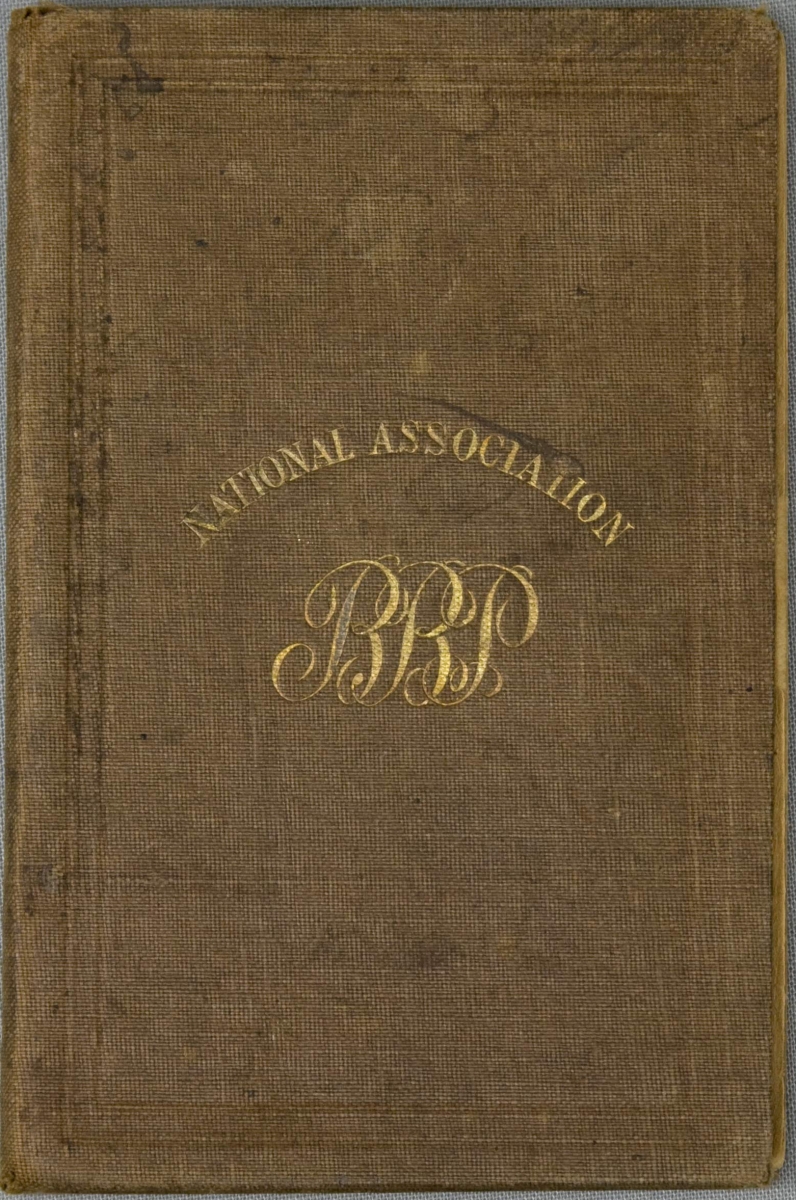

Major and minor are relative terms; something is major or minor based upon its relative position among a group of objects. In the United States, the Democrats and Republicans are considered major parties, while the Libertarians and Greens are minor parties. If the former two didn’t exist, the Greens and Libertarians would be the major parties, even if they were no more significant than they are now. Since the National Association (NA) was the only baseball league in existence from 1871 through 1875, how could it not be considered a major league?

That question was answered by the Major League Special Baseball Records Committee, assembled in 1968 by then-Commissioner William Eckert, which stated that the NA was not a major league “due to its erratic schedule and procedures.” Scheduling and procedures are reflective of the management of the sport rather than the quality of play on the field, and if inept administration can disqualify a league from major status, perhaps the records of the American and National Leagues during Eckert’s sorry tenure should be expunged. We can stick Denny McLain’s 31 wins and Bob Gibson’s 1.12 ERA in the same trashcan with Levi Meyerle’s .492 batting average in 1871 and Al Spalding’s 54–5 pitching record in 1875.

