“His fastball was like nothing I’d ever seen before. It really rose as it left his hand. If you told him to aim the ball at home plate, that ball would cross the plate at the batter’s shoulders. That was because of the tremendous backspin he could put on the ball.”

– Pat Gillick

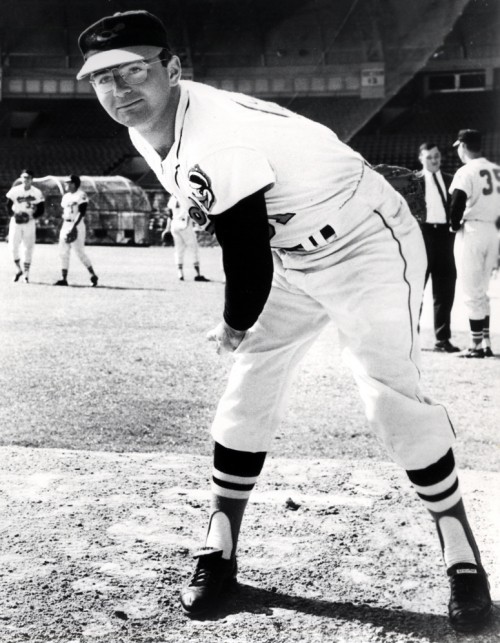

No one ever threw harder or had more of a star-crossed career than Steve Dalkowski. Old-timers love to reminisce about this fireballer and wonder what would have happened if he had reached the Major Leagues.

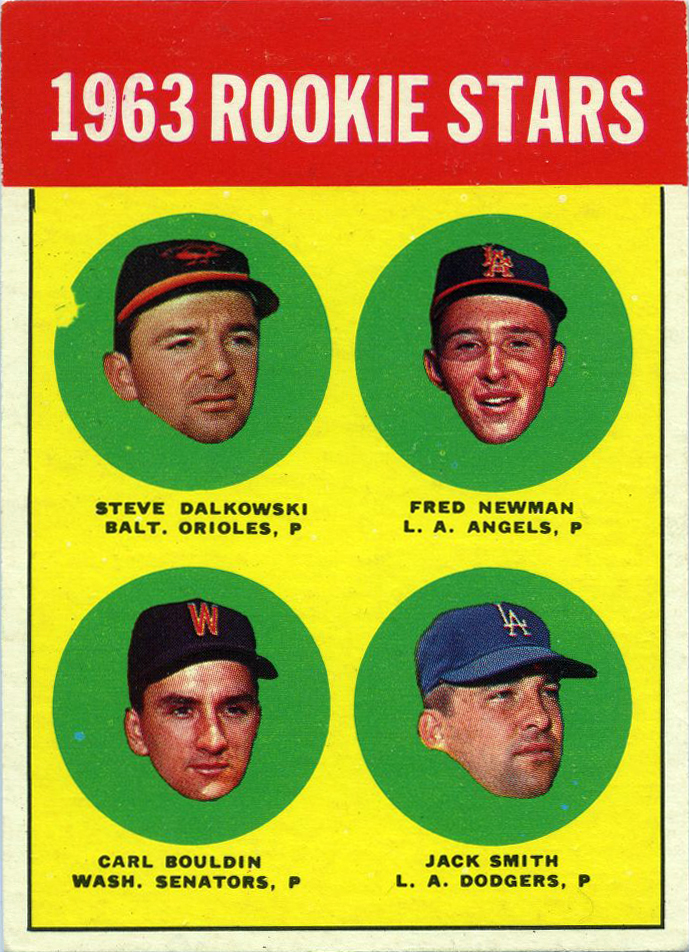

In 1963, near the end of spring training, Dalkowski struck out 11 batters in 7 2/3 innings. The myopic, 23-year-old left-hander with thick glasses was slated to head north as the Baltimore Orioles’ short-relief man. He was even fitted for a big league uniform. But in a Grapefruit League contest against the New York Yankees, disaster struck. Dalkowski fanned Roger Maris on three pitches and struck out four in two innings that day. Yet as he threw a slider to Phil Linz, he felt something pop in his elbow. Despite the pain, Dalkowski tried to carry on. But when he pitched to the next batter, Bobby Richardson, the ball flew to the screen. With that, Dalkowski came out of the game and the phenom who had been turning heads—so much that Ted Williams said he would never step in the batter’s box against him—was never the same.

