Was It Racism, Just a Bad Deal, or Better Than It Looked?

The May 1966 trade of San Francisco first baseman Orlando Cepeda to the Cardinals for pitcher Ray Sadecki is generally ranked with that of Lou Brock for Ernie Broglio, Frank Robinson for Milt Pappas, and Babe Ruth forNo, No, Nanette as one of the most lopsided deals in baseball history. The Cards won the World Series the next year, with Cepeda, their inspirational leader in the clubhouse, capturing the NL MVP Award. They also won the pennant in 1968, while the Giants, despite all their talent, finished second both years. Sadecki spent the rest of his career as a journeyman pitcher who never won more than 12 games in a season.

On the surface it seemed as if St. Louis scored a coup, and many thought the apparently uneven exchange had been initiated because the Giants thought they had too many minorities on their team. In 1964, San Francisco Manager Alvin Dark, thinking he was off the record, told Newsday sportswriter Stan Isaacs that he believed one of the reasons his team was underachieving was that the Giants had too many blacks and Latinos, whom Dark said were not team players and not adept at the mental aspects of the game.

Remarks like that are often made after a few drinks, but Dark was a teetotaler. He knew what he was saying, and he meant it. Isaacs printed Dark’s comments, which unleashed a firestorm, and it was foreordained that he would be fired after the season. Even though Dark was gone by 1966, his legacy remained, and the chemistry in the San Francisco clubhouse was edgy. Cepeda was one of the malcontents.

The Giants had a mixed legacy on race. In the early days of integration, the club was a leader in signing African-Americans, and their 1954 world champions featured Willie Mays, Monte Irvin, and Hank Thompson. Manager Leo Durocher was progressive in his attitudes toward blacks and almost a surrogate father to Mays. On the down side was the legacy of Dark, a son of the Deep South who polarized the locker room with his 1964 remarks. When the Giants traded star outfielder Felipe Alou after the 1963 season, many thought the purpose was to reduce the number of Latinos on the roster.

Also Read: Best Wood bats

Did the Giants get rid of Cepeda because he was a Latino, or was there a logical reason to send him to St. Louis? Was the trade as bad as it seemed for the Giants, either at the time or in retrospect?

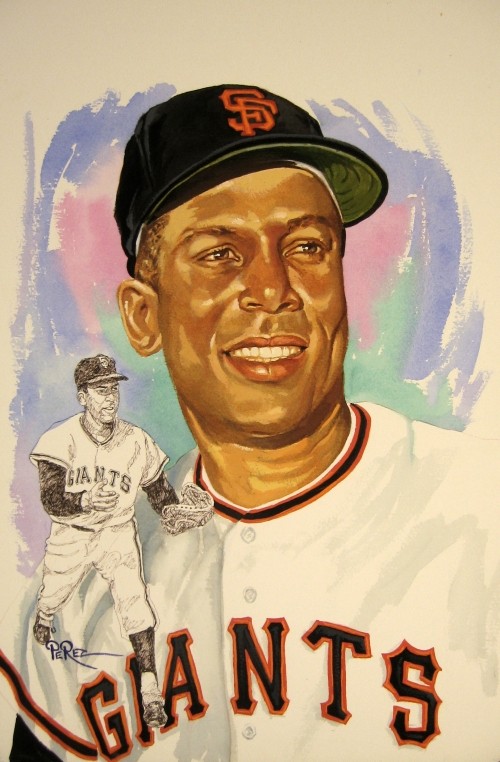

In 1966, Cepeda was 28 and in his baseball prime. He had been a star in San Francisco, hitting 222 home runs during his first seven seasons and never batting less than .297. There were, however, two factors that made Cepeda expendable. The first was the serious 1965 knee injury that required surgery and limited him to 34 at-bats that year. Cepeda’s knees would bother him for the remainder of his career, limiting him to designated hitting duties his last two years. After age 32, he played less than 100 games in the field and missed large portions of the 1971 and 1972 seasons. Give the Giants credit for recognizing the severity of Cepeda’s injury and the probability that it would shorten his career.

