Nearly 45 years ago, five men made a decision that has colored our view of baseball history ever since. Collectively, they were known as Special Baseball Records Committee, and they were brought together because, with the imminent publication of the first edition of The Baseball Encyclopedia, “it became necessary to draw up a code of rules governing record-keeping procedures.”

According to Appendix B of that massive, wildly successful first encyclopedia, there were 17 issues the committee had to vote on. And the first was deciding which leagues would be treated as major and thus appear in the encyclopedia.

The committee chose six leagues for this exalted status. The National League (beginning in 1876) and the American League (1901) were easy. Not easy: the big-time American Association, which competed with the National League from 1882 through 1891. The AA was (and is) widely regarded as being inferior to the National League, but it had a lot of good players.

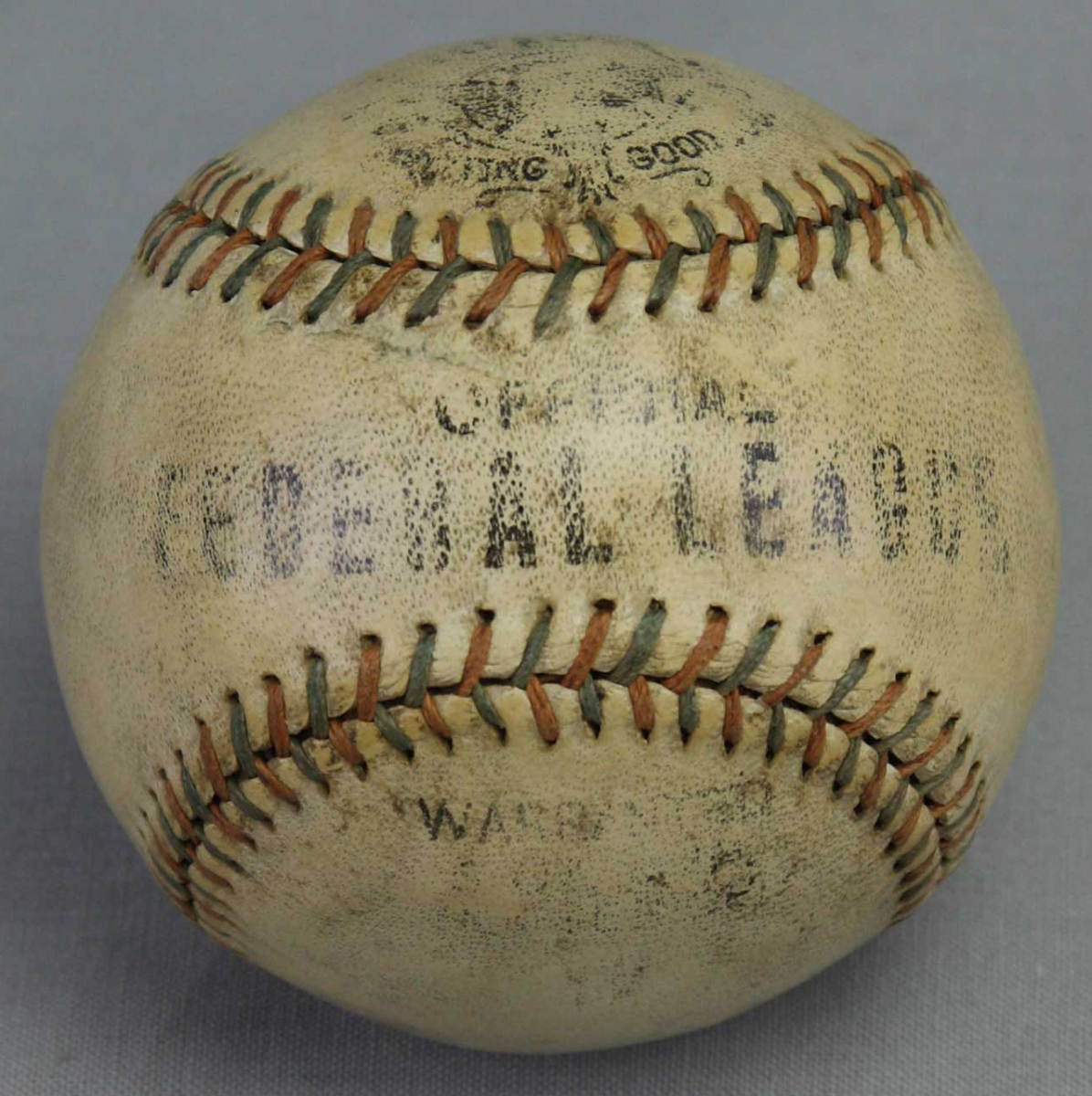

The other three supposed major leagues were terribly short-lived: the Union Association (1884) and the Players’ League (1890) lasted for just one season apiece and the Federal League for two (1914-1915).

