Today’s age of Sabermetrics is bringing us a stream of more and more complicated statistics that measure more and more intricate aspects of baseball. In the wake of “Moneyball,” on-base percentage became the favored stat for estimating a player’s actual worth, but we’re moving toward OPS+ (on-base percentage plus slugging percentage, adjusted for home field and other factors) as the “best” stat for evaluating hitters. It’s easy to forget a much simpler time populated by bare stats untrammeled by analysis. But those bare stats can tell us all we need to know about certain players.

The earliest box scores contained only two pieces of information: outs and runs. That’s all that really counts in baseball; the rest is detail. Outs hurt your team, and runs determine who wins. Picture today’s elaborate cyberspace box scores, with all that data about how many runners each batter left on base, who threw how many pitches, how many ground ball outs each pitcher got compared to fly ball outs and all the rest of it — but with no information about runs. You know everything except what counted.

Also Check: Origin of art of pitching in the 19th Century

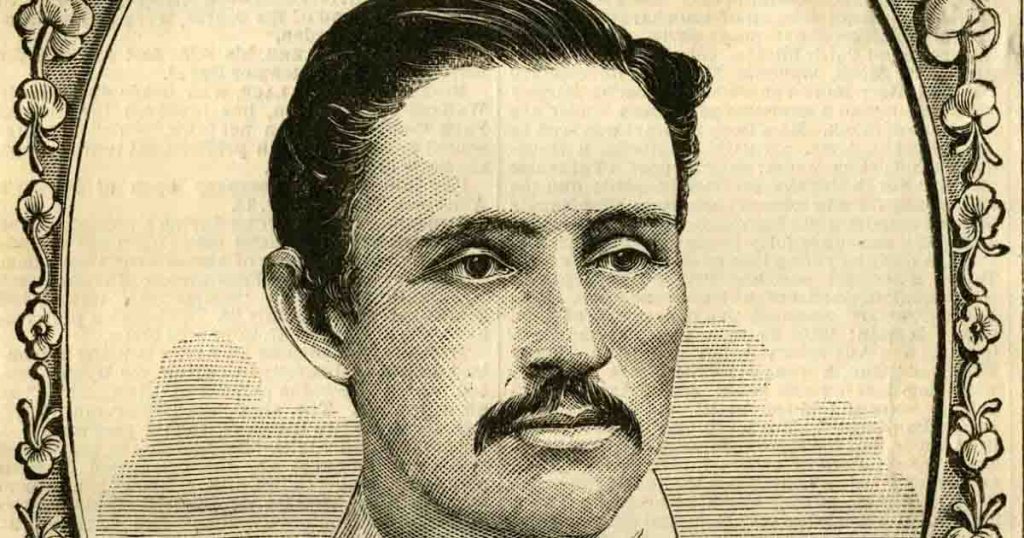

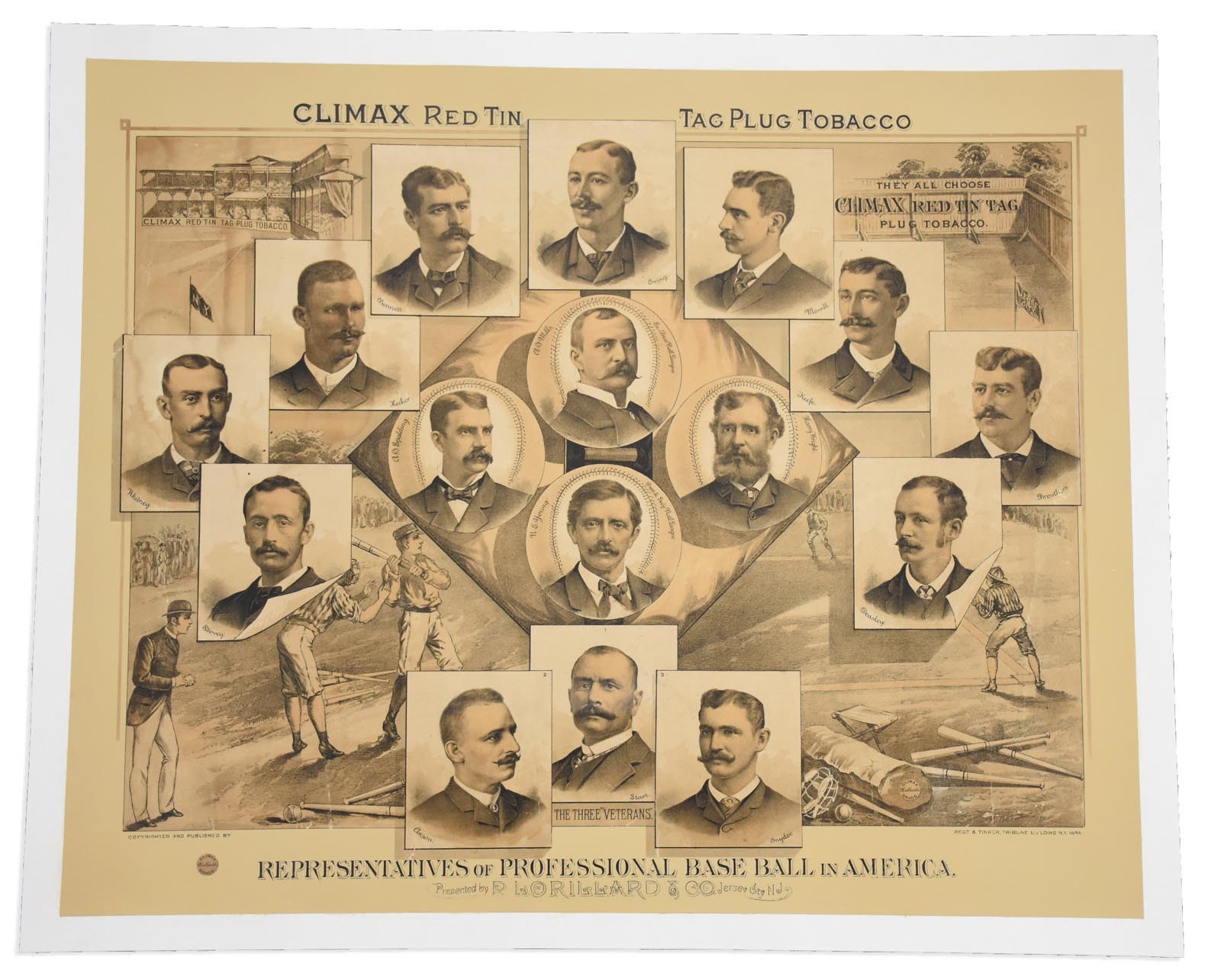

There’s a formula for everything today, but the essential formula is simple: The more runs a player scores, the more he helps his team’s chances of winning. Three players share the distinction of averaging more than one run scored per game during careers longer than 1,000 games. All played in the 19th century: Hall of Famer Billy Hamilton, George Gore, and Harry Stovey. When Hamilton was elected in 1961, Stovey was strongly considered but didn’t quite make it, and in the half-century since then his stock has gone down. In fact, he is virtually unknown today except by aficionados of 19th century baseball, so let’s revisit the remarkable record of this forgotten five-tool star.

He was born in Philadelphia on Dec. 20, 1856, as Harry Duffield Stow. His mother didn’t want Harry to play baseball, so after turning pro, he took the name Stovey so she wouldn’t see “Stow” in the newspapers. A 5-foot-11 1/2, 175-pound outfielder who logged his most time in left field and also played a lot of first base, he spent his first three major league seasons in the National League with the Worcester team.

Stovey broke in as a 23-year-old in 1880, scoring 76 runs in 83 games and leading the league with 14 triples and six home runs. In his final year with Worcester, he scored 90 runs in 84 games, the first of seven times he averaged more than a run per game. Hamilton and Gore did it eight times each, but nobody has done it since Rickey Henderson in 1985 for the New York Yankees

