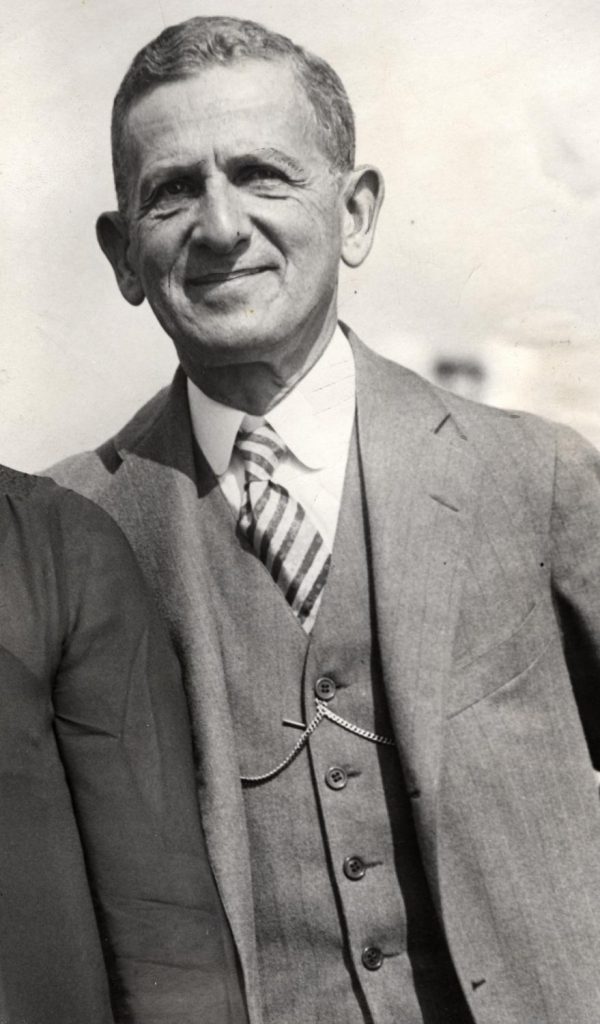

~Pittsburg Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss

On October 11, 1902, the closest thing to a World Series that year reached its anticlimactic finish. In front of 4,768 fans at Pittsburgh’s Exposition Field, Cy Young pitched a five-hit shutout to lead a team of American League All-Stars to victory over the National League–champion Pittsburgh Pirates. Pittsburgh had already clinched the four-game exhibition series by winning the first two games and tying the third, but they were obligated to play the fourth game, perhaps for the promise of gate receipts or to allow wagers to be settled.

Pittsburgh had gone 103–36 during the season, withstanding raids by the rival, upstart American League that took pitchers Jack Chesbro and Jesse Tannehill. But Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss was unfazed and wanted more, with the Democrat and Chronicle of Rochester, New York, reporting December 1, 1902, that Dreyfuss had bet $1,000 with a steel man that his team would win the 1903 pennant.

“I have made this bet, and I am willing to make it ten times as much before the season opens,” Dreyfuss said. “I particularly want to get some of the money hung up which the American League people have. They have made the crack that they have riddled the Pittsburg team. I want to know. They can win my money if they have the sand or put up the real coin. Now is their time to bet. I wager, and will go to the finish, that Pittsburg wins the pennant next season, that is, the coming season. Do I hear any response? I want to prove that the American League has not hurt Pittsburg’s ball team very much. The places of Tannehill and Chesbro are easily filled.”

A larger contest was coming, one where Dreyfuss would have to eat his words.

* * *

The idea was at least a year old when the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Boston Americans kicked off the first World Series on October 1, 1903. Maybe it had only recently become feasible, with American and National League owners agreeing that January in Cincinnati to end the war that had raged since the American League’s founding in 1901.

But even amidst the infighting, people like Dreyfuss could dream. The Pirates won the National League pennant in 1901. In June 1902, when they already looked on their way to a repeat, Dreyfuss spoke to the Evening Star of Washington, D.C. “I’ll tell you what I’ll do,” Dreyfuss said. “I will wager $5,000 on a series of ten games between the Pittsburg team, if it wins the pennant, and the winner of the American League championship. We will play the winning team, or a picked team, but probably a regular team would play better ball. I think ten games would be a fair number to play, five games to each city.”

The Evening Star reached out to Philadelphia Athletics Manager Connie Mack, whose team would go on to take the American League pennant in a close race.

“Barney is one of the nicest fellows in the business and one of the very few magnates connected with the National League that possesses the slightest remnant of the true spirit of sportsmanship,” Mack said.

“Has a splendid team. It is really a shame that it is not a member of the major league. On the level, I think it would have a fighting chance to break into the first division in the American League. But when he talks about betting $5,000 that it could beat the winner of the American League pennant, he talks a good deal like a crow performs its ablutions—at random. The fact that he has everything beaten way off in the National League has affected his vision. He is looking through the inverted end of the looking glass.”