Frankly, nobody talks much about the Union Association or the Players’ League, probably because few people care much about 19th century baseball. Who won the National League pennant in 1896? I know a lot of people who are crazy about baseball history. But while nearly all of them know the Chicago Cubs won the pennant in 1906, I’ll bet only two or three of know the NL’s original Baltimore Orioles took the flag in ’96.

The Federal League is different. By 1914, the inaugural season, modern playing rules were in place. The league’s teams played, for the most part, in cities that today host Major League franchises. They played 154-game schedules, just like the American and National leagues with which the Federal League was expressly designed to compete. Just last year, a fantastic book, The Battle That Forged Baseball: The Federal League Challenge and Its Legacy, was published.

Popular Posts

Best Youth Baseball Bats

Best BBCOR Bats

Best USA bats

Best Softball Bats

Best Wood Bats

We’ll probably have to wait a while for a similar treatise on the Union Association.

So did the Special Baseball Records Committee get it right? Was the Federal League really a Major League?

To answer that question, we have to come to some sort of agreement regarding what makes a Major League. I believe that Bill James once addressed this issue, and (because he’s Bill James) came up with a list of a dozen or more things we expect from a Major League. At the risk of omission, though, I’m not going to hunt for James’s list. Because, roughly speaking, I think we can agree that we’ve got a Major League if (a) there are teams playing a set and lengthy schedule, and (b) these teams are populated largely by the sport’s best players.

Ah, but how do we define “best players”?

That can be as tricky as we like, but in this case we’ve got an easy way to compare the players in the Federal League to those in the contemporary American and National leagues. The Federal League lasted for only two seasons. When the circuit folded, its players suddenly became available to the 16 clubs in the other big leagues. If the Federal League players were roughly on par with those in the American and National Leagues, we would expect somewhere between a third and a fourth of them to find jobs in the existing Major Leagues—assuming, of course, there was a completely free flow of talent.

But perhaps the flow wasn’t free. And perhaps AL and NL clubs didn’t see the point in replacing their scrubeenies with the Federal League’s scrubeenies.

So let’s instead look at the Federal League’s stars. If that league was legitimately Major, we would expect the Federal League’s stars to not only find homes in the Majors, we would expect them to maintain their status as stars. Or at least come close.

What actually happened to the Federal League’s stars? With the help of Baseball-Reference.com, I made a list of the 10 Federal Leaguers who compiled the most Wins Above Replacement (WAR) during the league’s two seasons.

Those 10 stars totaled 70 WAR over 1914 and ‘15. If they were on a par with the stars of the other Major Leagues, we might expect them to roughly approximate that number over the next two years. Oh, except we should assume some regression to the mean, and we might also guess that there was some prejudice against Federal League players. So let’s be exceptionally conservative, and instead guess that Federal League stars might be just half as valuable over the next two seasons: 35 Wins Above Replacement in 1916 and ‘17.

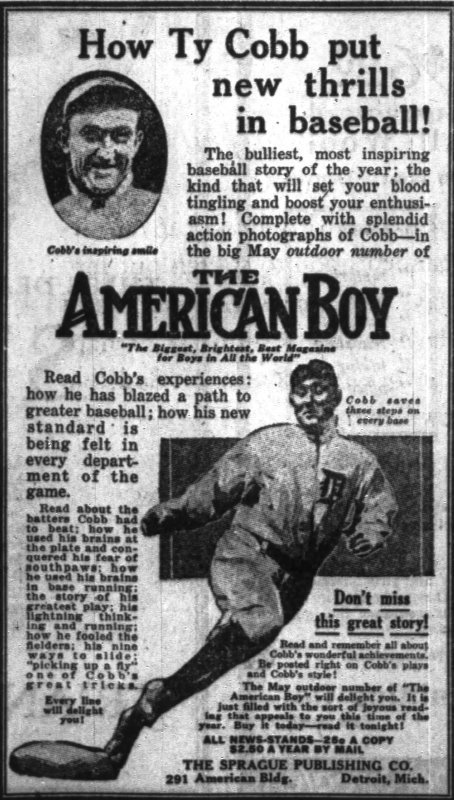

The actual figure was 8.4 WAR and nearly all of that was because of just one player, a questionable character named Benny Kauff. They called him “the Ty Cobb of the Federal League,” and he really did hit like Ty Cobb—as long as he was in the Federal League. In 1914 and ‘15, he batted .370 and .342, won batting titles, and also claimed stolen-base crowns with 75 and 55.

