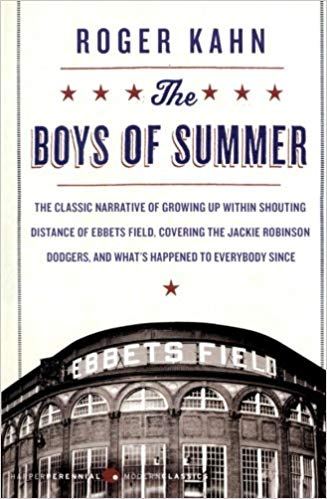

Reading this nostalgic book following its 1972 release, I was jealous of its author, Roger Kahn. Why? Because I wish I could have been in his boots writing about those pennant-winning years of the early 1950s Brooklyn Dodgers as he had done for the New York Herald Tribune, then later getting the once-in-a-lifetime chance to interview a few of the same Dodgers stars in the early 1970s, while they were still alive, long after their playing days had ended. Kahn then put these two-part experiences in book form: The Boys of Summer. Lucky guy. He had actually traveled around with an iconic integrated team that played in an iconic park, Ebbets Field, during an iconic time, the Fabulous Fifties.

What a start to a writing career! It doesn’t get any better than that!

Born in Brooklyn to a Jewish family in 1927, Kahn began the book by describing his boyhood experiences growing up a Dodgers fan listening to legendary broadcaster Red Barber on the radio. Kahn moved up from a copy boy in his late-teens with the Herald Tribune to cover the Dodgers for the 1952 season. As a novice writer, he received plenty of advice from the New York writers during his first spring training: in particular, Harold Rosenthal and the fiery Dick Young. Rosenthal told the young Kahn to not use the word “wow,” to not talk too fast, and to cut his hair shorter. “This is no place for a Jewish musician,” were Rosenthal’s words.

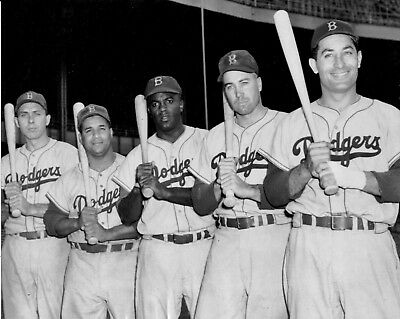

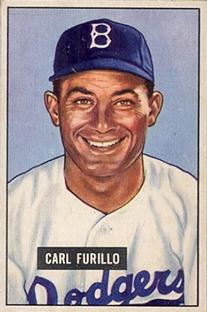

In Florida, Kahn was quickly introduced to Pee Wee Reese, Jackie Robinson, Clem Labine, Carl Erskine, Carl Furillo, Preacher Roe, Duke Snider, Gil Hodges, Roy Campanella, and many more. Furillo took special interest in Kahn. Nicknamed “Skoonj,” Furillo sized up the short, 140-pound Kahn and immediately nicknamed him “Meat.”

Kahn wrote about the integrated Jackie Robinson Dodgers with hardcore passion. He informed the reader about life on the road, with the train being the players’ world: where they ate, slept, read newspapers, and played cards. In the era before passenger aircraft, they got to know each other in a way not seen in sports today. Heck, St. Louis was the westernmost point in the National League. Kahn saw firsthand how the players truly integrated within the team. Hardly ever did two African-Americans sit together in the dining car. Robinson, Kahn had heard, ordered African-American players to “spread out.”

The Boys of Summer was one of the first baseball books where I saw F-bombs and other choice swear words—still somewhat new in print at the time—from players and especially Dodgers Manager Charlie Dressen. But that’s sports. I know. I played too. Kahn also showed a human side to different players. Erskine liked poetry, and on one occasion he recited some of it for Kahn. Snider was often booed by hometown fans because they thought he was a loafer. Some writers, meanwhile, saw him as a whiner because he got down on himself during slumps. Robinson was a serious competitor and defender of his race, sometimes too serious. But much-respected team leader and captain Pee Wee Reese always seemed to make his teammate grin after his many comical remarks during those tense moments.

During his first spring training, Kahn was asked to “stand in” on one occasion in the batter’s box while second-string catcher Al Walker warmed up pitcher Clem Labine. Labine’s first pitch—a fastball—left the writer in awe. Although, he said, Labine was not the fastest pitcher on the team, the ball came toward him with a “whoosh,” followed by a buzzing sound like hornets, before it “exploded” into Walker’s mitt. Now, that was a great description of a Major League fastball.

