Part 3

Now that we’ve established how gambling was entrenched in baseball culture as far back as the 1860s and how baseball officials had numerous opportunities to get rid of its worst offender, Hal Chase, let’s take a look at the most farcical game-fixing incident of the Deadball Era.

If there was ever any doubt as to how openly gamblers were allowed to operate at major league ballparks in the early 20th century, the notorious Gamblers Riot at Boston’s Fenway Park on June 16, 1917, should have expelled it forever. That business went on as usual after such a public spectacle illustrates just how little attention American League president Ban Johnson and other baseball officials paid to the gambling menace that would soon threaten to destroy the game with the Black Sox Scandal.

Looking back nearly a century later, it’s hard to believe the Fenway Park Gamblers Riot actually happened. The closest comparison for sports fans in the 21st century might be the infamous “Malice at the Palace,” a 2004 brawl during an NBA game in Auburn Hills, Mich., that spilled into the stands. But while the NBA took measures afterward to increase security and punish the participants, baseball officials in 1917 only increased their rhetoric after Boston gamblers invaded the field (twice!) and fought with opposing Chicago White Sox players.

The Sporting News called it “one of the most disgraceful scenes ever witnessed in a major league ball park.” And it was no coincidence that the Gamblers Riot happened in Boston. World Series involving the Red Sox, in 1903 and 1912, had been plagued by rumors of game-fixing, and heavy betting was common on the team’s games.

By the time Harry Frazee bought the Red Sox in 1916, the city was regarded as the biggest center of baseball gambling in the country. An American League investigator later reported that Frazee “entertains more gamblers in his right field pavilion every day than the rest of the majors combined.”