In 1916, still only 26 years old, Kauff joined the New York Giants. And though Kauff played well for the Giants, he was hardly great. After batting .357/.447/.523 in his two seasons with the Federal League’s Indianapolis Hoosiers and Brooklyn Tip-Tops, Kauff fell to just .286/.364/.398 in his first two seasons with the Giants.

Sure, Kauff was facing tougher pitchers, but that’s sort of the point. He was the Federal League’s best player by a lot. After which, he became merely a good player in the National League.

Of course, bad things do happen to good players. We need some basis for comparison. So I ran the same study for the American and National leagues. And to be sure, the stars were better in years one and two than in years three and four for various reasons.

In 1915 (year two), Honus Wagner still ranked as one of the NL’s biggest stars at age 41. Two years later, he hardly played. Cubs outfielder Vic Saier played brilliantly in 1914 and ‘15. But he suffered a debilitating leg injury in the second half of the ‘15 season and missed nearly all of the ‘17 season with a broken leg.

In baseball, bad things happen to good players. But even with those bad things, the real Major League stars of 1914 and ‘15 generally played quite well in 1916 and ‘17, too.

• In years one and two, the top American Leaguers totaled 106 Wins Above Replacement; in years three and four, they dropped to 79 WAR.

• In years one and two, the top National Leaguers totaled 85 Wins Above Replacement; in years three and four, they dropped to 69 WAR.

It was a 26 percent drop for the American Leaguers and 19 percent for the National Leaguers. And the Federal League stars? Their Wins Above Replacement dropped 88 percent. And without Kauff it would have been 99.6 percent.

There are a hundred other ways to compare the talent in the Federal League to that in the other leagues, but we would always come up with the same answer: the best of the Federal League players, with the exception of Kauff, were barely good enough to play in the real Major Leagues at all.

