“Baseball is a legitimate profession. It should be taken seriously by the colored player. An honest effort of his great ability will open the avenue in the near future wherein he may walk hand in hand with the opposite race in the greatest of all American games—baseball.”

Sol White, 1907, from his History of Colored Base Ball

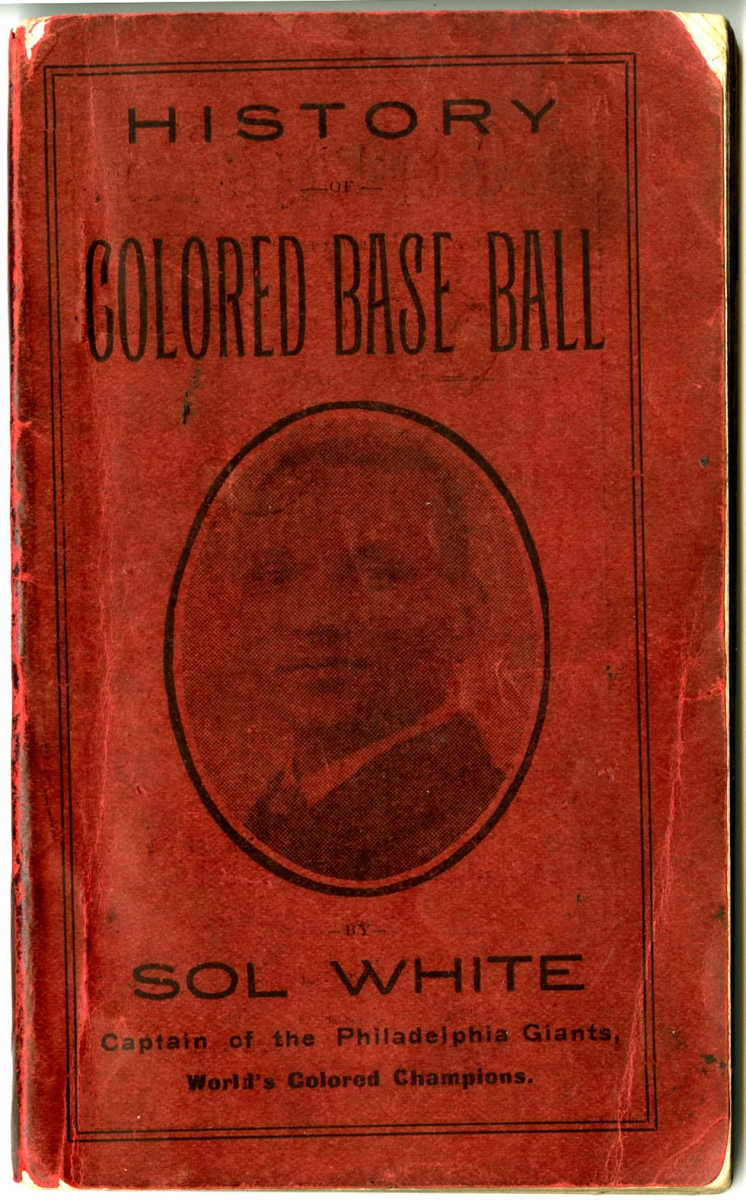

Directly after the turn of the 20th century, the History of Colored Base Ball was written by African-American ballplayer, manager, organizer, and promoter of the Negro Leagues, Sol White, a man who felt the sting of baseball’s barrier up close and personal when his own rising career on the diamond was stopped cold by the very same discrimination chronicled in his book. Though, as often happens in life, things thought impossible at one time actually travel full circle. In 2006, a century after publication of his remarkable book and almost 120 years after Sol’s own career was abruptly ended because of baseball’s notorious “color barrier,” Sol White was inducted into the shrine dedicated to preserving the memory of the greatest ballplayers of the National Pastime, the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