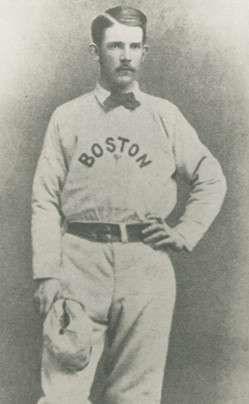

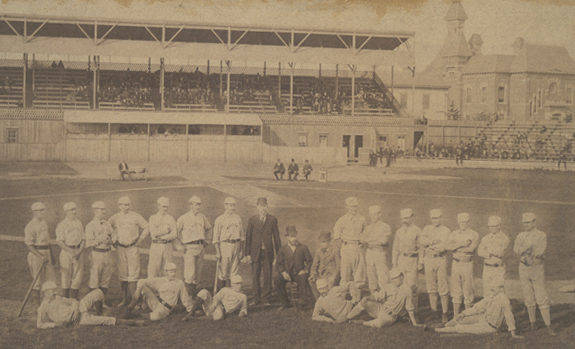

The primary criterion for defining the quality of a league should be the relative skill of its players in relation to that of all players active at that time. There is no question that during the first half of the 1870s the best baseball players in America played in the National Association. There were a few professional teams that were not members of the NA, but they were clearly of inferior caliber, and it was a major upset when one of them beat an NA team. None of the amateur teams was remotely as good as the professionals, and when NA teams went on tour to play amateurs and lesser professionals, they often won by scores such as 20–2 or 35–4, and sometimes much more. Anyone who was serious about playing baseball for a living wanted to play in the NA.

If the NA is not considered a major league, there is certainly a strong case that neither was the National League of the late 1870s. The National League (NL) survived and got to write the history, but contemporary accounts show that it was not the dominant baseball organization portrayed in the history books. From 1877 through 1880, a number of strong professional teams that were not members of the NL operated under a loose organization first known as the International Association (IA) and then, after the Canadian teams had withdrawn, as the National Association. Although the IA and NA have never been given serious consideration as major leagues, their teams often played exhibitions against NL teams, and the games were not the one-sided mismatches that usually occurred when the old NA clubs faced outside opposition. In 1877, IA teams beat NL teams on 72 occasions, according to the New York Clipper, and on September 28, 1878, the Clipper reported that for the season the IA was 21–33 against NL competition. Buffalo and Cleveland of the IA were each 5–3 against NL teams.

The reason IA and NA teams could play competitively with NL clubs was that not all of the best players wanted to be in the NL; several top players asked to be released from an NL team to play with an NA club. Salary information is limited, but it does not appear that there was a great discrepancy in pay between the two leagues, certainly not the difference between major and minor league salaries of today. Some players chose the NA because they wanted to stay close to home, while others didn’t like the strict regimentation of William Hulbert’s league.

Another criterion for major league status might be the presence of franchises in America’s leadingcities. No one took the National Football League seriously when it had teams in Rock Island, Rochester, and Racine. From 1877 through 1882, the NL was absent from New York and Philadelphia, the two largest cities in the United States, and had teams in secondary markets like Troy, Syracuse, Providence, and Worcester. The old NA (the one not considered a major league) had teams in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston for its entire existence, and one in Chicago for all but the two years following the Great Fire.

If erratic scheduling can disqualify a league from major status, it must be noted that the NL did not have a formal schedule in 1876, and two of its teams, the Athletics and Mutuals, were expelled for failing to complete their quota of games. In 1877, the league voted to throw out the Cincinnati games because of unpaid dues. During the 1879 season, Syracuse folded in early September, and each year there was turnover as teams dropped out and new entries enlisted.

