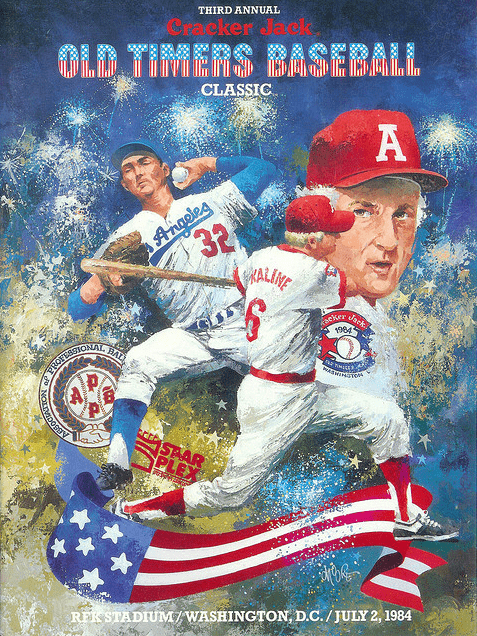

Between 1982 and 1990, an annual old timers game was played, first in Washington, D.C., and then in Buffalo, New York—an event that drew national attention from its very first inning.

It was known as the Cracker Jack Old Timers Baseball Classic, and it was the brainchild of former Atlanta Braves Vice President Dick Cecil.

“I missed seeing the old guys, and I wanted to stage a real game, not a two-inning affair where everyone hit once,” he recalled. “I wanted a game where the players would feel competitive once again.”

With that in mind he took the idea to Ketchum Communications, whose client, Borden, owned Cracker Jack. The snack, part of the “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” lyrics, had lost some of its baseball identity over the years, and its CEO, Frank Forrestal (son of FDR’s naval secretary, James), saw this as a great opportunity for his brand.

“Our presentation was 15 minutes long,” said Cecil. “They were aboard before we walked into the room. Most of the 15 minutes were spent talking about players to invite. I thought, “Is it always this easy?”

Cecil enlisted the partnership of the Association of Professional Baseball Players of America (APBPA), an organization with an all-star advisory board under the leadership of Chuck Stevens. Stevens, now 96, played three seasons for the St. Louis Browns in the 1940s. With the charitable component of APBPA added, word quickly spread among retired players that this was going to be a significant and fun event.

The placement of the game in RFK Stadium in Washington added to the significance. RFK had not had a baseball event since the Washington Senators fled to Texas after the 1971 season. While the Redskins still played football there, Washington baseball fans were hungry for a revival—even for a day. All the pieces were falling into place.

The missing element was support from Major League Baseball, even as Commissioner Bowie Kuhn had his heart in his hometown of Washington and a longing to return the game there. “His PR guy, Bob Wirz, told him this was not a good event to connect with, and so we had to go without MLB,” said Cecil. “As a result, we designed our own uniforms—National and American—and the players wore those.” Some of them have brought big money on the auction circuit in the years that followed because they had their names on the back.

Cecil wanted some special touches. The games would be five innings, not two, and would call for good competition and strategy. The players would be introduced one at a time, emerging from the dugout to cheers, and then returning. There was no lining up along the baselines. Robert Merrill agreed to do the National Anthem if he could have a uniform with No. 1½. ESPN, in just its third year of operations, made a deal to televise the game and signed up Red Barber for the first cablecast.

Cecil appointed an advisory committee that helped with player selection, and I was honored to be part of that committee. Stevens would manage the American League team, and Tal Smith the Nationals.

The players each received $1,000 plus travel expenses. No one got more—and the only player who appeared in all nine games was Joe DiMaggio. He loved the event, was at his friendliest with the old timers and the media, and really had a great time. The 1990 game was believed to be the last time he wore a uniform, although he no longer took a turn at-bat.

The rosters were loaded with Hall of Famers and stars, including Bob Feller, Warren Spahn, Stan Musial, Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Sandy Koufax, Roger Maris, and Whitey Ford. Frank Howard was an enormously popular invitee because the Washington fans still loved him.

“We got a call from the White House once asking if Vice President George Bush might be able to play first base,” recalled Cecil. “It didn’t work out, but we always had a lot of official Washington on hand—Tip O’Neill, Press Secretary Jim Brady, and many more.”

