LEGENDS OF THE CAMERA

TheNationalPastimeMuseum.com focuses on baseball’s most influential photographers in this eight-part series. Author Larry Canale, who wrote two books with legendary lensman Ozzie Sweet, is your tour guide.

Part 2: Carl Horner

If you follow the music, you know the phrase “one-hit wonder”: a recording artist who charted one huge Top 40 hit and then faded to oblivion. There’s Pilot (1975’s “Magic”), and Terry Jacks (1974’s “Seasons in the Sun”), and Edison Lighthouse (1970’s “Love Grows Where My Rosemary Goes”), to name just three among thousands.

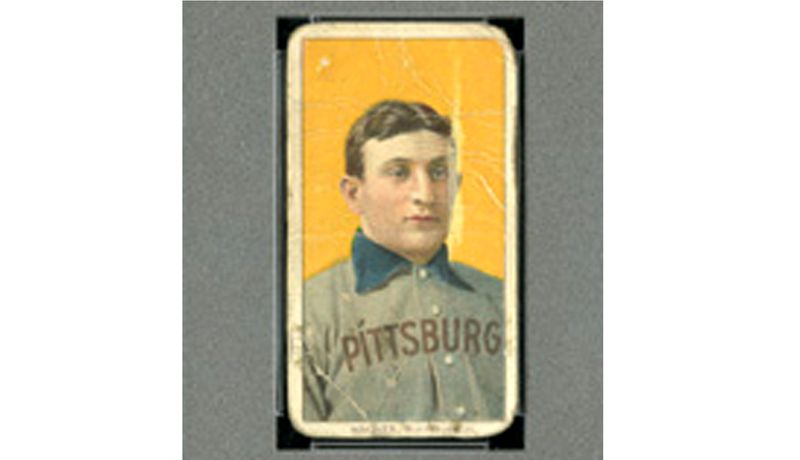

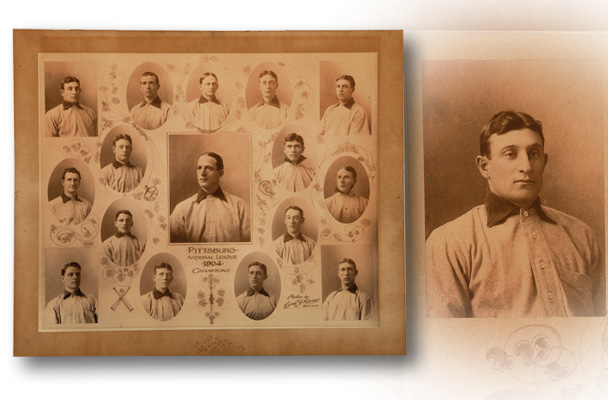

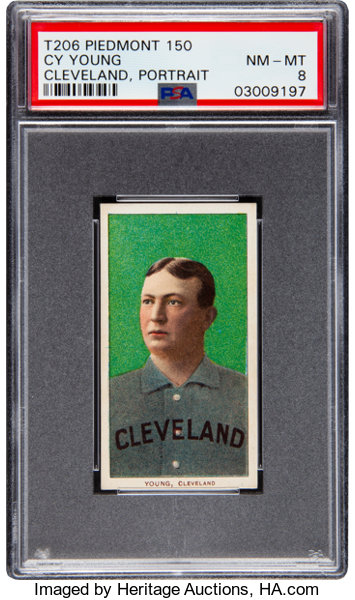

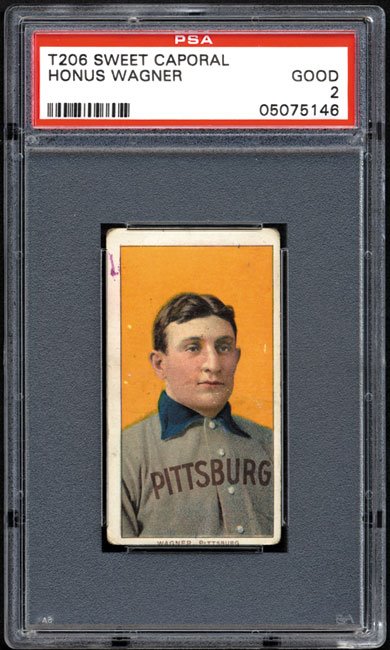

In the world of baseball, photographer Carl Horner is known for his landmark portrait of Honus Wagner—yes, that portrait: the one that appears on the most famous baseball card ever. Wagner’s T206 tobacco card pops up in the news every so often when a decent-condition example sells for a seven-figure price. Originally issued in limited quantities as a cigarette-pack premium between the years 1909 and 1911, it’s long been the Holy Grail among baseball collectors.