Pat Gillick, who would later lead three teams to World Series championships (Toronto in 1992 and 1993, Philadelphia in 2008), was a young pitcher in the Orioles’ organization when Dalkowski came along. “I first met him in spring training in 1960,” Gillick said. “The minors were already filled with stories about him. How he knocked somebody’s ear off and how he could throw a ball through just about anything. He had a great arm but unfortunately he was never able to harness that great fastball of his. His fastball was like nothing I’d ever seen before. It really rose as it left his hand. If you told him to aim the ball at home plate, that ball would cross the plate at the batter’s shoulders. That was because of the tremendous backspin he could put on the ball.”

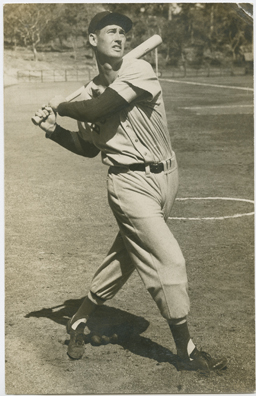

That amazing, rising fastball would perplex managers, friends, and catchers from the sandlots back in New Britain, Connecticut where Dalkowski grew up, throughout his roller-coaster ride in the Orioles’ farm system. Some advised him to aim below the batter’s knees, even at home plate, itself. Perhaps that was the only way to control this kind of high heat and keep it anywhere close to the strike zone. “Even then I often had to jump to catch it,” Len Pare, one of Dalkowski’s high school catchers, once told me. “That fastball? I’ve never seen another one like it. He’d let it go and it would just rise and rise.”

What made this pitch even more amazing was that Dalkowski didn’t have anything close to the classic windup. No high leg kick like Bob Feller or Satchel Paige, for example. Instead Dalkowski almost short-armed the ball with an abbreviated delivery that kept batters all the more off balance and left them shocked at what was too soon coming their way.

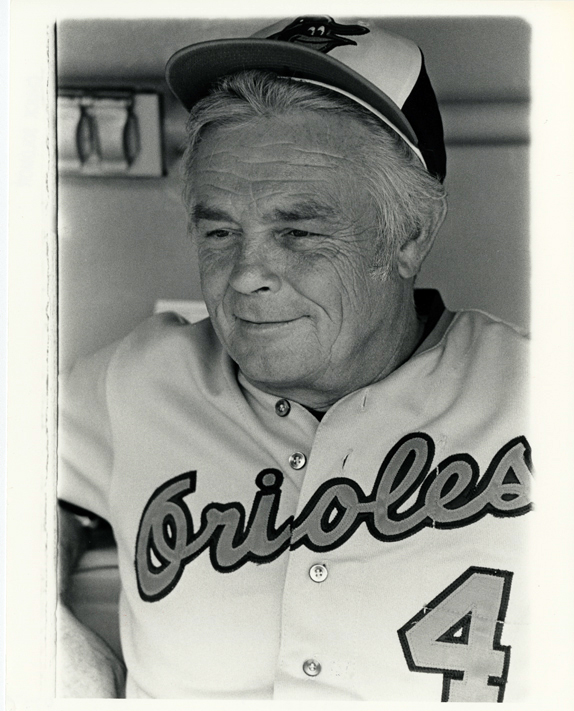

During his 16-year professional career, Dalkowski came as close as he ever would to becoming a complete pitcher when he hooked up with Earl Weaver, a manager who could actually help him, in 1962 at Elmira, New York. For the first time, Dalkowski began to throw strikes. During one 53-inning stretch, he struck out 111 and walked only 11.

In an effort to save the prospect’s career, Weaver told Dalkowski to throw only two pitches—fastball and slider—and simply concentrate on getting the ball over the plate. Dalkowski went on to have his best year ever. In his final 57 innings of the ‘62 season, he gave up one earned run, struck out 110, and walked only 21.

He appeared destined for the Major Leagues as a bullpen specialist for the Orioles when he hurt his elbow in the spring of 1963. The cruel irony, of course, is that Dalkowski could have been patched up in this day and age. Tommy John surgery undoubtedly would have put him back on the mound. Perhaps he wouldn’t have been as fast as before, but he would have had another chance at the big leagues.

Popular Posts

Best Youth Baseball Bats

Best BBCOR Bats

Best USA bats

Best Softball Bats

Best Wood Bats

Yet when the Orioles broke camp and headed north for the start of the regular season in 1963, Dalkowski wasn’t with the club. Instead, he started the season in Rochester and couldn’t win a game. From there he was demoted back to Elmira, but by then not even Weaver could help him. In what should have been his breakthrough season, Dalkowski won two games, throwing just 41 innings. His legendary fastball was gone and soon he was out of baseball.