A Baseball Career Begins

King Solomon “Sol” White was born June 12, 1868 in Bellaire, Ohio, merely three years after the Civil War ended, but smack in the middle of baseball’s explosion in popularity. As a sports-minded 15-year-old, Sol haunted the baseball diamonds in his hometown and later a few miles away in Wheeling, West Virginia. Records indicate that he first began to play regularly with the Bellaire Globes, a top amateur team of the region. Sol’s team was integrated, a fairly common occurrence in areas throughout rural America for the first few decades after the Civil War. Sol played nearly every position on the field, but became mostly adept as a reliable contact hitter who could be counted on to hit in the clutch. Soon he became a team leader and was admired by all, including his white teammates.1

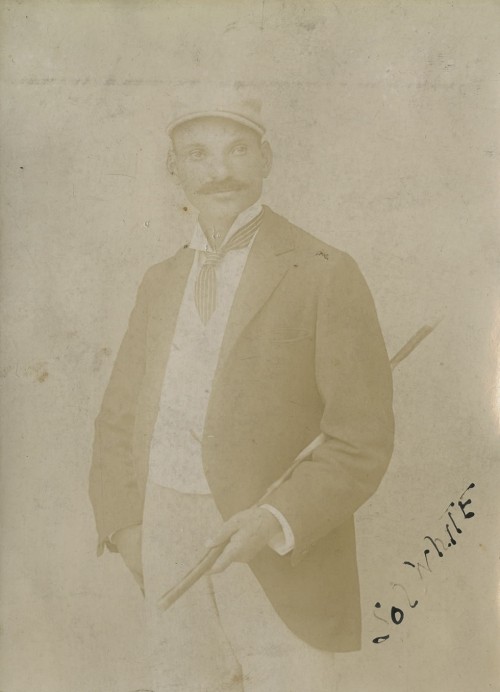

In June of 1887, 19-year-old Sol set his sights across the Ohio River in Wheeling where the caliber of ballplaying was fairly sophisticated. The professional Wheeling Green Stockings ball club, led by Sol’s friend and former Globes teammate, T. M. “Parson” Nicholson, recruited Sol to play third base. As the season closed, Sol hit at a torrid pace, finishing with a .381 batting average. Clearly, this was a notable debut for the rising star as Sol distinguished himself on a team that boasted some outstanding talent. In fact, several of his white teammates went on to have distinguished careers in the Major Leagues.

By the mid-1880s, Sol’s presence on a white team, in a predominantly white league, was nowhere near as problematic as it would soon become. Indeed, great black ballplayers like John “Bud” Fowler, George Stovey, Frank Grant, Jack Frye, and Robert Higgins all played regularly in barnstorming and white professional leagues. But, unfortunately, things would quickly and abruptly change.

The Color Barrier Comes Crashing Down

Against this backdrop, Sol’s talents as a ballplayer clearly blossomed and his baseball future seemed, at the very least, hopeful. But the reality of the times proved disastrous for all black ballplayers just as Sol was making his mark. Imagine how life was for Sol and other African Americans, as it was only seven years later that the United States Supreme Court put its stamp of approval on the separation of the races when it ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that “separate but equal” was not only constitutional but was an accepted and perfectly legitimate part of American life.

Baseball’s own discrimination was starkly revealed when Cap Anson—perhaps the most popular baseball player of the 19th century—refused to play against a Newark team for reasons that went to the heart of the matter. Why did Anson refuse to play baseball, the game he virtually represented, at the time? Well, Newark boasted not one, but two, African Americans. Fleetwood Walker and George Stovey played on the all-white Newark Eastern League team. No sooner than Anson had threatened to walk, the “color barrier” came crashing down with stunning quickness all across the nation.

After the “Anson episode,” Sol returned to the Keystones, then in 1889 traveled to New York City where he played for the Gorhams. Throughout the 1890s, he played ball when he could, studied theology at Wilberforce University in Ohio, and by the turn of the century, kept his love of the game alive by barnstorming for several games with the Chicago Columbia Giants, a team of excellent ballplayers who for years traveled extensively and were formerly known as the Page Fence Giants.