Wagner’s photographer, however, was no one-hit wonder. The Swedish-born Horner (1864–1926) was a productive portrait specialist who arrived in Boston in the 1880s and quickly established a studio where he welcomed a steady stream of clients—including early professional ballplayers.

Right Place, Right Time

Horner’s timing was impeccable because the 1880s marked a turning point in the evolution of our National Pastime. There are earlier references in America, of course, to “base ball.” In 1791, a Pittsfield, Mass., ordinance banned the game from being played too close to the town’s meetinghouse. In 1845, Alexander Cartwright documented the first set of rules defining the modern game. In the 1850s, various publications called baseball “the national game.” And in 1876, the National League formed.

So by the 1880s, the stars were aligned, and baseball was poised to catch on. Several professional leagues sprouted up, and as the 1890s rolled along, America was paying closer attention to teams and players.

In 1901, the NL—having emerged as the strongest professional circuit—was joined by the American League. Both the NL and AL had franchises in Boston, so Carl Horner was in a good place. Baseball needed to put faces with the names that dotted Major League rosters, and Horner delivered, working at a steady pace in creating high-quality portraits.

Also Check: 8 Best Slowpitch Softbal Bats

Horner found ready outlets for his work. “In the early 1900s,” according to baseball historian David Cycleback, “Horner’s stoic, some will say bland, portraits of Major League Baseball players were commonly reprinted by newspapers, magazines, board games, and trading cards.”

Note the use of the word “bland” in that quote. It might sound critical, but there’s no question that Horner had his subjects play it straight. Most of his portraits were serious studies rather than playful poses, expressionless gazes instead of beaming smiles.

No matter. Horner’s portraits are also incredible. He was technically adept, so his work generally shows sharp focus, lots of detail, sensible lighting, and interesting shadows. In an era when photography was neither quick nor simple, Horner gave future generations the chance to “know” hoards of famous and not-so-famous players.

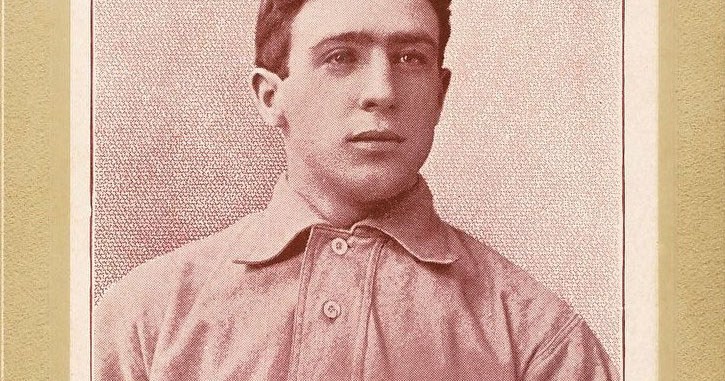

His work, in fact, helped define the look of early tobacco and candy cards. A great number of the photos used in highly collectible issues like Breisch-Williams’ 1903–04 set, American Caramel’s 1910 set (catalogued as E90-2), and Cracker Jack’s 1914–15 set (E145), among many others, had healthy doses of Horner portraits.

Personal Points

As a fan of baseball history and photography, I find myself drawn to Horner’s high-impact images. His portraits come off as classic, clean, and maybe a bit haunting. Examples? I’d point to the following as prototypical.

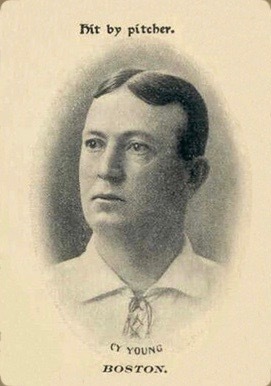

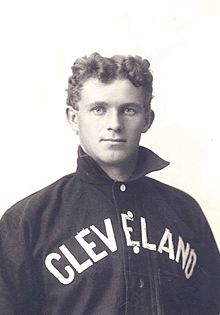

For starters, look at the portrait Horner took of Cy Young during the pitcher’s time with the Boston Americans (1901–02) before the franchise adopted the nickname Pilgrims (1903) and Red Sox (1908). Horner’s portrait captures the rubber-armed hurler in his mid-30s. By then, Young had thrown 4,043 innings and 418 complete games in just 11 seasons for the Cleveland Spiders (1890–98) and St. Louis Perfectos/Cardinals (1899–1900), so we’ll forgive him if he looks a bit tired, per the telltale bags under his eyes.

