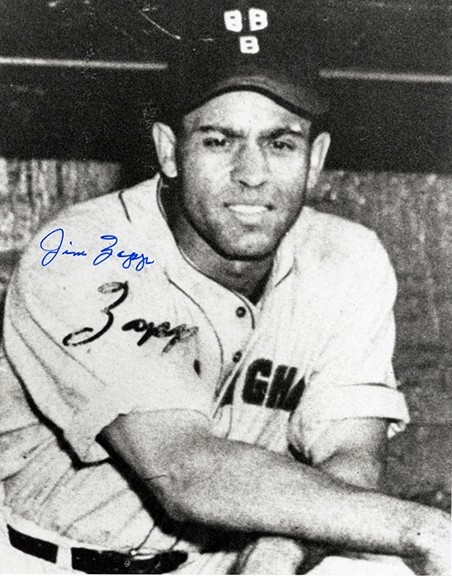

Jim “Zipper” Zapp played a big role in getting the Birmingham Black Barons to the 1948 World Series against the Homestead Grays—the last time there was a World Series in the Negro Leagues. The season had seen a young rookie named Willie Mays spell him in the second game of a doubleheader. Zapp was a big right-handed outfielder, standing 6 feet, 2 or 3 inches and weighing 215 to 230 pounds.

He might have played more but got branded as temperamental. “But I didn’t call it temperamental,” he told Brent Kelley. “If I didn’t think the owners was treating me right, I’d quit, ask for my release, or whatever, as long as they didn’t give me my money. Sometimes they did not.”[1]

James Stephen Zapp was born in Nashville on April 18, 1924.[2] Because of the racial mores of the day, his family history is a little difficult to understand. His father, Burt Zapp, was a baker by trade; his birth mother was Ardina Jordan. Jim Zapp was born to a white man and a black woman. As James Zapp Jr. explained late in 2015, “My granddad was of German-English descent . . . as white as snow. My grandma was black. My dad was born in what you call ‘out of wedlock’ because back in those days white guys could not be with black women.”[3]

Jim went into military service during World War II, early—in 1942, and that’s said to be where he first truly got involved with baseball. He was a Boatswain Mate Second Class (BM2) in the US Navy and was stationed in Hawaii at Pearl Harbor. There, he started playing ball for the Aiea Naval Barracks team—first the all-black team “and then joined the barracks’ integrated team. He also played at Manana Barracks in Hawaii.”[4]

Indeed, Zapp may have integrated the team: “One day we were playing and the manager for the white team was watching us play. I was playing third base at the time. His name was Edgar ‘Special Delivery’ Jones. He was an All-American football player from the University of Pittsburgh. . . . He saw us play and he integrated the white team at that time. He took me and the first baseman . . . Andy Ashford.”[5]

Zapp’s team won back-to-back titles in 1943 and 1944.[6] Before the war was over, he had been transferred back to the States in April 1945 and played baseball for the Navy at Staten Island that summer.[7] He was one of two black players on the team, playing for Manager Larry Napp, who later umpired over 3,600 American League games from 1951 to 1974. Among those he had played with or against were Johnny Mize, Joe DiMaggio, Phil Rizzuto, and Pee Wee Reese.[8]

Later in the year he was also reportedly “signed by ‘Fat Puppy’ Green to join the Baltimore Elite Giants winter season,” playing on weekends as a part-timer. In 1946 he “returned to Nashville to complete a season with the Nashville Cubs.”[9]

In 1947, he says he was traded to the Atlanta Black Crackers and played with them for about half the season. He’d hit 11 homers for Atlanta in the time he was with them, and so he had to some extent proven his abilities.[10] But Jim told Kelley that when the team went to New York to play, where his mother and sister were living, “I quit the team right there because of the owner of the Atlanta Black Crackers; you had to almost fight him to get your money.”[11]

Back in Nashville, he said, “I was uptown one day, standing in front of a nightclub, and a fella from the Memphis Red Sox, T. Brown, was coming through Nashville and he saw me. He said, ‘I heard you quit playing baseball.’ I said, ‘Yeah, I’m giving it up. I can’t stand it no more.’ He said, ‘Would you go back to playing if I recommend you to the Birmingham Black Barons?’ I told him, ‘Yeah, I’d go to the Black Barons.’”[12]

John Klima writes that Zapp had “a tan complexion that allowed him to pass in many social circles. He also learned that being light-skinned sometimes meant exclusion from both groups. This hurt and haunted him throughout his early years, but he found complete acceptance in black baseball.”[13]

He joined Birmingham during spring training at Alabama State University in Montgomery and played left field for Manager Piper Davis. Davis had Ed Steele play in right field, with Norman Robinson in center. Rookie Willie Mays joined the team after school got out and would sometimes sub for Zapp in left during the second game of doubleheaders, but when Robinson broke his leg later in the season, Mays was brought in to play center. He hadn’t yet developed his hitting skill and power, but his fielding was strong enough to keep him in the spot. When Robinson returned, Mays was moved to left field, leaving Zapp the odd man out for a while. Years later, Zapp very graciously said of Mays, “Here we thought we was the ones makin’ him better, but it was the other way around.”[14]

Original artwork by Mark Chiarello.