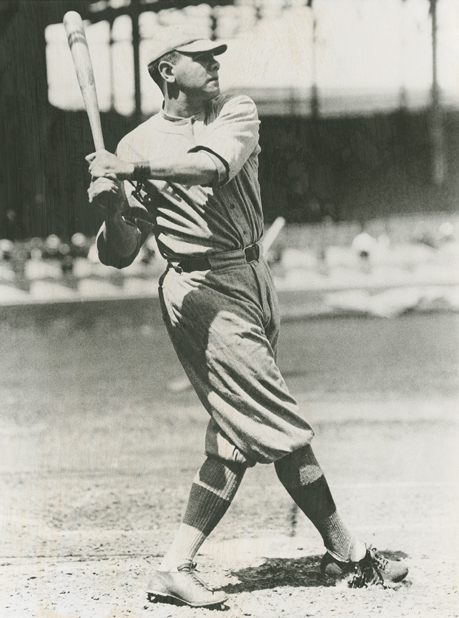

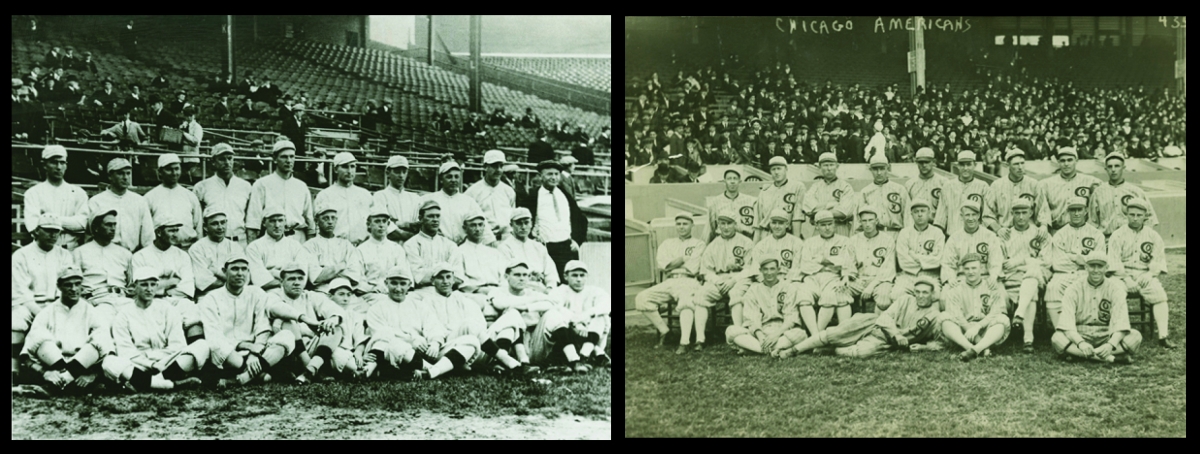

Entering the June 16 game against Chicago, Boston had lost eight of its last 11 games, but hometown bettors were confident that Babe Ruth, their 22-year-old star pitcher from Baltimore, could stop the rare losing streak. The Red Sox were two-time defending World Series champions and just 2 1/2 games behind the first-place White Sox, who were sending ace Eddie Cicotte to the mound.

A violent thunderstorm had pounded the Eastern seaboard the previous day and most of the 9,405 fans who filed into Fenway Park for the 3 p.m. start took precautionary cover under the roof that hung over the infield box seats. The usual contingent of “sporting men” took their customary spots in the right-field bleachers. Frazee claimed he had recently installed a special police force in that section to break up the gambling, but reportedly only five or six police officers were on duty that day.

The atmosphere was tense from the start. Umpire Tommy Connolly ejected hot-headed Red Sox pitcher Carl Mays in the second inning for arguing from the bench. By then Chicago had taken a 1-0 lead on an RBI double by Shoeless Joe Jackson. The crowd began to get restless as a steady drizzle fell.

In the fourth inning, after the White Sox scored a second run-off Ruth, the rain grew heavier, and a few fans from the outfield bleachers ran across the field to the covered pavilion, stopping play for several minutes. Cries of “call the game!” were heard as Cicotte shut down the Red Sox hitters in order in the bottom half of the inning. The Boston Globe reported that “it seemed as if every man in the bleachers was shouting.”

Ruth recorded two quick outs in the fifth. Then, as leadoff hitter John “Shano” Collins stepped to the plate for the White Sox, all hell broke loose.

A crowd of about 300 fans, led by “some tall man in a long raincoat,” suddenly began leaping over the right-field fence and marching onto the playing field. Umpire Barry McCormick immediately called time and “stood gazing in amazement.” But as the Chicago Tribune reported, “They didn’t rush at the players or umpires. Instead of fighting, the mob simply surged out upon the field … and stood around.”

They were stalling for time. If the rain continued, the field would be deemed unplayable, and the game would have to be called. Any hometown bettors who had wagered on the Red Sox would not lose their money.

Connolly, an original American League umpire since 1901, looked around for help from the police. The few officers present could not be found. Connolly and Red Sox manager Jack Barry took charge and persuaded the mob to leave the field so Boston did not have to forfeit the game. But the fans didn’t return to their seats in right field. Instead, they climbed into the infield grandstand. Just when play was about to resume, “new leaders and recruits came from the gamblers’ stand . . . then the first crowd piled out of the boxes again. This time, the mob was riotous,” the Tribune reported.

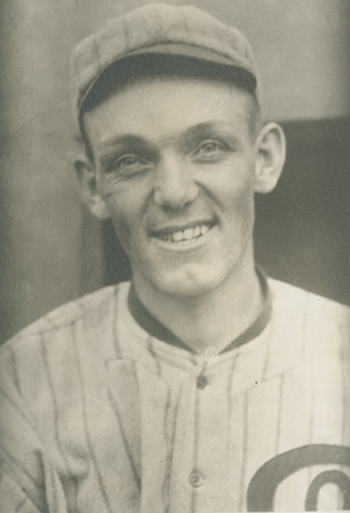

McCormick ordered the Red Sox off the field, and both teams attempted to exit under the stands through the Boston dugout. A melee ensued with the mob converging on the players. White Sox catcher Ray Schalk verbally berated Police Sgt. Louis Lutz for several minutes “in language not suitable for parlor.” The White Sox were forced to fight their way off the field. Infielder Buck Weaver was never one to back down from a brawl. He grabbed a baseball bat and started swinging in all directions. Utility man Fred McMullin used a more traditional weapon — his fists — to get away. Both teams managed to escape safely to the clubhouse.