Photo courtesy of Memory Lane Inc.

Yet there’s a reason baseball named its top award for pitchers after Cy Young: He went on to pitch 12 more seasons, throw 3,313 more innings, and toss 331 more complete games. His lifetime totals (7,356 innings and 749 complete games, not to mention his 511–316 won-lost record and 2.63 ERA) are testaments to his durability and excellence. And this image of Young is a testament to Horner’s deft work with a camera. (An original cabinet-card print of this stunning image went into a current Memory Lane auction with a $3,000 minimum bid.)

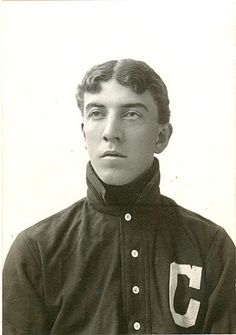

Also look at Horner’s portrait of young Tris Speaker early in his Red Sox career (the outfielder played for Boston from 1907 to 1915 before moving to the Indians). A beautifully preserved cabinet card of this rare image in near-mint condition sold for $13,375 at auction in 2007.

Most of us have seen Speaker photographs from later in his career; his hair turned silver at an early age, which figured into the nickname he picked up: The Grey Eagle. So it’s a treat to see Speaker’s youthfulness; there’s a confidence in his eyes that tells us he knew he was good. Two decades later, when he retired at age 40 in 1928, the numbers showed he was right: a .345 career average, 3,514 hits, and 436 stolen bases.

Collectors likely have seen Horner’s early 1900s portrait of the ill-fated Addie Joss. The young pitcher cast what looks like an unhappy, intense gaze past Horner in a photograph that appeared in a number of early baseball card series. Joss would play 10 seasons, post an ERA of 1.89 (second best in baseball history), and win 160 games vs. only 97 losses. But in 1911, at age 31, he died of tubercular meningitis.