In 1901, Sol partnered with H. Walter Schlichter, a white sportswriter from Philadelphia and began, in earnest, the role that he is most noted for today—not only as a player but primarily a historian, writer, and tireless promoter of black baseball. For the next decade, he not only played part-time for Mr. Schlichter’s newly formed Philadelphia Giants, but he managed the team as well. Also, significantly, he gathered material for what would become his most notable achievement: in 1907 he authored the book simply titled History of Colored Base Ball.

Sol White’s History of Colored Base Ball

The book itself is extraordinary. It not only reviews details of most major black baseball clubs that mushroomed across the land from the mid-1880s until the early 1900s, but it is jam-packed with statistics, league standings, and even photos of many black ballplayers. Today, we relish Mr. White’s foresight by including portraits of black ballplaying pioneers because they are the only images known to exist for many. The content of the book is also noteworthy because it was written only a few years after baseball’s color barrier became “the law of the land.” Mr. White, as black baseball’s first historian, not only met that aspect of the National Pastime head on but also did not mince words.

Popular Posts

Best Youth Baseball Bats

Best BBCOR Bats

Best USA bats

Best Softball Bats

Best Wood Bats

Sol wrote about Cap Anson and described the “venom and hate” as well as his “strenuous and fruitful opposition” to blacks gaining admittance to the Major Leagues. How bittersweet it must have been for White, almost 20 years after his own blossoming career was cut short, to write that Anson’s deed “hastened the exclusion of the black man from the white leagues.” That stain on the game, which haunted Major League Baseball for decades, effectively eliminated a chance for Sol and countless others to progress onto a big league baseball diamond. White passed away in 1955, ironically the very year that Jackie Robinson, Major League Baseball’s first black player since Sol was excluded, led the Brooklyn Dodgers to a World Championship.

After publishing his book, Sol’s ballplaying exploits on the diamond became a thing of the past. However, baseball was always in his blood, and he kept organizing teams and promoting the game well into the 1930s. And, of course, he enjoyed writing about the National Pastime on every occasion that he could. On March 12, 1927, Floyd J. Calvin, a columnist for the Pittsburgh Courier wrote a major piece on Sol. By then, he was known as the “Grand Old Man of Black Baseball” and Calvin noted something that answered a question that one might today logically ask: Why would a man, who was prevented from showcasing his considerable ballplaying talents, write—when no one else would—about black baseball? “His object in telling his story,” Calvin wrote, “. . . is to let some of the younger fellows know something of what was behind them—something of the struggles that have made possible the improved conditions of the present.” Sound familiar?