Willie Mays, Birmingham Black Barons.

Original artwork by Mark Chiarello.

Zapp was brought back in time to play a key role in the 1948 playoffs. “The highlight of my career was in 1948 when I was playing with the Birmingham Black Barons against the Kansas City Monarchs.”[15] The two teams had matched up well and gone into Game 5 of the league championship series. The Monarchs were up by a run, 3–2, but Zapp homered in the bottom of the ninth to tie the game.[16] Another run followed, and the Black Barons held a one-game edge in the playoffs. They won the Negro American League pennant and went on to battle against the Homestead Grays in that year’s World Series.

After the season, he quit again. There was a barnstorming tour put together, the Indianapolis Clowns against a team playing with Roy Campanella and Jackie Robinson. “They picked all the boys from Birmingham to go with Jackie Robinson and Campanella and they put me with the Clowns. I got upset again, so I told them just to give me my release. And they did, they gave me my release. That’s probably one of the biggest mistakes I ever made in my life.”[17]

“Piper always used to say I was the biggest fool he had ever seen,” Zapp said. “He said, ‘You quit a championship team over a few dollars.’”[18]

Zapp played semipro ball in the Nashville area for the next couple of years—in 1949 for the Morocco Stars and in 1950 for the Nashville Stars. Jim Riley reports that he returned to the Baltimore Elite Giants “in the latter part of the 1950 season . . . and remained with them in 1951.”

During that 1951 season, he was said to have been “playing the best ball of his entire career,” but when he was not selected to the midseason East-West All-Star Game, he “immediately became disgruntled and left the team right there on the spot.”[19]

In 1952 he entered what was then called “organized baseball” by signing with the Paris, Illinois, team—the Paris Lakers—in the Class-D Mississippi-Ohio River Valley League. The 1951 Lakers had won the flag with ease, finishing 15 games ahead of the second-place Centralia Zeros. In 1952, Danville won by two games over Paris. SABR’s Minor League Database shows teammate Clint “Butch” McCord with a .392 average and 15 homers, with Zapp playing in 122 games, homering 20 times, and batting .330.[20] Zapp’s 136 RBIs led the league; years later, memory was that he still held the league record.[21] Zapp was named as the league’s all-star left fielder.[22]

Zapp said, however, “Something happened during the season that they didn’t like about my personal life, so they gave me an unconditional release during the winter.”[23] This time, it wasn’t Zapp electing to leave. They released him because he was dating a white woman. They could have sold his contract to a Major League team, but they released him outright, which prevented him from catching on with a Major League team.[24]

He played very little in 1953, 11 games with Danville and three for Lincoln.

After spring training at Corpus Christi, Texas, in 1954, he remained with the Corpus team “for three or four days and Corpus Christi came up with the idea that they weren’t ready for a Black ballplayer yet so they optioned me to Odessa, Texas. . . . I inquired about Odessa from some of the guys in a barbershop and they said, ‘Man, you don’t want to go to Odessa. That’s nothing but sandstorms, tumbleweeds, and rattlesnakes.’ So I took my train fare and instead of going to Odessa I came back to Nashville.”[25] He quit.

Also Check: THE BIZARRE DEATH OF LEN KOENECKE

Zapp played the 1954 and 1955 seasons in Big Spring, Texas—two full and productive years in the Class-C Longhorn League. His 32 homers—in just 90 games—led the team in 1954; Zapp drove in 86 runs and hit for a .290 batting average. In the last month of the season, he had returned to the Negro American League to play both for the Elite Giants and the Black Barons.[26]

In 1955, Zapp hit 29 homers and batted .311 for Big Spring, and then he played his last 39 games in an organized ball for the Class-B Port Arthur Sea Hawks (Big State League).

Zapp decided to leave baseball and took a position in Big Spring in 1956 as a sports director with the United States Air Force’s Civil Service, as the athletic director at Webb Air Force Base and the base at Fort Rucker, Alabama, until he retired in 1982.