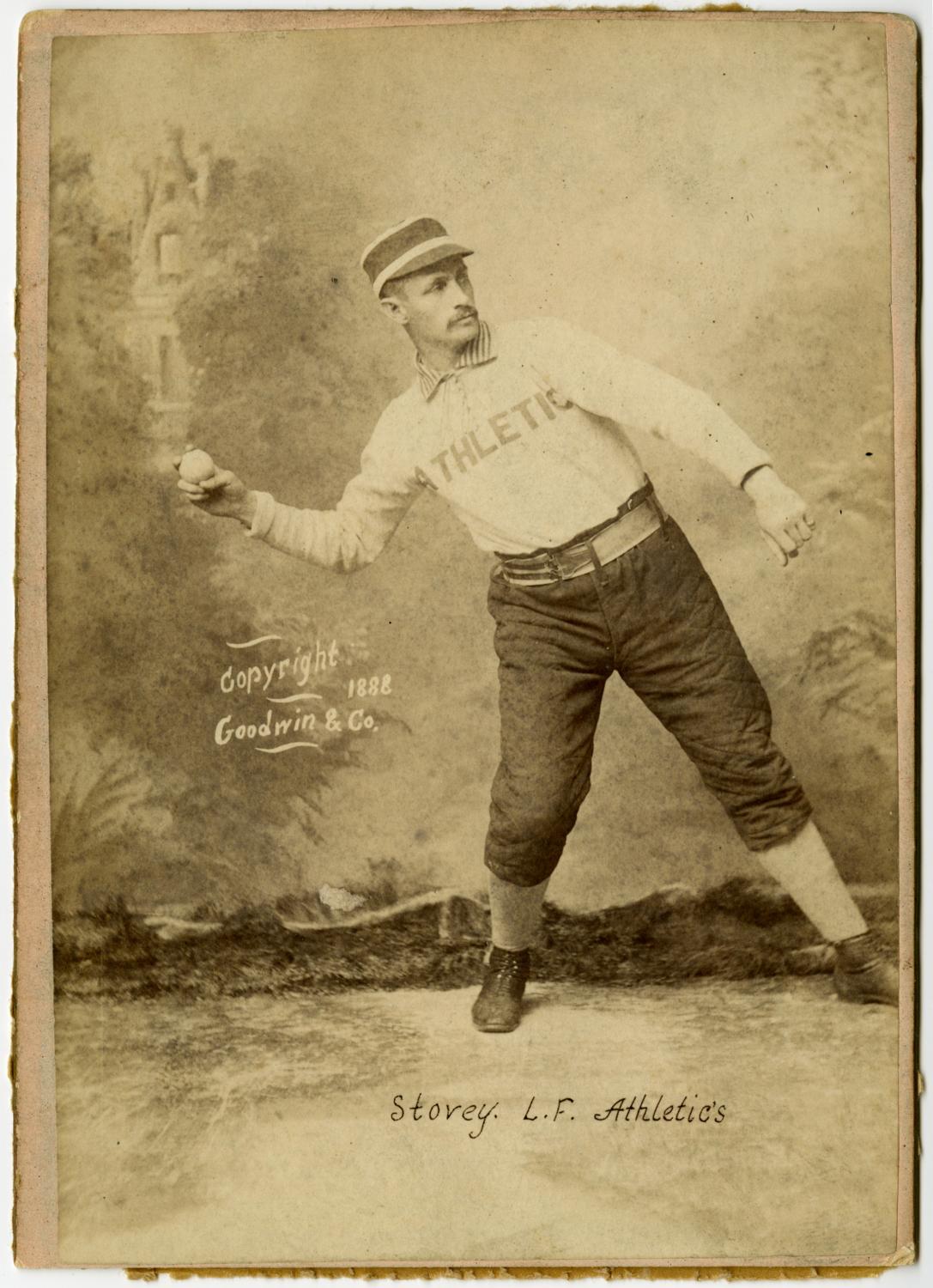

When the Worcester team folded after the 1882 season, Stovey cast his lot with the Philadelphia Athletics of the American Association, which was created in 1882 to compete with the National League. After finishing a distant second in 1882, the Athletics won the pennant in 1883 led by Stovey, who batted .304 and led the league with 31 doubles, a major league-record 14 home runs, a .506 slugging percentage and 110 runs in 94 games.

That began a seven-year stretch during which he established himself as the league’s most formidable one-man force. As noted in the New York Clipper, “Although he is a very hard hitter and an exceedingly clever base-runner, he more particularly excels in the outfield, being an accurate and strong thrower, a sure catch and having the ability to cover a great deal of ground. He is a strictly temperate, honest and ambitious young man and is in every respect a model professional player.”

The raw power numbers tell only part of the story of the seven-year reign of terror staged by this mild-mannered whirlwind known as “Gentleman Harry,” the captain of the Athletics. Playing 117 games a season, less than three-fourths of today’s schedule, he averaged 29 doubles, 13 triples (with a high of 23), and 11 home runs (ranging from 4 to 19), leading the league in homers three times.