To Kahn, the Dodgers were a squad both talented and disappointing at the same time. A team well followed across the country by both blacks and whites, they were great but not the best. In the two years that Kahn covered them, they won the National League pennant back to back, only to lose to the New York Yankees in seven and six games, respectively. Dodgers pitching let them down. And Yankees pitching neutralized the mighty Dodger bats.

Similar: Managing MLB Teams: Then and Now

The second part of the book, called “The Return,” was Kahn’s in-depth interviews in 1971 with 13 ex-players. A lot had happened—good, bad, and so-so—since each one had retired. In order in the book, they were: Labine, George Shuba, Erskine, Andy Pafko, Joe Black, Roe, Reese, Furillo, Hodges, Campanella, Snider, Robinson, Billy Cox, and even owner Walter O’Malley, who was still running the Dodgers out of Los Angeles, after he had moved them from Brooklyn in 1957.

At the time, most of the players were working. Labine was a businessman in Woonsocket, Rhode Island . . . “Shotgun” Shuba was a US Post Office supervisor in Youngstown, Ohio . . . Black was with Greyhound in Chicago . . . Hodges was managing the New York Mets . . . Pafko lived in Noblesville, Indiana, and scouted for the Montreal Expos . . . Roe owned his own grocery store across the Arkansas line in Missouri . . . Cox tended bar in Newport, Pennsylvania . . . Furillo was installing elevators on the new World Trade Center in New York City.

On a sadder note, Campanella had been confined to a wheelchair after a car accident in early 1958. A diabetic with high blood pressure, Robinson was not well, having suffered through a recent heart attack. Even sadder, Hodges and Jackie both died the same year The Boys of Summer was released.

Two of the interviews were especially informative . . .

Shortly after he retired, Preacher Roe agreed to a Sports Illustrated article written by Dick Young in 1955 in which Roe let the readers know that the spitball was his money pitch, hoping that the article would help to legalize the pitch. But nothing came of it. Then 16 years later, he told Kahn exactly how he threw his pitch, the gum he used to get the most saliva, and his deceptive motions to keep the umpires from catching him.

My personal favorite was the Carl Furillo interview, achieved on one of the unfinished floors of the World Trade Center high above the streets of New York City. Kahn described for the readers how years before Furillo had owned right field at Ebbets Field, playing it as if it were a work of art. While opposing outfielders found the right-field corner a virtual hell on earth, Furillo faced it as a challenge for his unmatched work ethic. Early in his career, he had teammates Cox and Roe hit fly balls off the wall while Furillo would watch carefully, his mind tabulating the logistics of it like a computer.

The Ebbets Field corner was 19 feet of concrete with a 19-foot screen on top. And it sloped at an angle starting halfway up the concrete, then went straight up the rest of the way. Toward the power alley, in between this concrete-screen corner, the flat scoreboard with the Schaefer beer sign stood with a small section of screen on top to complete the near 40 feet of wall. There were dozens of angles that a ball could carom.

In time and with practice, Furillo knew them all, from the short 297 feet down the foul line out to the 376-foot power alley, where he approached Snider’s center-field territory. If the ball hit the screen, Furillo knew he’d have to run like mad towards it because the ball would drop dead. If the ball went off the concrete wall, Furillo would run toward the infield because the ball would shoot out like a rocket. All Furillo had to do then was nail any runner foolish enough to advance a base on him.

To date, The Boys of Summer has sold 3 million copies in 90 printings. On a Sports Illustrated2002 list of “The Top 100 Sports Books of All Time,” Kahn’s creation ranks in the two spot, one up on Jim Bouton’s Ball Four.

Early in the book, Kahn said, “As a young newspaperman covering the team in 1952 and 1953, I enjoyed the assignment, without realizing what I had.” He went on to say it was a lot of hard work and pressure, his days filled with deadlines, meeting train schedules, and having to scoop other writers to stay on top of things. But he must have loved it. And that is divulged in spades throughout the book.

In my opinion, The Boys of Summer is the ultimate portrayal of the Jackie Robinson Brooklyn Dodgers era. Yeah, I’m still jealous of Kahn 40 years later.

Credit: Stephanie Rogers (public domain)

P.S.—I wish I could’ve done book reports on a subject like this when I was in high school, instead of the boring ones I had to do.