“In addition” to simply enjoying his retirement, Jim Zapp said, “I coached youth baseball and umpired for 20 years.”[27] He attended a number of Negro Leagues reunions of one sort or another, and Jim and his wife frequently went to spring training in St. Petersburg.

Interestingly, James Zapp Jr. is active umpiring high school baseball into the year 2016. He had three siblings, three of whom pursued careers in the military; all three retired in the very same year, 2003.

James Jr. says: “I retired after 26 years in the Army. My rank was Sergeant Major (E9) and I was the senior medical NCO for III Corps and Fort Hood. I was a paratrooper with time in the 82nd Airborne and the Special Warfare Center at Fort Bragg. I was a paratrooper medic. My sister retired from the Navy after 21 years after being involuntarily extended for two and half years due to 9-11. She retired as a First Class Petty Officer (E6), with her job encompassing all aspects of Aviation Maintenance Administration. My brother retired after 23 years as a Chief Petty Officer (E7) and was an Independent Duty Corpsman. All of us served in Desert Storm and Desert Shield.”[28]

Jim’s wife, Viola, died in 1982 and his second wife, Muffy, died in 2013. “That’s when I went to Nashville,” James Jr. said. “We realized that he had Alzheimer’s and I got guardianship of him and brought him here.” Here being Harker Heights, Texas.

In 2014, it looked as though he was dying. The word went out to leave him in peace.

But in 2015, another chapter of Jim Zapp’s life unfolded. First, it had seemed as though he was gone, but then he came back to life.

James found accommodation for him in a senior citizens home only about five minutes away. “He is in the area that requires 24-hour care. When I first put him there, my dad was still partly there. He complained to me, ‘James, I shouldn’t be here. I’m not crazy like these people.’ Some of them were pretty bad.”

Diagnosed with stage four Alzheimer’s, the staff at the facility also experienced some problems with Jim. Around June 2014, the staff increased the medications. Jim had reported some pain, and the medications addressed it.

Then his condition appeared to deteriorate. “Every time we went to see my dad, he looked like he was comatose. He couldn’t stay awake more than 10 seconds and he would go back to sleep. They had him in one of these wheelchairs where he was laying back and he couldn’t get up. He couldn’t feed himself. He couldn’t talk. Nothing. This went on for six months, and basically my dad was nonexistent. We thought he was going. He was gone. He was basically gone.”

Until that point, Jim had routinely signed autographs by mail for those who would write in and request one. That became impossible. Around this time, SABR member Nick Diunte posted a letter from James Jr. on Nick’s Baseball Happenings website. The letter was dated January 8, 2015. It began: “Thank you for contacting me in reference to my father autographing your card. Unfortunately my father is in the final stages of Alzheimer’s, has aspirations pneumonia, and is not expected to live to reach his 91st birthday.” He added, “My father has been with me since March 2013 after losing his wife of twenty-seven years. He celebrated his ninetieth birthday on 18 April 2014. He was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s six years ago and has gradually lost his short term and much of his long-term memory. He has lived a great life.”

Clearly, James Jr. didn’t think his father was going to survive another three months, until his birthday in April 2015. But he did. In his own way, Jim Zapp fought on.

Fortunately, both James and his brother, Richmond, are medical professionals. As anyone would, they believed the doctors at the senior home were doing what needed to be done—until one day James decided to question it. “I thought, ‘This is odd. They’re giving him all these drugs. Painkillers . . . for what pain, I do not know. They’re giving him a lot of stuff. They were giving him anti-anxiety pills, clonazepam. And sleeping pills.’”

One day he called a meeting and instructed the staff that they were to take him off all medications. Even aspirin. If his father reported pain, they were to call him and he would drive over—even at 2 a.m.—and determine whether or not to give him pain medication.

“And if I’m not there,” he said, “I will call my daughter who lives with me and is 19 and still going to college and I will tell her to go down there and look at her granddad. There’s always going to be someone here.

“So they took him off the medicine. They quit giving him any medicine at all.”

James Jr. left Texas for Colorado for a couple of weeks and he was in for a shock when he returned. He went to the home for another visit.

“We couldn’t find my dad. We’re like, ‘Where’s he at?’ We finally look up and here comes my dad, in a regular wheelchair, with his feet walking and rolling down the hall. I stand in front of him and he looks up and he sees me, and he recognizes me!”

It had been over a year. “Over a year! My daughter Jayda was with me. He recognized my daughter. I immediately contacted my brother and my sister and said, ‘You guys aren’t going to believe this.’ I took a video with my phone. I sent them the video. My sister was in tears.”