Photo courtesy of Legendary Auctions

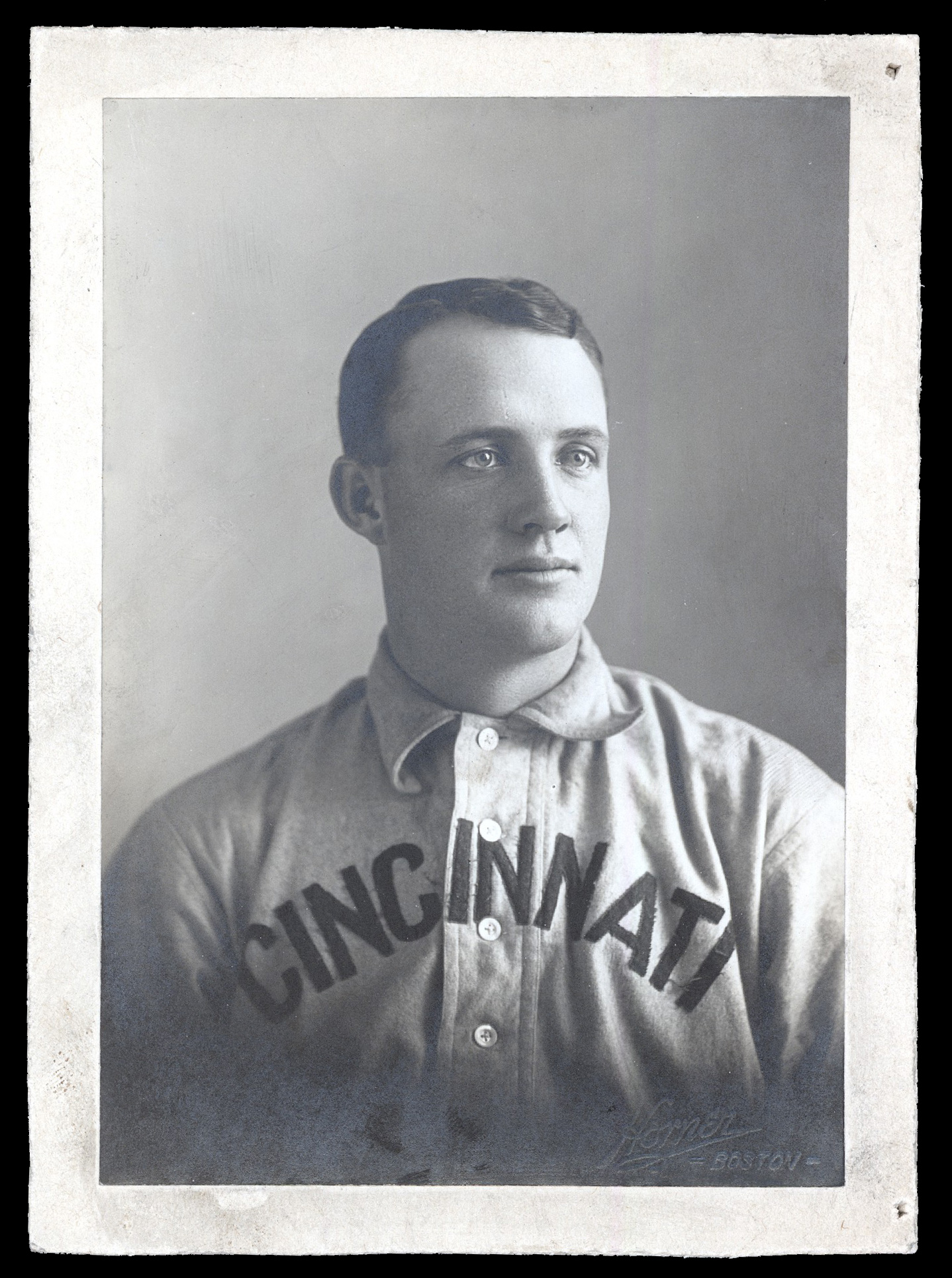

Among many other early stars who sat for Horner was Orval Overall. He may not be a household name today, but in his day, the 6-foot-2, 215-pound Overall was a star for several seasons with the Reds and Cubs, registering a 2.23 ERA (eighth best in Major League history) and a 108–71 record. Horner photographed Overall (one collar up, one collar down) during his rookie season, 1905, and produced an amazingly sharp photograph with impressive depth of field.