ALSO CHECK: Best Youth Baseball bat

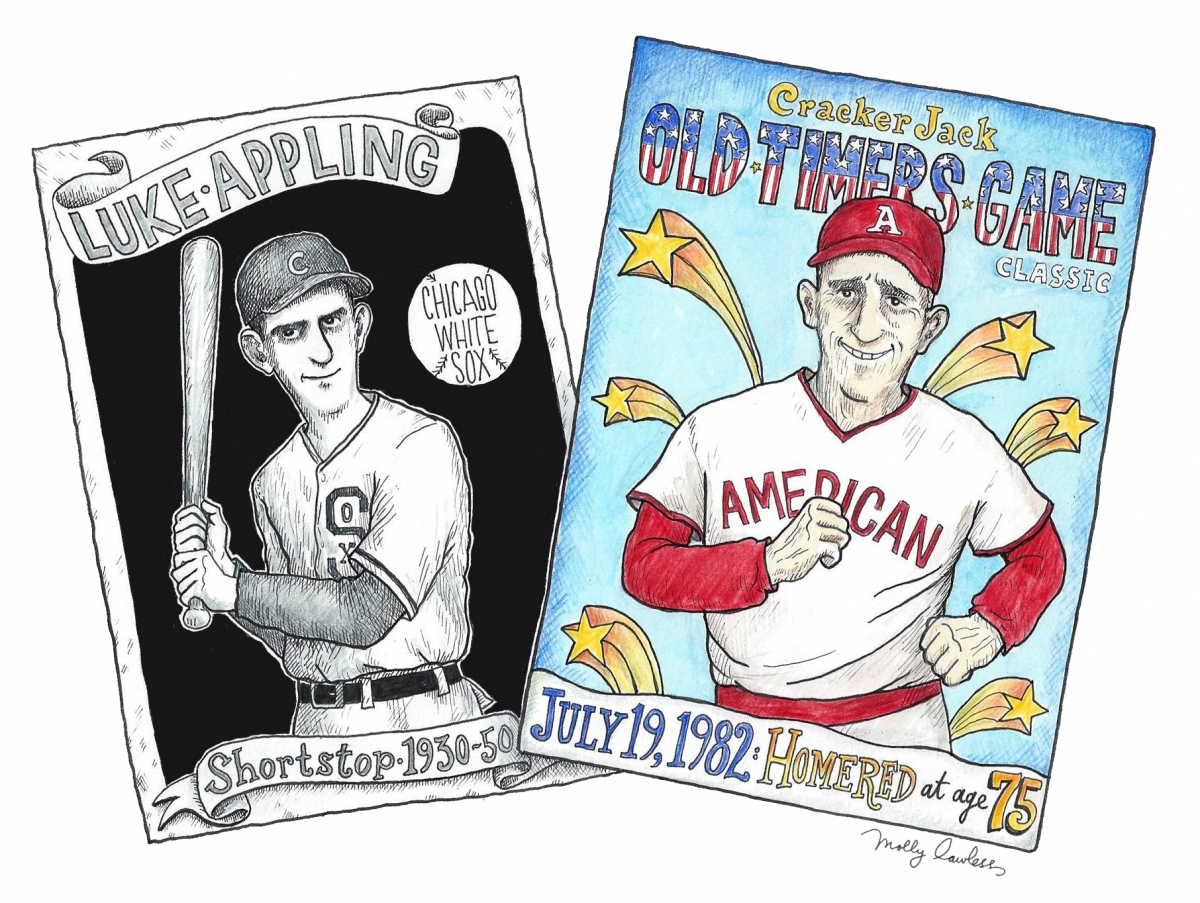

The game likely would have been a big hit locally, but it quickly got on the map nationally, when in the very first inning of the very first game on July 19, 1982, 75-year-old Luke Appling planted a Spahn delivery into the left-field stands.

“God bless Spahnie for that pitch,” said Cecil.

Appling, who only hit 45 homers in his 20-year career (1930–50), ambled around the bases to a fabulous fan reaction as players in both dugouts applauded. The left-field stands were somewhat drawn in—the mechanism to move the stands from a football layout to baseball had long ago rusted—but this was a big-time moment for Luke, for baseball, and for the Classic. Thanks to the ESPN coverage, it was played and replayed that very night on local newscasts around the country, and then again and again in the days that followed. It was not surprising that when Appling died in 1991, the home run was first-paragraph worthy in his obituaries.

After six years in Washington, the event moved to Buffalo, where the Rich family was anxious to show off their new ballpark, Pilot Field, to a national audience. ESPN was still aboard, but Tal Smith was called to New York for an arbitration hearing, and I was asked to manage the National Leaguers in what would prove to be the final game of the series.

What a moment this was for me. I was going to get to play Strat-O-Matic baseball with real players. Gene Mauch was to be my starting second baseman, and I told him, “Don’t be shy with suggestions—you’ve been doing this a lot longer than I have.” (He had managed 2,258 games to my one.)

By pre-arrangement, Koufax would be my starting pitcher, and with the arthritis that had ended his career in 1966 still bothersome, he said he’d like to throw one pitch and then come out. I talked him into one batter, not one pitch, and the batter would be Dick McAuliffe, the former Detroit Tigers star.

As luck would have it, McAuliffe kept fouling off pitches until he was finally retired, and it was time for Sandy to depart. But, never one to miss a moment, and egged on by Tom Seaver who was seated next to me in the dugout, I actually went to the mound and said, “Sandy, I don’t like what I’m seeing here,” and I took the ball and motioned for Spahn to relieve him. How many times did Walter Alston take Koufax out in the first inning?

Sandy laughed, and we both laughed some more at breakfast the next day.

Meanwhile, as I had planned, after two innings I went to Mauch and told him that I was going to send Don Blasingame out to play second in the third inning.

“Pay attention, rook,” said Mauch. “I sent him out there last inning.”

So much for my having full control.

I was a good manager though. I sized up Bill Robinson as my outfielder in the best shape, and Tug McGraw as my most able pitcher. I saved them both for the final inning, and sure enough, Robinson caught two fly balls on the run, and McGraw got a save, and the Nationals won 3–0. I was 1–0, and retired.

“After nine years, the game had run its course,” said Cecil. “We had a great run, the players loved it, the fans loved it, and we thought we did a lot of things right. We made sure the players always returned to the field at the end to wave their caps to the fans and thank them for their support.”

Old timers games were becoming common in the early ’90s, as Equitable Life sponsored one in each ballpark. Some players were appearing in as many as 20 old timers days a year. The Cracker Jack Classic (Cracker Jack actually bowed out after the Washington years) was history. But what a special annual event it was, especially for baseball-hungry Washington fans.