But Mack didn’t rule out a postseason series, saying, “We’re going to be �?thar or tharabouts’ at the finish, but whether we win the flag or not, there is nothing that would give me more genuine pleasure than playing a series of games with Pittsburg, as Mr. Dreyfuss suggests.”

It didn’t happen, though in early February 1903, the Evening Star reported Mack challenging Dreyfuss to a series of exhibition games that spring. Dreyfuss initially refused, but he thought better of it.

“I have already prepared for the Pittsburg team to go away to Hot Springs, Arkansas, for spring training,” he told the Courier-Journal of Louisville, Kentucky, on February 12. “Then, too, we have our schedule of preliminary games all made out to April 14. To make it worth while to change these plans, I will be willing for Pittsburg to play the Philadelphia Athletics for a series of games for $5,000 a side and the entire gate receipts. The spring is not the time to play such an important series, but I am willing to take the risk of injury to players.”

The Courier-Journal billed the games as being for the “world’s championship.” The paper also quoted Mack, who said that he wouldn’t be comfortable with the winner taking all receipts, “but if Mr. Dreyfuss is really anxious to meet us I can assure him that he will be accommodated if he meets us half way. My principal reason for wishing to play the Pittsburgs is to show the public that the Athletics are really a champion team, and that the pennant was not won by a fluke.”

No mention of the series ever coming off could be found via newspapers.com, where all clippings for this article were located, though the series appears unlikely to have occurred. Soon after their remarks in the press, Dreyfuss took his team to Hot Springs while Mack accompanied his to Jacksonville, Florida.

On July 28, 1903, with the Pirates in a fight for their third straight pennant and the American League race also close, Dreyfuss again made the pitch for an interleague series.

“If Pittsburg wins the National League pennant, as I believe she will, Pittsburg will challenge the winner of the American League pennant to a series of 11 games to decide the championship of the world,” Dreyfuss told the Cincinnati Enquirer. “The question of baseball supremacy must be settled. We did not play Philadelphia last year for reasons best known to the Philadelphia League management. We played the cream of the American League, and beat this constellation decisively. There is still a disposition to dispute Pittsburg’s championship last year. Connie Mack yet claims he could have beaten us. Let us have no dispute at the end of this season.”

Dreyfuss laid out four conditions: that the winning club receive 75 percent of gate receipts, with players not to share; that all 11 games be played even if one team won all of them; that there be two umpires per game, one chosen by each team; and that the winning team tour the West as champions of the world.

Boston Americans player-manager and future Hall of Famer Jimmy Collins accepted the challenge, telling the Pittsburgh Press on July 30, “Our boys deserve the greatest prize in the world for the fine exhibition they have put up this season, and that with such players as Charley Farrell and Chick Stahl out of the game most of the time.”

Still, the deal was far from set. Dreyfuss and Boston Americans owner Henry Killilea were reported to soon meet after a league meeting in Buffalo in August where a new national agreement between the leagues was forged. Killilea served on the American League committee at the meeting, though Dreyfuss reportedly missed it because a telegram requesting his presence arrived too late.

In early September, Dreyfuss and Killilea struck a preliminary agreement for the postseason series, though it soon threatened to unravel. Killilea wanted to keep all of Boston’s share of the gate receipts and simply extend the contracts of his players, due to expire September 30, to October 15. Boston players balked, hearing that Dreyfuss had agreed to give his players half the receipts as well as their normal salaries. They initially threatened to back out of the Series, with John McGraw offering to sub in his second-place Giants.

American League President Ban Johnson made plans to travel to town to personally intervene. But the dispute was resolved before he could arrive, with Killilea, who was based in Milwaukee, and team Business Manager Joseph H. Smart, who ran day-to-day operations, talking by phone after a game. Boston’s players settled on 75 percent of the team’s receipts and, presumably, no salary extension.

Boston would go on to win the inaugural World Series, five games to three, taking advantage of a depleted Pirates pitching staff that badly needed Chesbro and Tannehill, as well as injured Sam Leever and Ed Doheny, who suffered a nervous breakdown during the season and had to be institutionalized. Sporting Life reported on October 24, 1903, that Boston players received $1,182, “just what was coming to them and not a penny more.” Killilea, who would sell his team months later, received $6,699.56.

Dreyfuss gave his share of receipts to his players and also paid them their normal salaries, with sporting Life estimating each player walked away with at least $1,500. In addition, Dreyfuss gave 10 shares of stock to pitcher Deacon Phillippe, who started five games and pitched 44 innings in the Series, records that still stand.

Dreyfuss’s efforts haven’t been forgotten. In 2008, he finally earned a place in the Hall of Fame.