At loose ends, Dalkowski began to work the fields of California’s San Joaquin Valley in places like Lodi, Fresno, and Bakersfield. He became one of the few gringos, and the only Polish one at that, among the migrant workers. During this time, he became hooked on cheap wine—the kind of hooch that goes for pocket change and can be spiked with additives and ether. White port was Dalkowski’s favorite. In order to keep up the pace in the fields he often placed a bottle at the end of the next row that needed picking. That gave him incentive to keep working faster.

Dalkowski picked cotton, oranges, apricots, and lemons. He married a woman from Stockton. After they split up two years later, he met his second wife, Virginia Greenwood, while picking oranges in Bakersfield. But none of it had the chance to stick, not as long as Dalkowski kept drinking himself to death. He was arrested more times for disorderly conduct than anybody can remember. He was sentenced to time on a road crew several times and ordered to attend Alcoholics Anonymous. For years, the Baseball Assistance Team, which helps former players who have fallen on hard times, tried to reach out to Dalkowski. This was how he lived for some 25 years—until he finally touched bottom. In 1991, the authorities recommended that Dalkowski go into alcoholic rehab. But during processing, he ran away and ended up living on the streets of Los Angeles.

“At that point we thought we had no hope of ever finding him again,” said his sister, Pat Cain, who still lived in the family’s hometown of New Britain. “He had fallen in with the derelicts, and they stick together. We thought the next we’d hear of him was when he turned up dead somewhere.

On Christmas Eve 1992, Dalkowski walked into a laundromat in Los Angeles and began talking to a family there. They soon realized he didn’t have much money and was living on the streets. The family convinced Dalkowski to come home with them. In a few days, Cain received word that her big brother was still alive. Soon he reunited with his second wife and they moved to Oklahoma City, trying for a fresh start. But within months, Virginia suffered a stroke and died in early 1994.

That’s when Dalkowski came home—for good. With his family’s help, he moved into the Walnut Hill Care Center in New Britain, near where he used to play high school ball. Slowly, Dalkowski showed signs of turning the corner. One evening he started to blurt out the answers to a sports trivia game the family was playing. Bill Huber, his old coach, took him to Sunday services at the local Methodist church until Dalkowski refused to go one week. His mind had cleared enough for him to remember he had grown up Catholic.

Less than a decade after returning home, Dalkowski found himself at a place in life he thought he would never reach—the pitching mound in Baltimore. Granted much had changed since Dalkowski was a phenom in the Orioles’ system. Home for the big league club was no longer cozy Memorial Stadium but the retro red brick of Camden Yards. On September 8, 2003, Dalkowski threw out the ceremonial first pitch before an Orioles game against the Seattle Mariners while his friends Boog Powell and Pat Gillick watched. “I bounced it,” Dalkowski says, still embarrassed by the miscue. Yet nobody else in attendance cared. “He was back on the pitching mound,” Gillick recalls. “Back where he belonged.”

———————————————————————————————————

Whenever I’m passing through Connecticut, I try to visit Steve and his sister, Pat. It’s comforting to see that the former pitching phenom, now 73, remains a hero in his hometown.

A few years ago, when I was finishing my book High Heat: The Secret History of the Fastball and the Impossible Search for the Fastest Pitcher of All Time, I needed to assemble a list of the hardest throwers ever. Not an easy feat when you try to estimate how Walter Johnson, Smoky Joe Wood, Satchel Paige, or Bob Feller would have done in our world of pitch counts and radar guns.

But that said, you can assemble a quality cast of the fastest of the fast pretty easily. Include Nolan Ryan and Sandy Koufax with those epic fireballers. Then add such contemporary stars as Stephen Strasburg and Aroldis Chapman, and you’re pretty much there.

For a time I was tempted to rate Dalkowski as the fastest ever. The stories surrounding him amaze me to this day. Yet it was his old mentor, Earl Weaver, who sort of talked me out of it. “It’s tough to call him the fastest ever because he never pitched in the majors,” Weaver said. “How do you rate somebody like Steve Dalkowski? That’s tough to do.

When I think about him today, I find myself wondering what could have been. That’s where he’ll always be for me. What could have been.”