Boston police eventually sent officers on horseback from a nearby station to restore order. Said the Tribune: “It was the boldest piece of business ever perpetrated by a baseball crowd.” The Sporting News later added, “All the rowdyism that could be crowded into a season cannot do the game half as much damage as the one incident that occurred in Boston.”

Despite the gamblers’ efforts — or maybe because of them — umpires McCormick and Connolly ordered the game to resume. But they encountered surprising resistance from Red Sox owner Frazee, who inexplicably refused to permit his groundskeepers to remove the tarpaulin that covered the field. McCormick pulled out his watch and gave Frazee an ultimatum: Remove the tarp or forfeit the game. Frazee finally relented.

After an approximate 45-minute delay, Collins resumed his long-awaited at-bat with two outs in the fifth inning. He flied out to center field.

The White Sox extended their lead to 3-0 in the sixth on a two-out RBI single by Happy Felsch, and Cicotte continued his shutout through the first seven innings. The Red Sox cut the lead to 3-2 in the eighth, but the White Sox put the game out of reach in the ninth, scoring four more runs to win 7-2 with the big blow being Buck Weaver’s rare home run over Fenway’s 31-foot-high wooden left-field wall (not yet painted green or called a Monster).

The fans did not appreciate his efforts; Weaver reportedly dodged a pop bottle thrown at him after the game. But the mounted policemen kept violence to a minimum as the White Sox left the ballpark.

Their troubles, however, were not over. After an off day Sunday, the teams returned to Fenway Park on Monday, June 18, for a Bunker Hill Day doubleheader. Between games, Weaver and McMullin were served with arrest warrants for allegedly assaulting Augustine J. McNally, a 37-year-old paper mill worker from Norwood, Mass.

With tongue planted firmly in cheek, the Tribune reported that “during the fussing, [McNally] is supposed to have bumped McMullin’s fist with his eye. Also, he is supposed to have had his fingers on the railing just when Weaver let his bat fall.”

The charges were deferred until the White Sox’s next trip to Boston and pushed back again in July. When Chicago returned in late September, accuser McNally did not show up in court and the judge talked baseball with the two White Sox players before dismissing the charges. By then the Sox were cruising to the pennant. They defeated the New York Giants in a six-game World Series.

President Johnson, meanwhile, was livid after the Gamblers Riot. He announced to the press that gambling “had never been tolerated by our league” and it would be stamped out in Boston “regardless of cost.” He pressed Frazee to take action against the gamblers and made a special trip to Boston to investigate the matter.

Frazee rightfully suspected that Johnson was more interested in going after him instead. He was the first owner not handpicked by AL founder Johnson, who resented his mere presence in the league. Indeed, Johnson soon began publicly suggesting — or threatening, depending on your perspective — that Frazee would have to sell the team. (After pawning off most of the Red Sox’s star players to the Yankees, the financially distressed Frazee did sell in 1923, but not because of Johnson.)

Despite Johnson’s rhetoric, gambling remained as pervasive as ever, particularly in Boston. The following year, Lee Magee and Hal Chase of the Cincinnati Reds were accused of throwing games to the Boston Braves. And in 1919, the Black Sox Scandal had its roots at Boston’s Hotel Buckminster, where Chicago first baseman Chick Gandil met with gambler Joseph “Sport” Sullivan” to plan the fixing of the World Series.

As the historians Harold and Dorothy Seymour wrote in Baseball: The Golden Age: “The evidence is abundantly clear that the groundwork for the crooked 1919 World Series, like most striking events in history, was long prepared. The scandal was not an aberration brought about solely by a handful of villainous players. It was a culmination of corruption and attempts at corruption that reached back nearly 20 years. Nevertheless, when the scandal of 1919 became public knowledge, the men who controlled Organized Baseball acted as thought it were a freakish exception, a sort of unholy mutation.”

Two men helped restore public trust in baseball after the Black Sox Scandal threatened to destroy it. One was commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who banned Weaver, McMullin and six of their teammates for life. The other was George Herman Ruth — the Red Sox’s starting pitcher in the Gamblers Riot game on June 16, 1917. He moved to the outfield in 1918 and . . . well, you know the rest.