Stovey was the first major leaguer to reach 50 career home runs, the first to 100 and held the career record with 122 until passed by Roger Connor in 1895. He finished in the top five in total bases five times, slugging percentage five times, home runs six times and OPS five times.

In another of today’s fashionable statistics, offensive WAR+ (in essence, how far he exceeded an average player), he was third five times and second once. His last season as an Athletic was his best: a .308 average, 38 doubles, 13 triples, and league-leading figures of 19 home runs, 119 RBI, a .525 slugging percentage, and 152 runs.

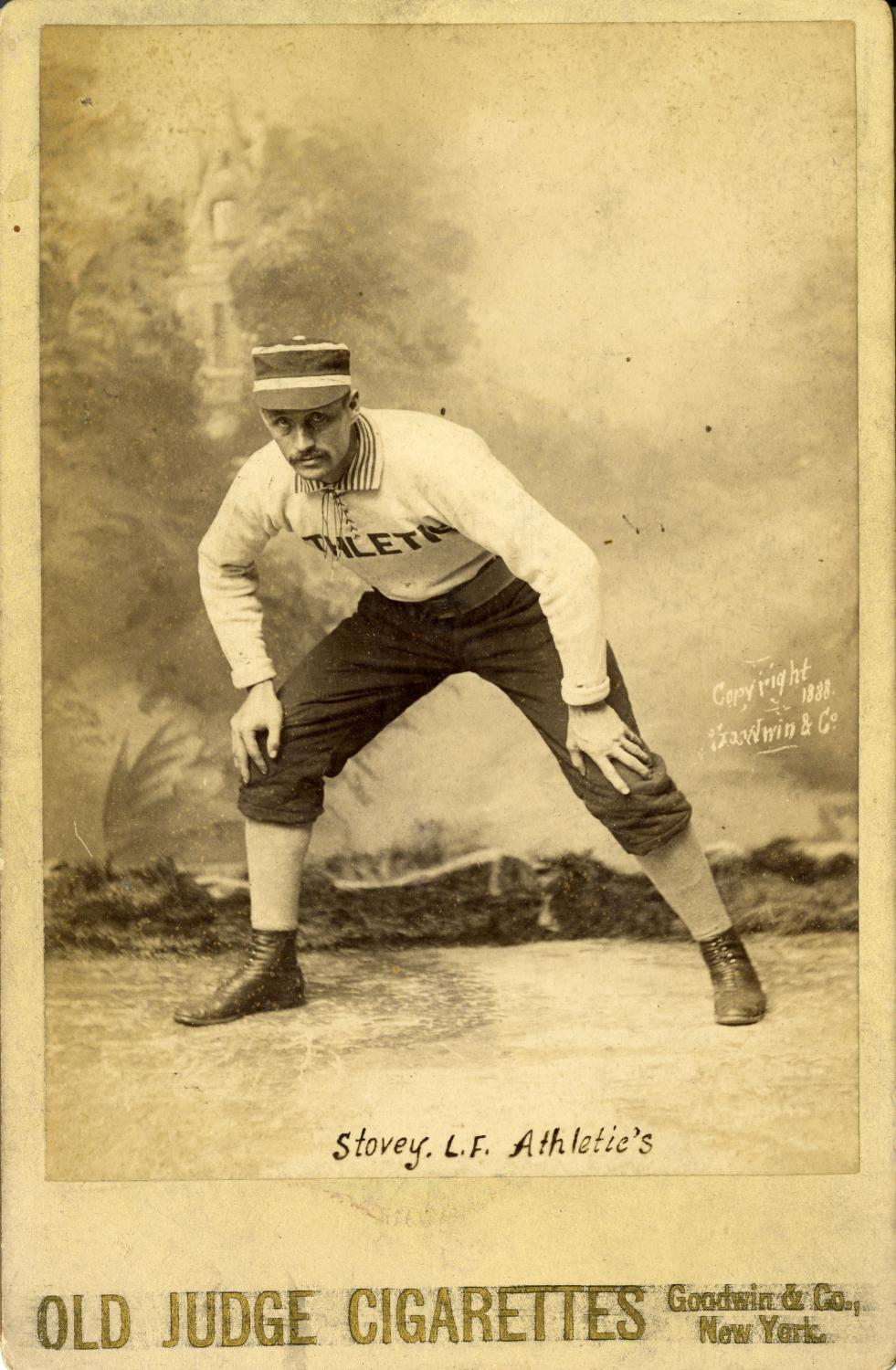

Oh yes, runs. Here are Stovey’s totals for those seven years: 110, 124, 130, 115, 125, 127, and 152. That brings up the real strength of his game: speed. Stolen bases were not recorded until 1886, the seventh season of his career, when he was 29 years old. For the rest of his career, the rules awarded a stolen base when a runner took an extra base, such as going from first to third on a single.

