Satchel Paige, “Smokey” Joe Williams, “Cannonball” Dick Redding, and “Bullet Joe” Rogan are often remembered as the top pitchers in the Negro Leagues. But time and time again, Leon Day was their equal and even bested some of these better-known hurlers.

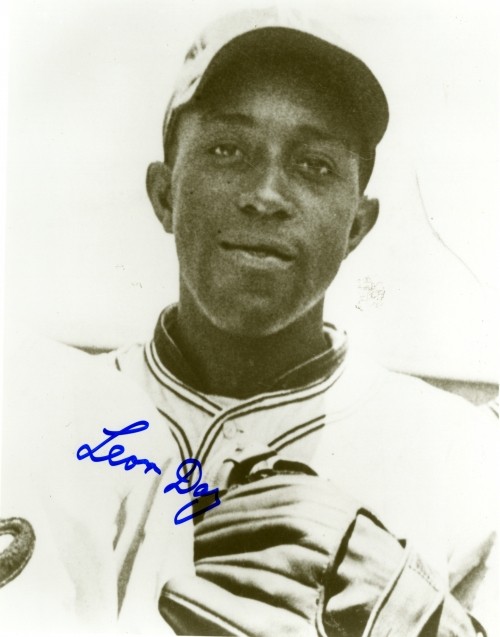

Standing just 5-feet-10 and weighing 170 pounds, Day found a way to dominate hitters with a no-windup delivery that resulted in an outstanding fastball, effective curveball, and quality changeup. Buck O’Neil once said Day could have been a “front-line starter” in the big leagues because he threw “everything quick.”

Unfortunately, Day never reached the majors.

Born in 1916 in Alexandria, Virginia, Day moved to Baltimore with his family when he was an infant. Early on, baseball became his passion, and he often watched games at the old Maryland Baseball Park in the Baltimore neighborhood of Westport. After dropping out of high school at 17, Day began playing for a local semipro team, the Silver Moons. Signed by the Baltimore Black Sox in 1934, he moved to the Brooklyn Eagles of the Negro National League the following season. He was an all-star by 19. “When they told me they were going to pay me to play baseball, I said they must be crazy,” Day recalled decades later. “I said I’d play for nothing.”

According to records at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, Day appeared in a record seven Negro League All-Star Games. That number would have been even higher if he hadn’t missed two seasons because of military service in World War II. In the 1942 All-Star Game, pitching against the legendary Paige, Day faced seven batters and fanned five of them, duplicating Carl Hubbell’s feat in the 1934 Major League All-Star Game. Day didn’t allow a base runner in his remarkable outing, and only the end of the game prevented him from extending his strikeout total.

Many of Day’s memorable games came against Paige. In the fall of 1942, the Homestead Grays lost the first three games to the Kansas City Monarchs. Thanks to a last-minute roster move, Day was named to the team and he pitched a five-hitter, outdueling Paige.

Available records indicate that Day won three of four marquee matchups against Paige. Also in 1942, as staff ace for the Newark Eagles, Day struck out 18 Baltimore Elite Giants to set a Negro National League record. The Pittsburgh Courier rated Day higher than Paige several times, calling him the best pitcher in 1942 and 1943. “Satchel was more flamboyant—he stood out in a crowd,” Day said. “Me, I just did my job. I didn’t open my mouth.” Negro Leagues historian Todd Bolton said Day “was never a self-promoter. . . . He was a humble man and let his record speak for itself.”

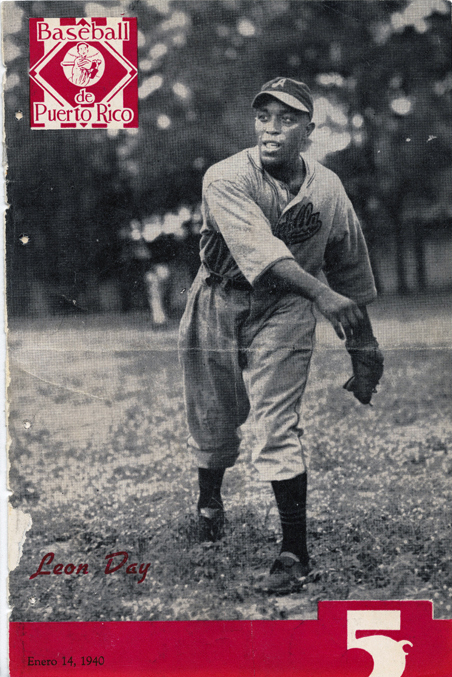

During the offseason, Day gained a following in Mexico, the Caribbean, and South America. In the winter of 1939–40, he struck out 19 in one game to set a Puerto Rican League record. In another contest, pitching for the Aguadilla Sharks, he struck out 15 more. In addition, Day pitched in Venezuela, going 12–1 one season and leading Vargas to the championship there.

