granting the players full negotiating freedom after six MLB seasons. McNally retired as expected, but Messersmith signed a multi-year contract with the Atlanta Braves. Over the next few years, player salaries jumped from a $45,000 average in 1975 to over $2 million by 2002.

Curt Flood left the country following the 1972 ruling. An artist in his spare time, he ran a bar on the Spanish island of Majorca and returned to Oakland four years later. In 1978, he joined the Oakland Athletics broadcasting team. Flood died of throat cancer on January 20, 1997. Nine years later, his 1989 oil painting of Joe DiMaggio sold at auction for $9,500. Every Major Leaguer since 1975 should be grateful to Curt Flood, a star player who helped shatter the Reserve Clause barriers for the sake of future players.

After retirement, Mickey Mantle was asked countless times how he would’ve handled free agency if he was playing in the modern era. He never wavered in his reply. “I’d walk into the owner’s office and say, ‘Hi yuh, partner.’”