Last year I read a story by ESPN.com’s Jerry Crasnick, with this headline:

Why managing is harder than ever

Within the actual story, Crasnick doesn’t make that argument, precisely. Anyway, his interviewees do most of the arguing. And they’re arguments I’ve seen before, here and there over the years.

In Crasnick’s story, he quotes Tony La Russa: “In the old days it was all about the power of the position. You were the manager and you said, ‘We’re going to do this,’ and the players said, ‘Yes sir.’ Now it’s your responsibility to earn their respect and trust. Then you personalize it by showing that you care about them. It’s really about back-to-basic values.”

We all like to believe that we live in a special time and must surmount obstacles that our lesser forebears didn’t. To be sure, La Russa and his contemporaries have dealt with obstacles hardly imagined 50 or 100 years ago. Still, I think it’s instructive to look at managing and what we might call (for lack of a better word) durability.

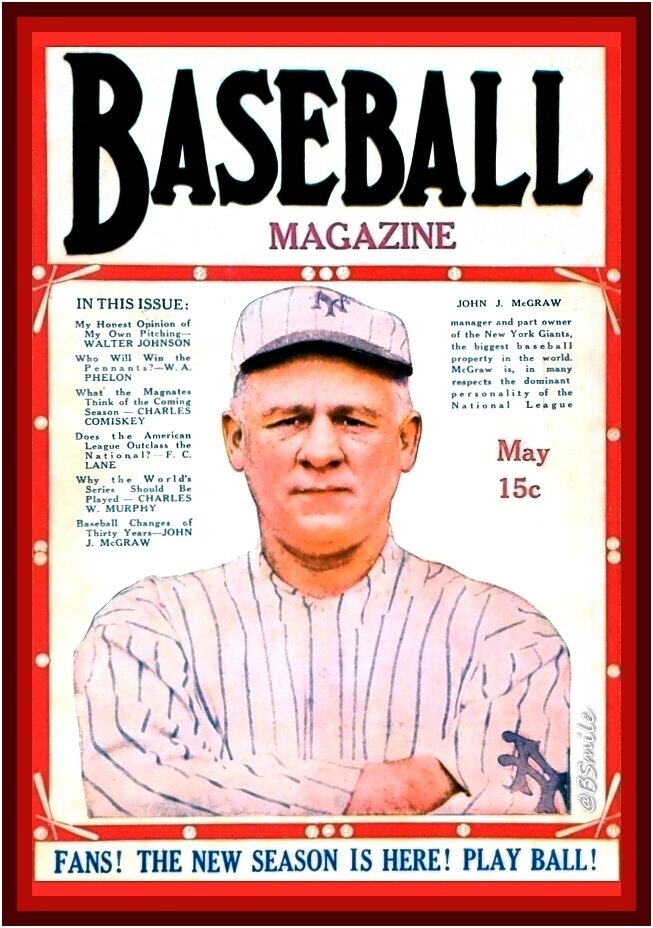

Hall of Famer John McGraw managed forever: 33 seasons, give or take.

McGraw was 59 years old when he retired in 1932, due to various health problems.

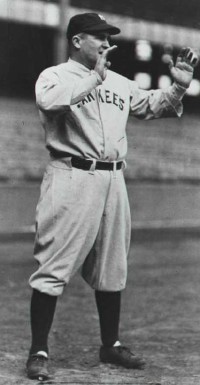

Hall of Famer Joe McCarthy managed for 24 seasons, give or take.

He was 63 years old when he quit in 1950. McCarthy wasn’t particularly well at the time . . . but on the other hand he lived for nearly 28 more years.

Hall of Famer Billy Southworth was only 58 when he quit for good in 1951, but he would live for another 17 years.

Like McGraw, McCarthy, and Southworth, Bill McKechnie would eventually gain election to the Hall of Fame as a manager. In 1946, shortly after turning 60, McKechnie “resigned under pressure” as Reds manager. He would not manage again, despite living in (mostly) good health for another 15 years.

Finally, there’s Al Lopez, another Hall of Fame manager. Lopez got his start just as McCarthy and Southworth’s careers were ending. He would manage the Indians to an American League pennant in 1954, and the White Sox to another in 1959. After a third straight second-place finish in 1965, Lopez retired, reportedly suffering from both insomnia and chronic stomach ailments. He did return to manage the Sox in 1968 but quit in ’69 after 17 games. He was 60, never managed again . . . and would ultimately celebrate his 97th birthday.

Now let’s look at a comparable group of managers, achievement-wise.

In 2015 three managers were enshrined in Cooperstown: Tony La Russa, Bobby Cox, and Joe Torre.

La Russa retired (from managing, in good health) at 67.

Bobby Cox retired at 69.

Torre retired at 70.

Not so coincidentally, La Russa, Cox, and Torre rank third, fourth, and fifth on the all-time list for managerial wins in the Major Leagues.

A bit farther down the list are Lou Piniella and Jim Leyland. Piniella retired just short of his 67th birthday, Leyland just short of his 69th.

This summer, Giants Manager Bruce Bochy should pass Leyland on the career list, with Piniella next in 2017. Bochy turns 61 this spring, with no signs of slowing down.