A second reason to trade Cepeda was the fact that the Giants had another pretty fair player whose natural position was first base. He was Willie McCovey, whose 521 home runs would earn him a place in the Hall of Fame. When Cepeda missed nearly all of the 1965 season, McCovey took his place at first base and hit 39 home runs.

For several years, Cepeda and McCovey had divided time at first base and left field, with Cepeda getting the majority of the time at first. When Cepeda returned in 1966, McCovey went back to the outfield, where he was a marginal fielder at best and a major defensive liability at his worst.

By 1966, it was becoming increasingly difficult to keep McCovey in left field, because Willie Mays was 35, and his range was diminishing. He needed someone more nimble than McCovey on his flank to get the balls he could no longer reach. The Giants had a 20-year-old power-hitting speedster named Bobby Bonds at Fresno, just two years away from playing in the Giants outfield. If Cepeda remained at first and McCovey in the outfield, there was no room for Bonds. In addition, the Giants had promising youngsters like Ollie Brown and Jesus Alou, who, like McCovey and Bonds, were minorities. The Giants did not trade Cepeda to replace him with a mediocre white player.

If either Cepeda or McCovey had to go, the Giants’ decision to keep McCovey was the correct one. He was the 1969 NL MVP, his career statistics far eclipsed those of Cepeda, and he played six years longer than the latter, who would have been out of baseball even sooner were it not for the designated hitter rule, which was not in effect in 1966.

Cepeda was a leader in St. Louis and, along with Bob Gibson, one of the biggest reasons for the strong chemistry in the Cardinal clubhouse. But he had not been a leader in San Francisco, and it was unlikely he would have become one, for he had not been happy with the Giants, where Dark’s statements had created a negative atmosphere among all the minorities on the team.

While there were valid reasons to trade Cepeda, he had significant market value, despite his damaged knee. Could the Giants have done better than Ray Sadecki? When judging trades that turned out badly, one must look at the situation at the time the trade was made, rather than with the hindsight of several decades. Ruth, with his sour attitude in his final Boston season, put the Red Sox in a position where it would have been almost impossible to bring him back for another year. Brock was a young player with power, speed, and potential who struck out a lot and made a lot of errors, while Broglio was an established Major League pitcher. Could the Cubs have foreseen that Broglio would suffer a career-ending arm injury?

In 1966, Sadecki was a talented 25-year-old left-hander who had won 20 games just two years earlier. When the trade was announced, former Cardinal legend Dizzy Dean said he thought the Giants had just assured themselves of the pennant. The Giants seemingly had a surplus of hitters, certainly a surplus of Hall of Fame first basemen, but their Achilles Heel throughout the 1960s was pitching depth. Trading from a surplus to shore up a weakness is a time-honored baseball strategy, particularly when quality replacements are in the wings. While the Giants expected more of Sadecki, he was a serviceable pitcher still playing in the big leagues in 1977, three years after Cepeda played his last game.

What is the final verdict? In the short run, the Cardinals got the better end of the bargain. They reached the World Series in Cepeda’s first two years and won once. Cepeda won an MVP title. It can be argued, however, that the Giants had no choice but to trade either McCovey or Cepeda, and they clearly picked the right one. If young pitchers like Nelson Briles, Dick Hughes, and Steve Carlton hadn’t stepped up to replace Sadecki, the Cardinals wouldn’t have won any pennants. And if Sadecki had won 20 games for the Giants, like he did with the Cards, the World Series might have been played in San Francisco instead of St. Louis.

Even with the benefit of hindsight, the trade was not as one-sided as it is often portrayed. While there was clearly a personality issue, it may not have been racial, and the final result could have been different if the stars had aligned differently for the two teams. Could the Giants have obtained more for a future Hall of Famer? Who knows? That’s why it’s easier to be a historian writing with 50 years of perspective than a general manager trading a star player.