In Mexico, he put up a perfect 6–0 record for Veracruz and later returned to play for the Mexico City Reds. And he had several impressive winter ball seasons in Cuba, going 8–4, mostly for the Almendares club.

“He threw that ball more or less from his hip,” Gene Benson, an infielder with the Philadelphia Stars, once told the Society of American Baseball Research. “He didn’t rear back and come right over his shoulder. He came right from his thigh, but he would whistle the ball and make it move. He could bring it.”

Former teammate Monte Irvin claimed Day threw as hard and was as competitive as Bob Gibson, adding that Day “was the most complete ballplayer I’ve ever seen. . . . If we had one game to win, we wanted Leon to pitch.”

Day’s reputation only grew on his pitching off days as he regularly starred in the field. A superb contact hitter and base runner, Day was versatile enough to play second base or the outfield when he wasn’t pitching. “There wasn’t any position he couldn’t really play,” added Irvin, who regularly formed a formidable double-play combination with Day. “He was something to behold, on the mound or in the field.”

A 1941 press release described Day “as the most versatile and outstanding player on the team” and “the most desirable player on any club.” Larry Doby, who played with Day on the Newark Eagles, said that he “didn’t see anyone better than him.”

Unfortunately, Day was taken away from the game in his prime. During World War II, he served in a segregated amphibious unit (helping land supplies after D-Day) and pitched on integrated army teams. In fact, a squad with him and Willard Brown, another future Hall of Famer, upset the 71st Infantry Division Red Circlers in the 1945 European Theater Operations World Series.

After the war, in his first game back with the Eagles, he tossed a no-hitter against the Philadelphia Stars. Despite arm troubles, he went 13–4 and batted .469 that season.

During auditions for big league teams after baseball’s color barrier finally came down, Day was still bothered by a bad arm. When he went unsigned, Day headed south, playing in Mexico and Cuba. After retiring from the game, he worked for a time as a bartender in Newark before resettling in Baltimore, with his family. There, he was a security guard, never forgetting his heyday in the Negro Leagues when he ranked among the best ever. “I was glad to play in the Negro Leagues,” he once said. “I wouldn’t trade it for anything in the world.”

In his final days, Day longed to be selected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. He nearly made it in 1993, only to fall a vote short. Many contend that if Veterans Committee member Roy Campanella hadn’t been ill and forced to miss that meeting, Day would have made it.

Finally, the good news came on March 8, 1995, with Day in the hospital suffering from diabetes and heart trouble. That made him the 12th Negro League representative in the shrine, the first since Ray Dandridge was inducted in 1987 and the first to die between selection and induction.

The soft-spoken pitcher, who could also play so many other positions, died five days later at the age of 78. His wife, Geraldine, gave his induction speech that summer in Cooperstown. At the ceremonies, she told this story. “When I got to the hospital the morning of the vote, Leon was all excited. He told me, ‘Baby, I just heard from the Hall of Fame. I made it! I made it.’ I told him, ‘Leon, honey, it’s 8 o’clock in the morning. They haven’t even voted yet. It must have been a dream.’ . . . Then when the call did come later in the day, it still seemed like a dream.”

Except it wasn’t. Leon Day had indeed made the Hall of Fame, and he lived just long enough to see it.

“I guess he wanted to be with Mule Suttles, Willie Wells, Ray Dandridge, Biz Mackey, and all those other great [Newark] Eagles he played with,” Irvin told historian Brad Snyder. “He didn’t have any time to enjoy the honor that had been given to him, but all of us who played with him will read the list of all-time great pitchers, and Leon Day’s name will have to be at the top.”