Meanwhile, the Nationals just hired Dusty Baker, at the ripe young age of . . . 66.

Now, before going any farther along this line of argument, I should and must acknowledge two things. Well, maybe more than two things. But I will acknowledge only two things now.

One, of course the American population is living longer today than it did in Billy Southworth’s time. And two, of course none of the above serves as prima facie evidence of . . . well, of anything really.

Still, it might mean something, that managing used to be a game for middle-aged men, and now it’s become a game for old men? Hell, I haven’t even mentioned Jack McKeon yet. He managed the Marlins to a World’s Championship when he was 72, and he later managed them for 90 games when he was . . . 80.

Okay, third thing to acknowledge: Connie Mack.

Connie Mack managed until he was 87 years old. Yes, he did own the team. And yes, toward the end he got an awful lot of help from his coaches. But Connie Mack remains essentially the only twentieth-century manager we might reasonably describe as old. At least by our modern standards.

Okay, so there’s my purely age-based case for managing being more difficult in the old days. So what is the case for managing being more difficult today?

Well, Crasnick’s argument last July rested largely upon “the all-around carnage that MLB managers have been subjected to since Opening Day,” which included three firings, Ryne Sandberg’s resignation, and various managers supposedly on the hot seat.

Was this really so out of the ordinary, though? In 1951, five managers were fired during the season and another resigned . . . and remember, in ’51 there were only 16 Major League franchises. When making historical comparisons—not that Crasnick was making one—we always need to remember that there were only 16 MLB franchises until 1961, only 20 until 1969, etc.

And while Crasnick was writing in early July and four managerial changes seemed like a lot, those were the only in-season managerial changes (excluding Red Sox Manager John Farrell’s leave of absence while undergoing treatment for Stage 1 lymphoma; Farrell’s back in the dugout in 2016).

Certainly, some things have changed over the years. The stakes are higher, at least financially. The season is longer, potentially running from early February until early November. And the media demands are greater than ever, with some managers expected to conduct a full-blown press conference after every game.

But then, haven’t the stakes always been high? Didn’t the owners and the fans of the Giants and the Cardinals want to win just as much in 1936 as in 2016? In the old days, the managers were islands. Today, they’re insulated by hitting coaches and pitching coaches and bench coaches and media-relations people. Oh, and if they’re fired? They probably won’t have to worry about paying their mortgage.

In the spring of 2015, the Brewers exercised their 2016 option on Manager Ron Roenicke . . . and less than two months later, they fired Roenicke, who was nevertheless guaranteed his considerable salary for the remainder of 2015 and all of 2016. This isn’t to suggest that getting fired is either fun or profitable. But guaranteed contracts for millions of dollars do tend to promote one’s peace of mind. Ease one’s day-to-day stress, even.

Again, there was little to relieve the stress of the old-time managers. If the players weren’t playing well, they didn’t have many options. Last year the Dodgers used 16 starting pitchers. In 1935, the Dodgers used 16 pitchers, period (and only 11 of them pitched more than twice). If the hitters didn’t hit, it was the manager’s fault; there weren’t any hitting coaches hanging around as scapegoats. There were pitching coaches, but nobody really paid much attention to them.

Many managers were largely responsible for all sorts of other things, like the organization of spring training, even player acquisitions, and, more than anything else, the crushing responsibility for his team’s fortunes.

One of the stories that’s largely been forgotten, lo these decades later, is just how many managers simply cracked under the strain of managing.

McCarthy left his jobs with the Yankees and the Red Sox because of ill health. But again, McCarthy lived for a long time; one can’t help wondering how much illness was due to the stress of the job (not to mention the rumors of heavy drinking).

In 1948, Billy Southworth managed the Boston Braves to their first championship since 1914. In 1949, the Braves didn’t play nearly as well. On August 17, Southworth took a leave of absence, reportedly due to illness. But according to Southworth’s biographer, “Most observers believed he was on the verge of a nervous breakdown.”

He did come back to manage the Braves in 1950 but quit for good in June 1951.

Oh, Mickey Cochrane. A great, Hall of Fame catcher with first the Athletics and then the Tigers, taking over as Detroit’s player-manager in 1934.

Cochrane’s Tigers lost the World Series in ’34, and won in ’35. After which, having also been handed the reins as general manager, he suffered a nervous breakdown in 1936.

In 1937, Cochrane suffered a near-fatal beaning and never played again. In 1938, he was fired as manager and never appeared in uniform again.

I suppose it’s not surprising that we’ve forgotten just how many old-time managers, including a few in the Hall of Fame, were driven nearly mad by the pressures of the job. But what’s maybe a little surprising is how men like Tony La Russa, who should know better—should know a lot better—seem to have forgotten just how difficult managing used to be.

La Russa’s history lesson notwithstanding, there has NEVER, EVER been a time when the players responded to orders with a simple Yes, sir. Baseball history is littered with famous player rebellions, from the 1926 Pirates to the 1940 Cleveland Crybabies to Southworth’s ’49 Braves to Billy Martin’s Yankees and too many teams in between to count. Strains like those, along with many others, often were simply too much for managers to withstand for long.

We all like to think we’re special. Hey, we are special!

But we’re no more special than our fathers, and our grandmothers.