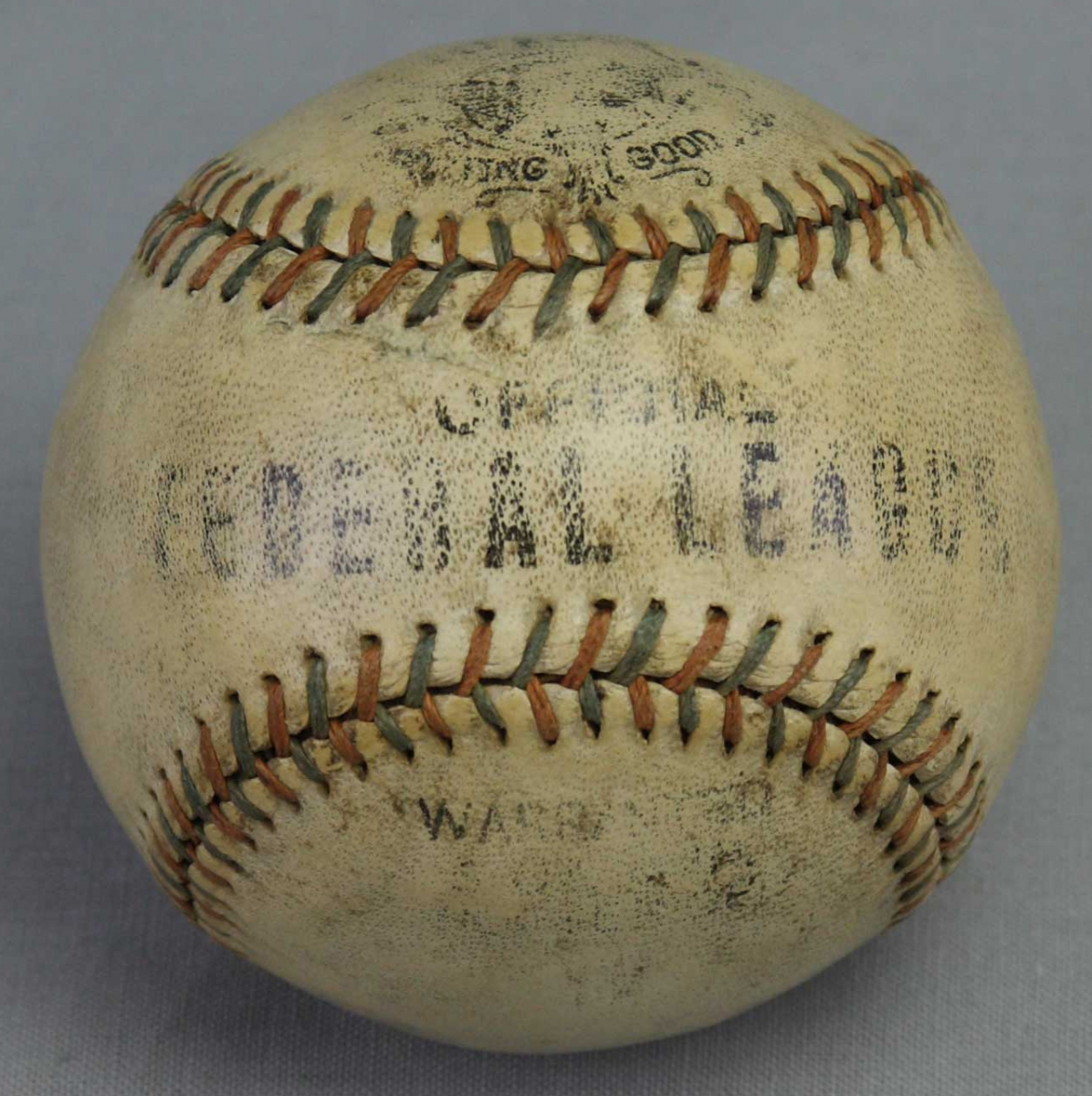

The Players’ League, the Union Association (UA), and the Federal League, each of which existed for only one or two years, were determined to be major leagues by the Special Records Committee. The Players’ League is the only one of the three that can claim to have employed the best baseball players in the country. The Federal League had a few big names, but their rosters were largely populated by aging NL or AL veterans, minor leaguers, and second-tier players whose “major league” careers ended with the demise of the Federal League. Outfielder Benny Kauff, the Feds’ biggest star, was later signed by the Giants and was never more than an average National League player. George McConnell, who led the Federal League with 25 pitching victories in its final season, won four games for the Cubs in 1916 and then disappeared from the Major Leagues for good.

The Union Association has the weakest claim on major league status, being the third best league in a year where the “major leagues” expanded from 16 teams to 33 and from 282 players to 546. With the number of players nearly doubling, there was a severe dilution of talent, and the Union Association was the league at the bottom of the totem pole, getting the slimmest pickings. There was only one good UA team, the St. Louis franchise owned by league president Henry Lucas, which ran away from the field and rendered most of the season rather uninteresting. Some teams folded and others were moved in midseason.

Popular Posts

Best Youth Baseball Bats

Best BBCOR Bats

Best USA bats

Best Softball Bats

Best Wood Bats

Like the Federal League, the UA had a few stars, augmented by a lot of roster fillers who never played in the NL or American Association (AA) before or after. The UA did not recognize the reserve clause and thus, was at war with the other two leagues, which refused to play exhibitions with them, so there was no direct competition. It is safe to say, however, that other than St. Louis the UA teams were far inferior to NL or AA clubs.

If we consider the old NA a major league due to its exclusivity, must we say the same of the old National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP), which governed baseball from 1858 through 1870? The best players in America played for teams under the auspices of the NABBP, and it, like the NA, was the only game in town. The NABBP, however, made no pretense of being a league; it was a governing body without a formal method of determining a champion, and in its final years it presided loosely over an amalgamation of professional and amateur clubs. It was neither a major nor minor league; it was simply not a league.

The Special Records Committee, while not granting the NA major league status, explicitly stated that “it will continue to be recognized as the first professional baseball league.” If the committee acknowledged that the NA was a league, and it was the only league, must it not, therefore, have been a major league? For when an organization consists of the best players in the country playing for franchises in its largest cities, the result is a major league.

The conditions and rules of the early 1870s were undeniably different than they are today, and Al Spalding’s 54 wins can’t be compared with the records of Sandy Koufax and Roger Clemens, but neither can records of players from the early twentieth century. Babe Ruth didn’t play against African-Americans or Latinos, he didn’t hit against scientifically contrived defensive shifts, and he didn’t face a succession of relief pitchers throwing close to 100 miles per hour, but no one talks of taking him out of the record books or calling the American League of the 1920s a minor league. Baseball is baseball, and the best league in baseball is a major league; maybe it’s time to acknowledge it.

Note: For information on the Special Records Committee, I am indebted to a post on ourgame.mlbblogs.com of May 4, 2015.