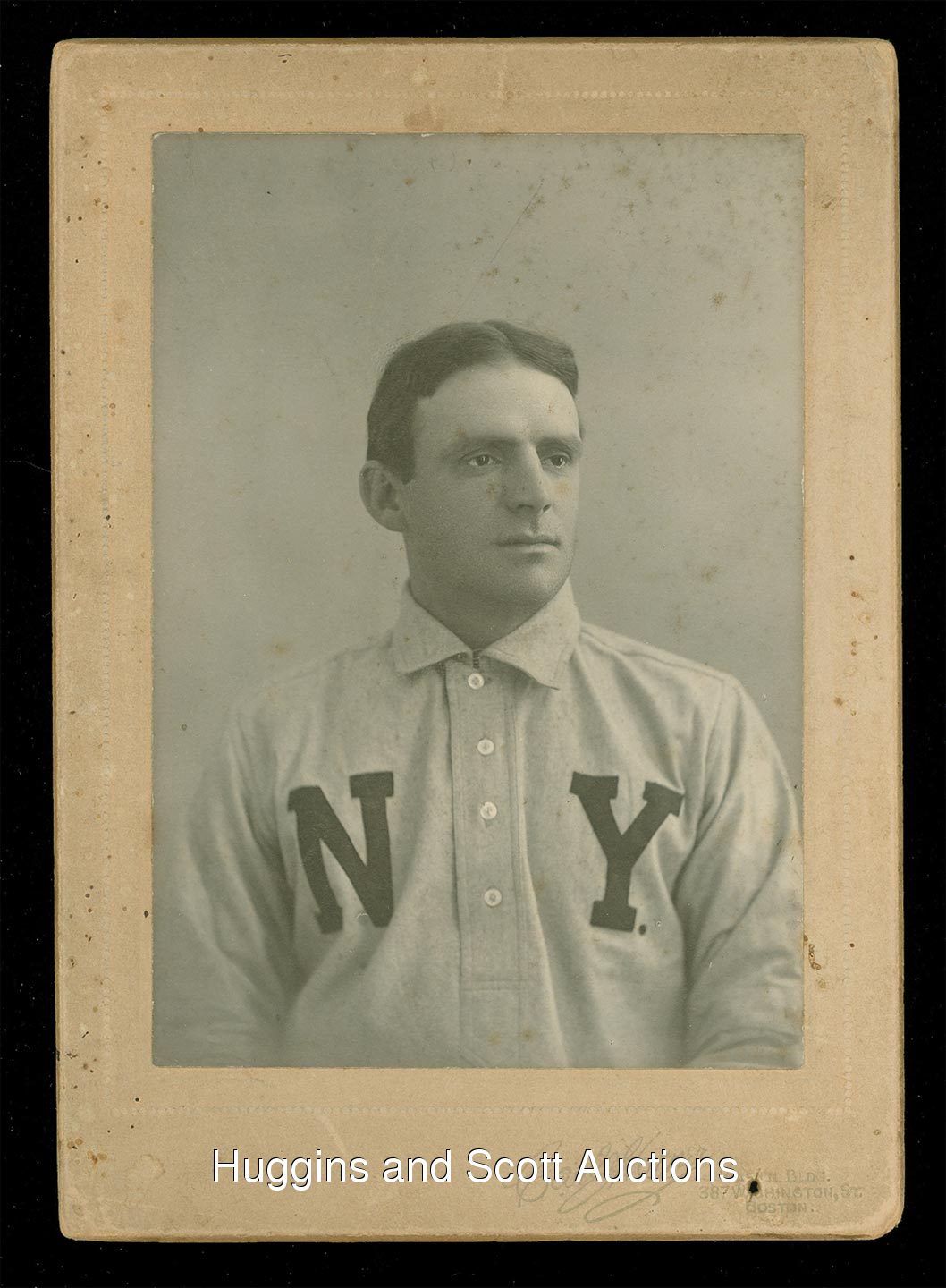

Horner created revealing portraits not only of stars but of “commons” who played under the radar. Consider Otto Hess, a Swiss-born pitcher who spent parts of 10 seasons in the bigs. While playing for the Cleveland Bronchos/Naps (1902 and 1904–08) and the Boston Braves (1912–15), Hess recorded a lifetime mark of 70–90. Wildness was both a weapon (lifetime ERA: an impressive 2.98) and his downfall (he hit 83 batters, threw 38 wild pitches, and walked 448 in 1,418 innings). He was at his most effective in 1906, when he posted a 20–17 record and a 1.83 ERA.

Photo courtesy of Mile High Card Co.

Horner photographed Hess in the early 1900s. A memorable portrait from the sitting sold at Mile High Card Co. for $1,800.

I could go on all day with examples of Horner’s work. After all, his distinctive portraits have immortalized—for fans motivated to dig deep—names that otherwise have been long forgotten.

There’s Kitty Bransfield, a first baseman who batted .270 over 12 seasons but also epitomized the “Deadball Era” by hitting 13 homers over 12 seasons. You might not get the impression by looking at Horner’s portrait of a somewhat sullen Bransfield, but he was “probably the most popular player in the National League,” according to publisher Alfred H. Spink.

There’s Kid Elberfeld, a .271 hitter over 14 years who looks mild-mannered enough in his Horner portrait but was nicknamed “The Tabasco Kid” because of his hot temper.

There’s Sammy Strang, a journeyman infielder who batted .269 while playing for five franchises over 10 seasons (and who gave Horner a “weight of the world” look).

There’s Bris Lord, who played eight years and hit .256 while earning the mysterious nickname “The Human Eyeball.”

Before this gets out of control, let’s wrap up our discussion with one more Horner subject: the obvious one. His classic Honus Wagner photograph, created a few years into the twentieth century, illustrates the Pirates’ all-world shortstop in a way that is consistent with the photographer’s style. He’s looking slightly away, his eyes gazing not into the camera’s lens but into the distance, and the expression on his face is decidedly deadpan.

The high selling prices of Wagner’s T206 tobacco card accounts for the photograph’s celebrity. But by itself, apart from the tobacco card, Horner’s Wagner portrait is an important piece of baseball history: a moment in time when Wagner was just beginning his ascent into baseball’s upper echelon.

Photo courtesy of Robert Edward Auctions