For decades after his retirement, Stovey was championed as the record-holder with 156 steals in a season, but more recent historians have gone back to recalculate steals according to the rules adopted in the mid-1890s and still in effect today. So Stovey’s “official” stolen base figures for the six seasons leading up to his 35th birthday were 68, 74, 87, 63, 97, and 57. The 156 figure gives you an idea of how often he took that extra base. Using the old criteria, there was a period when he held the career record for both home runs and steals. Think about that.

Until recently, Stovey was credited with two major innovations: the feet-first slide , which terrorized infielders much the same as Ty Cobb’s later spikes-first slide, and the invention of the sliding pad, necessitated by the wear and tear on his hips from sliding on his side.

Popular Posts

Best Youth Baseball Bats

Best BBCOR Bats

Best USA bats

Best Softball Bats

Best Wood Bats

Historian Peter Morris, in “A Game of Inches,” discusses the rarity of sliding in baseball’s early decades and the ensuing debate over the relative merits of head-first and feet-first slides. He gives Stovey partial credit for perfecting what we call the “pop-up slide” today, in which the runner gets back on his feet quickly to take advantage of an errant or bobbled throw. According to Morris, however, sliding pads pre-dated Stovey. Still, there is no doubt that Stovey’s base running was advanced and aggressive for his time. He didn’t score all those runs by accident. He was all over the place, and that speed also contributed to his reputation as one of the great fly-chasers in the era before gloves.

One other thing: Could he throw? In 1888, he participated in a distance-throwing contest and finished second to Ned Williamson with a throw of 123 yards, 2 inches, or 369-plus feet. Yes, he could throw. He could do it all.

So why isn’t Harry Stovey in the Hall of Fame? The American Association, where Stovey played in his prime from 1883 to 1889, has always been acknowledged as a true major league, but because its overall quality of play is considered inferior to that of the rival National League, its stars have been downgraded by the Hall’s various Veterans Committees. Although the argument is often made that being the best in your league at your position is a qualification for a plaque in Cooperstown, that logic has not been applied to the American Association. So its greatest stars, including Stovey, Pete Browning (.341 career average), and Tony Mullane (284 career wins), have gotten only occasional support for election.

Keep in mind, however, that even though the National League has endured since 1876, in Stovey’s time the NL was only a few years old. It was going through the same growing pains on and off the field that every other aspiring league experienced.

When John Montgomery Ward organized the Players’ League in 1890, he was able to recruit many of the best players, including future Hall of Famers Dan Brouthers, King Kelly, Hoss Radbourn, Connor, Jim O’Rourke, Buck Ewing, Tim Keefe, Hugh Duffy, Charles Comiskey, Jake Beckley and Pud Galvin. And Harry Stovey.

How did Stovey stack up against this company (at age 33)? Playing alongside Kelly and Brouthers on the pennant-bound Boston Reds, he batted .299 with 84 RBI in 118 games, led the league with 97 steals, and was third with 12 home runs and 142 runs scored. Not bad for a guy well past his athletic prime.

When the Players’ League collapsed following its sole season, Stovey returned to the National League with the Boston Beaneaters, and helped them win the 1891 pennant by putting together his last great season. He led the league in total bases (271), triples (20) and slugging average (.498), tied with Mike Tiernan for the home run title with 16, was second with 95 RBI, fifth with 57 steals, and fifth with 118 runs.

Stovey did slow down in his final two seasons before retiring in 1895 to New Bedford, Mass., where he became a policeman. In 1901, he reportedly dived into the water by a wharf to rescue a 7-year-old boy, and in 1915 he was named police chief, a post he held until he retired in 1923.

When Stovey died in 1937 at 80, his obituary described him as “what Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth were in their day.” How long can the Hall of Fame deny him his place in that pantheon? In 2011, SABR’s Nineteenth Century Research Committee voted Stovey its “Overlooked 19th Century Baseball Legend” for 2011. The winner of the 2010 vote, Deacon White, was elected this year by the Veterans Committee. Stovey’s day will come.