During the year that Theodore Roosevelt cruised to reelection as president of the United States, Peter Pan premiered on the London stage, and St. Louis hosted the Olympic Games (which included baseball exhibitions), pitching dominated the 1904 Major League Baseball season. Cy Young threw the first perfect game in MLB history. More than 50 hurlers had earned run averages below 3 at season’s end. Only one American League team (the hapless Washington Senators), in fact, failed to keep its collective ERA in the 2s. The New York Highlanders’ (soon to become the Yankees) Jack Chesbro led the rubber-armed trend of starting pitchers going the distance. He had 48 complete games for the season.

The inability of hitters to get on base and the difficulty that 1904 baseball clubs had scoring runs was indicative of the broader “Deadball Era” in which they participated. As baseball historians have delineated, a combination of factors—the non-corked baseball and large fields especially—created a defensive game. Teams manufactured runs through sacrifices, stolen bases, and hit-and-runs.

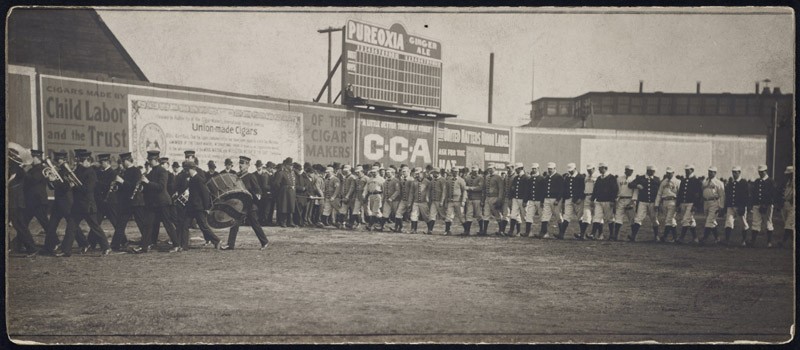

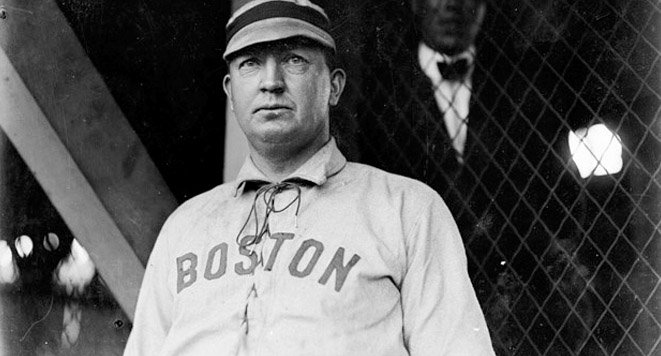

Still, 1904 was an especially pitching-strong campaign. Cy Young, 37 years old, continued to baffle hitters, even if he did not quite possess his most dominant stuff any longer. Young won 26 games in 1904. He led the American League with 10 shutouts and helped the Boston Americans (soon to become the Red Sox) to the pennant. A master of control, Young struck out nearly seven batters for every one that he walked. On May 5, 1904, at Boston’s Huntington Avenue Grounds (the club wouldn’t move to Fenway Park until 1912), Young pitched a perfect game versus the Philadelphia Athletics. It was baseball’s first perfecto, a “sermon” on masterful pitching and clean living, according to one newspaper. “Pitching against the strong Philadelphia team, he made an absolute perfect record. Exactly 27 men, the minimum number possible, faced him; he did not allow one hit, did not give a base on ball, struck no batsman and made no fielding error.”[i] TheWashington Times called witnessing the performance, “the treat of a lifetime.” The Boston home crowd, one of the largest of the season, celebrated their ace. “Ten thousand voices, keyed to the highest pitch, went off as if by electric shock as the last man went out . . . clinching the greatest game ever pitched by a mortal man.”[ii]

Young helped Boston to a late-season surge that pushed them past the Highlanders for the AL pennant. The Highlanders had a bounty of effective pitchers too, including the aforementioned Jack Chesbro. “Happy Jack,” a stocky right-hander, made 51 starts, logged 454 innings, and won 41 games. These totals presently stand at first, second, and first, respectively, in the American League record book.