Overmedication is a common problem in such facilities. “He was having some pain problems and they gave him pain medicine and they never took him off of it. I guess one thing led to another and they kept giving him more medicine. They gave him the anti-anxiety pills to help him sleep. They basically had been drugging my dad up, to stop from having to deal with him.”

Did the nurse ever call at 2 a.m. due to pain? “They told me they would call me if he was ever in any pain. That was September. It’s now almost February and they have called me one time when they said he was in pain and that was like a month ago. It was like at midnight. So I got up and I drove down there and my dad was asleep when I got there. I woke him up and he saw me and he says, ‘Hey, Baby.’ He always called us Baby. I said, ‘Daddy, are you in any pain?’ He goes, ‘No, you woke me up.’ ‘OK, good night.’ I gave him a kiss and I walked out. So all this pain medicine they were giving him, he was not in any pain.”[29]

A lot of families would never question it. Some family members aren’t able to visit very often. Most would not have the medical background to even begin to understand the possibilities. Though every situation is different, the Zapp family’s experience offers a lesson that may prove helpful to other families.

More than five months after being taken off all medication, Jim Zapp was effectively brought back to life, where he could recognize his children and granddaughter.

More than six months later, this author had the opportunity to speak with Jim Zapp briefly over the telephone on March 27, 2016. It wasn’t the time to pose difficult questions that might have taxed a memory afflicted by Alzheimer’s, but Jim introduced himself by name and recalled briefly playing for the Barons and in Hawaii with the Navy. It may have lifted his spirits to converse about some good times.

James knows it is never easy for his father. “It’s been a long road with my dad, but it’s sad. It’s very sad. My dad was always so spirited. There was never a day in my dad’s life when we were kids that he did not give us a hug and tell us he loved us. A hug and a kiss, and an ‘I love you.’ Every day. I try to do the same thing with my kids, and it seems to work.”[30]

Sources

In addition to the sources cited, the author would like to thank Jim Zapp’s three children—Jenniffer, James, and Richmond—each of whom read through the manuscript and offered suggestions for improvement.

[1] Brent Kelley, The Negro Leagues Revisited (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000), 198.

[2] James Riley, in his Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, places Zapp’s birth at Elyria, Ohio, but available census

information uniformly places him as a native of Tennessee.

[3] Author interview with James Zapp on December 30, 2015.

[4] http://www.baseballinwartime.com/negro.htm.

[5] Kelley, 197. After the war, Edgar Jones played five seasons in the NFL, one game in 1945 for the Chicago Bears and then 43 games for Paul

Brown and the Cleveland Browns from 1946 to 1949. He was a halfback and defensive back and scored 18 touchdowns for the Browns. See

http://www.pro-football-reference.com/players/J/JoneEd21.htm.

[6] James Riley, Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994), 893.

[7] http://www.baseballinwartime.com/BIWNewsletterVol7No37July2015.pdf.

[8] Kelley, 200.

[9] Both the Elite Giants and Cubs information comes from http://baseballinlivingcolor.com/player.php?card=160. Zapp told Kelley of playing weekends for the Baltimore Elite Giants.

[10] Riley, 893.

[11] Kelley, 198.

[12] Ibid., 198, 199.

[13] John Klima, Willie’s Boys (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2009), 57–58.

[14] Ibid., 183.

[15] NLBM Legacy 2000 Players’ Reunion Alumni Book (Kansas City, Mo.: Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, Inc., 2000).

[16] Zapp remembered this as in Game 3, and the score as 2–1, him homering with a man on to win the game, 3–2. See Kelley, 199. He said then

the two teams went to Kansas City, where the Barons lost three games in a row, bringing it to a decisive Game 7, which Bill Greason won, 4–1, for

Birmingham.

[17] Kelley, 199.

[18] Ibid., 193.

[19] http://baseballinlivingcolor.com/player.php?card=160.

[20] See also Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, N.C.: Baseball America, 2007), 464.

[21] NLBM Legacy 2000 Players’ Reunion Alumni Book.

[22] “MOV Loop Names All-Star Squad,” Peoria Journal-Star, September 19, 1952: 24.

[23] Kelley, 200.

[24] Email from James Zapp Jr., January 17, 2016.

[25] Kelley, 201.

[26] Riley, 894.

[27] NLBM Legacy 2000 Players’ Reunion Alumni Book.

[28] Author interview with James Zapp, Jr., December 30, 2015, and email from James Zapp Jr., January 4, 2016.

[29] Author interview with James Zapp on January 27, 2016.

[30] Author interview with James Zapp on January 27, 2016.