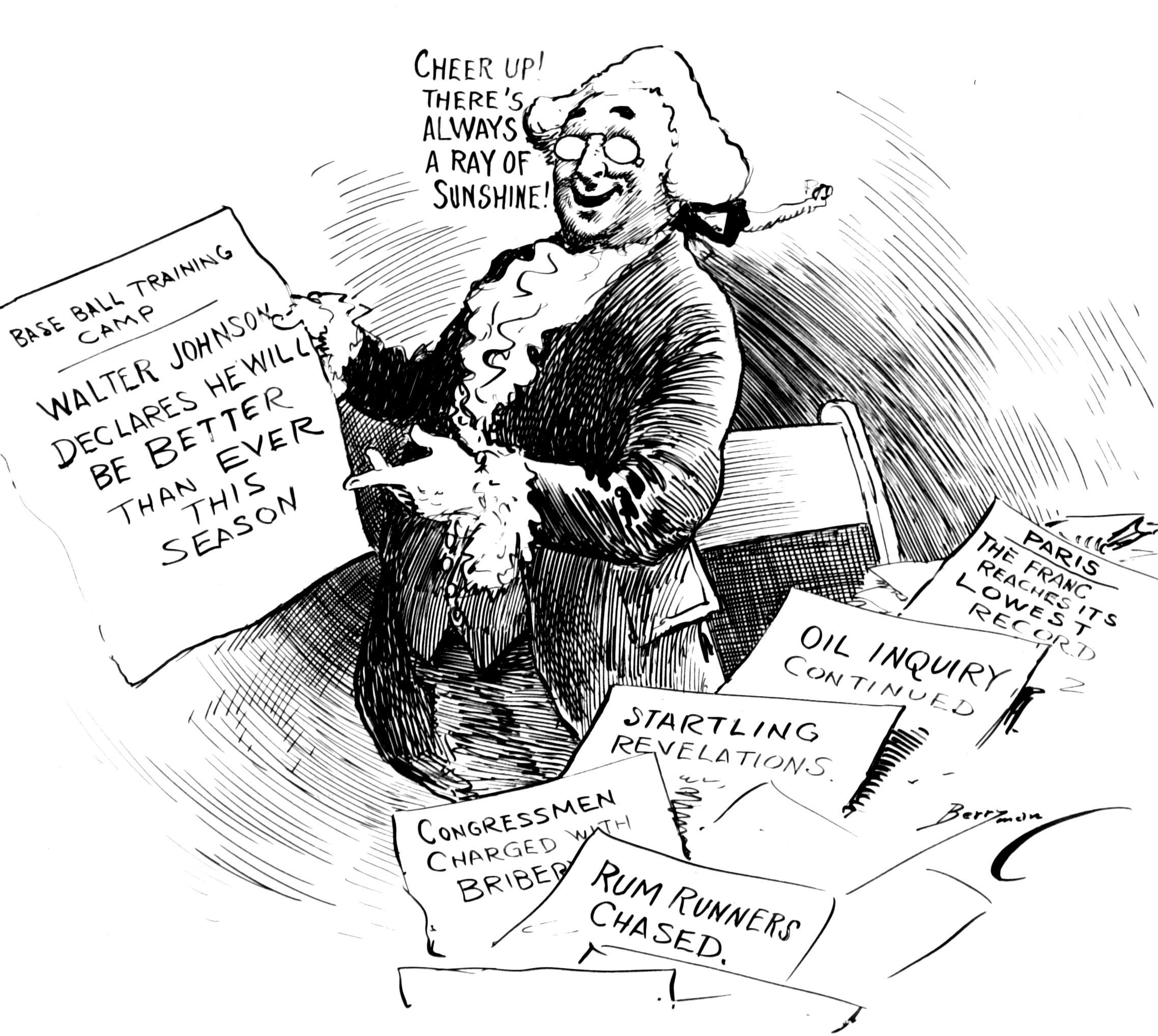

The Federal League’s inability to attract baseball’s biggest stars wasn’t for lack of trying. The Feds offered significant financial inducements to a number of top players, some of whom actually accepted those offers. Washington’s Walter Johnson, the game’s greatest pitcher, signed a three-year contract with Chicago’s Federal League club. But, as happened in a number of other cases, Johnson was lured back to the Senators by a combination of financial blandishments and psychological pressure. In the end, what few stars the Federal League did boast—Joe Tinker, and pitchers Eddie Plank, Chief Bender, and Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown—were well past their primes and did little to win games or attract fans.

All four of those ex-stars would eventually be elected to the Hall of Fame. But just one Federal Leaguer would make it, and that is because of what he did after his Fed career. Edd Roush played briefly for the Chicago White Sox in 1913, then joined the Federal League’s Indianapolis franchise in 1914. When that club moved to Newark in 1915, Roush went with it. And when the Federal League folded, the New York Giants purchased the rights to Roush’s contract. Halfway through the ‘16 season, a struggling Roush was traded to the Reds, with whom he became a big star and won a couple of batting titles.

Roush wasn’t the Federal League’s only legacy. Charles Weeghman built a ballpark for his Federal League team in Chicago and called it Weeghman Park. When the Federals folded, Weeghman took control of the National League’s Chicago Cubs and moved his new team into his ballpark. That ballpark would eventually become known as Wrigley Field and, of course, the Cubs still play there.

In 1922, a lawsuit filed back in 1916 by the Federal League’s Baltimore franchise wound up in the United States Supreme Court. In its ruling against Baltimore, the Supreme Court established that organized baseball was not commerce, and thus not interstate commerce, and thus not subject to the antitrust provisions of the Sherman Act. This would have, and still has, far-ranging impact on Major League Baseball’s ability to essentially operate as a monopoly.

That is perhaps the Federal League’s biggest legacy. But we must also consider the legacy created by the Special Baseball Records Committee. Ever since 1969, with the publication of The Baseball Encyclopedia, the Federal League has been treated in the record books as a Major League, right alongside its two 20th-century counterparts. In all the encyclopedias since, both in print and on the Web, unsuspecting baseball fans have been led to believe that the Federal League was roughly on par with the American League and the National League.

So how and why did the Records Committee come to this conclusion?

Well, there was a precedent for it. During the league’s existence, Francis Richter’s Official American League Base Ball Guide—which covered all of organized baseball, along with the Federal League—seemed to take the league at its word. In the 1916 guide, Richter (or one of his underlings) even wrote, “No better ball was furnished by any league anywhere, or at any time.”

In 1940, The Sporting News began publishing the annual Baseball Register. For some years, the Register included the records of a few old-time stars. And when someone had played in the Federal League, those stats were included in his Major League totals.

So one might excuse the Records Committee for simply bowing to the convention. I don’t. Its job was to collect evidence, weigh that evidence, and make some difficult decisions. In this case, either the members didn’t collect and weigh the evidence or they did but ignored it. Either way, I cannot excuse them.

Today there is no panel charged with these matters. The Baseball Encyclopedia no longer exists, nor are there any other records that come with Major League Baseball’s exclusive imprimatur. Nothing is official. But someone somewhere should strike a blow for common sense and strike everything that happened in the Federal League from the Major League records. This was a major league only on paper. On the field, it was but a pale imitation.