The leading batters of the 1904 season, at least in terms of batting average, were both midways through Hall of Fame careers. Nap Lajoie led the American League with a .376 average while Honus Wagner hit .349 for the NL batting title. Both men had more than 40 doubles. Neither hit many home runs; Harry Davis of the Athletics led baseball with 10 round-trippers for the season.

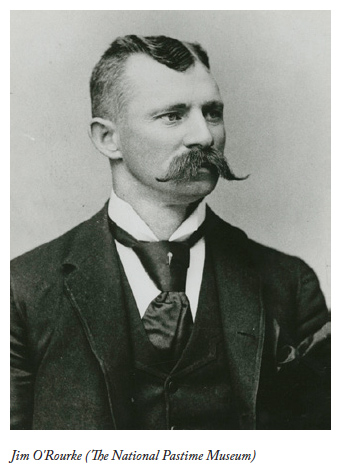

As the season wound down, Boston pulled ahead in the AL while the New York Giants ran away with the National League pennant. With a 13-game lead in the standings heading into the final day of the season, the Giants celebrated by starting a 53-year-old catcher. Yes, 53. Jim O’Rourke, a member of the 1889 championship Giants, caught all nine innings of the Giants’ final-day victory. He even got a hit in one of his four at-bats to cap off the celebratory move.

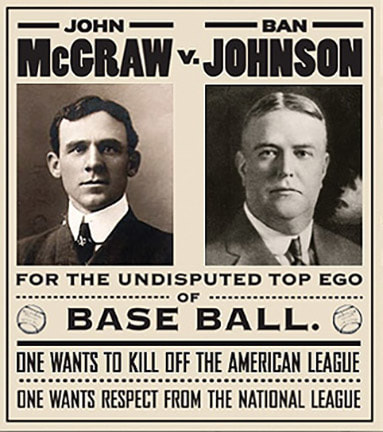

While the individual exploits of the 1904 season—from Young (Cy) to old (O’Rourke)—make for fun baseball reading, the most historically significant aspect of the season came at its end. Unlike the 1903 season, or the 1905 through 1993 baseball seasons, the 1904 campaign did not conclude with a World Series contest. The tenuous agreement that led to the initial fall classic in 1903 could not be replicated. John McGraw, the ornery manager of the NL Champion Giants, would not allow his team to take the field versus the Boston Americans.

Also Check: Is Managing Major League Baseball Clubs difficult now?

The seeds of this 1904 postseason dispute had been planted and cultivated over the prior two decades. As Ban Johnson led the insurgent American League to prominence at the tail end of the nineteenth century, McGraw played a prominent role in the struggle between baseball’s two most important leagues. McGraw had jumped to the American League in 1901 to play for and manage the AL’s Baltimore club. While he only lasted for a season and a half in the AL, he managed to embroil himself in a feud with Ban Johnson during his AL tenure. The two argued incessantly, especially over the still-emerging rules and codes of baseball. Frustrated, McGraw went back to the NL in 1902 when the New York Giants offered him a player/manager slot.

McGraw was not about to let bygones be bygones. He didn’t care if the press and fans wanted an interleague championship. “Either New York [Highlanders] or Boston would be delighted to play the New York Nationals [Giants] for the world’s championship,” a Louisville paper reported. “And the large majority of baseball; patrons everywhere would like to see such a series, but the matter has been disposed of finally by the flat refusal of Brush and McGraw to permit their team to play.”[iii] As pressured mounted in October for the Giants to relent and take part in the series, McGraw held firm. He issued a statement that promised he would never submit to a series with an American League club. “I know the American league and its methods. . . . Never while I am manager of the New York club and while this club holds the pennant, will I consent to enter into the haphazard box office game with Ban Johnson and Co.”[iv]

McGraw could not be mollified; the 1904 World Series went unplayed. McGraw would, of course, change his mind and the Giants would take part in the 1905 World Series. But the year 1904 in baseball, along with the strike-shortened 1994 baseball season, stands out for its lack of a concluding series. It was a strange and noteworthy season.

[i] Cambridge Jeffersonian, May 19, 1904.

[ii] Washington Times, May 6, 1904.

[iii] Courier-Journal [Louisville], October 10, 1904.

[iv] Saint Paul Globe, October 13, 1904.