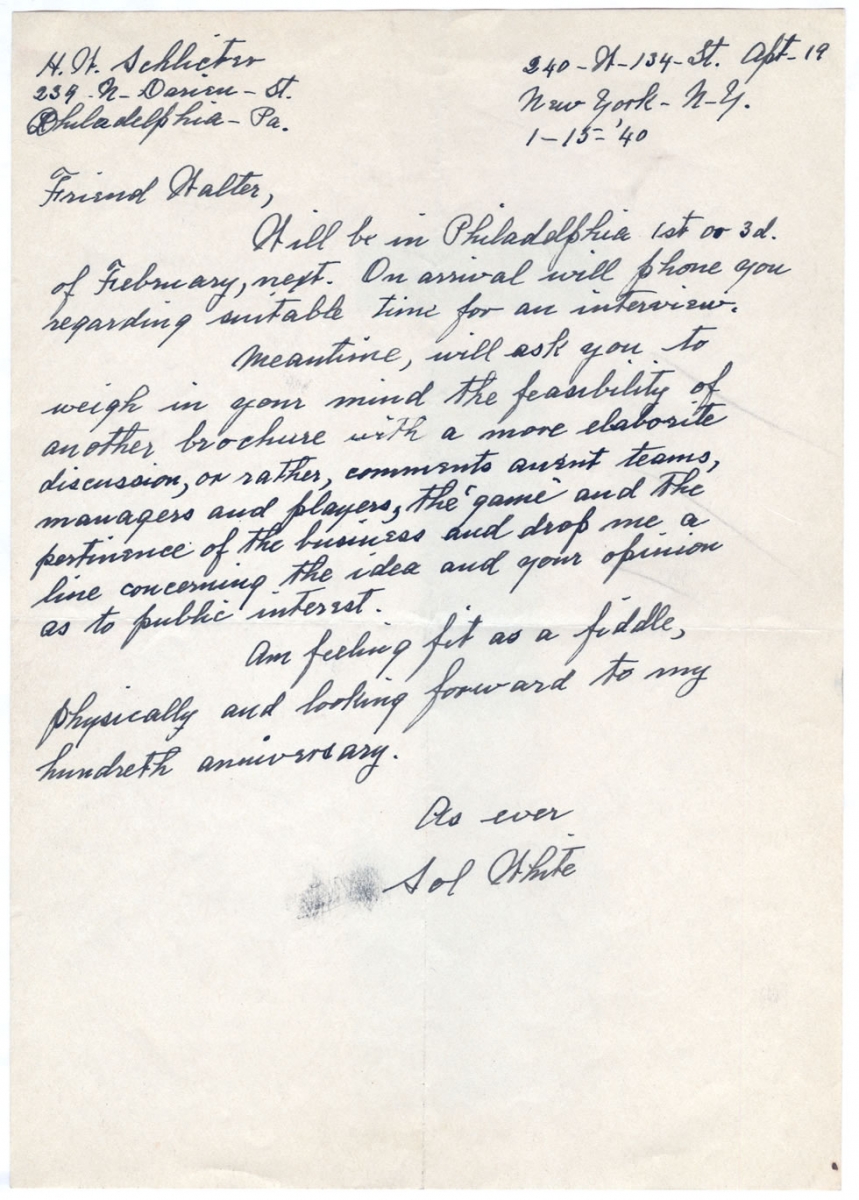

As the years rolled on, Sol took odd jobs in and around his home in Harlem, and it is said that he loved to spend his leisure time by visiting his local library. Occasionally, he would contribute something to the black press about baseball and even seriously considered updating his book or possibly writing another one. Our collection contains an extraordinary letter from 1940, the only handwritten letter of Sol’s known to exist. In it, he wrote to Walter Schlichter with his idea, specifically asking the former owner of the Philadelphia Giants to consider the “feasibility” of his writing a new historical “brochure.”2

Alas, for whatever reason, Sol White never did write his second “history” book. Having read the nuggets of information from his 1907 book, we can only imagine how Sol would have added to the depth of our knowledge if he would have written about the heyday of the Negro Leagues from the early 1920s until the late 1940s. Sol married at some point,3 but the couple separated, and to our knowledge, they had no children. Mr. White himself succumbed in 1955 at the age of 87 while staying in a state hospital in Central Islap, New York. Today he is buried in an unmarked grave in Frederick Douglass Cemetery in the Oakwood neighborhood of Staten Island, New York. On his death certificate, King Solomon White’s occupation is listed simply as “an elevator operator.”

How rare is Sol White’s book? Today, precious few of White’s “guides” have survived. After all, they are over 100 years old and even during Sol’s own time, they were exceedingly rare. Indeed, during his later years, Sol disclosed that even he did not possess a copy. To our knowledge, only five or so copies presently exist, either in private hands or research libraries. Ours is a classic “attic find” that came to us last year. Believe it or not, the owner had never bothered to open the book until they called us. The family was literally about to take Sol’s book to a used bookstore in a box of old books when she decided to give us a call. She was set to charge $50 for the entire box! We are certainly grateful that she did call us so that you can enjoy learning about King Solomon White and his 1907 National Treasure!

1Interestingly, as a member of Globes, Sol and his teammates played against a scrappy team of white ballplayers from Marietta, a nearby town, captained by Ban Johnson. Johnson, of course, would later become the first president of the American League. In 1927, in fact, the Pittsburgh Courier noted that “Sol takes pride in having played against Ban when the American League president was an obscure captain of a hick town club.”