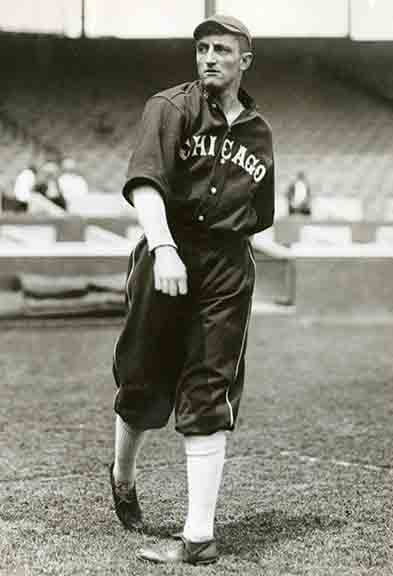

In 1935, Lena Blackburne—one-time-phenom-shortstop-turned-utility-infielder-turned-coach-turned-manager-turned-coach again—was described by The Sporting News, 16 years after his playing career ended, in the only terms that mattered to the historical record. Never mind that he was “intelligent,” “industrious” and “a fighter,” all of which the newspaper took care to note. No, the most important facet of the man’s game was summarized in a tidy 11 words: “No matter where baseball gods have sent him, he has hustled.”[1]

Hustling was what Blackburne did best. It’s why a guy with all those hyphens ended up batting only .214 as a big leaguer, yet still managed to string out his career until age 32. It’s also why in modern times, he’s remembered primarily for mud. That’s Blackburne’s name attached to the Delaware River goop shipped to big league clubhouses across the country, used for rubbing up new baseballs to remove the sheen and improve pitchers’ grips.

Lena Blackburne’s Rubbing Mud isn’t exactly a secret—it’s been in wide use since 1938 and can be purchased through the company website in sizes as small as a half pound. Its story, however, and that of Blackburne himself, have garnered far less attention.

His given name was Russell, a detail that was all but forgotten after a game during his first minor league stop, at Worcester, Mass., in 1908. The lineup of Brockton, that day’s opponent, included an outfielder named Cora Donovan, inspiring one fan to heckle after Blackburne struck out, “Hey, Lena, you any relation to Cora?” The taunt stuck so pervasively that even Blackburne’s wife took to calling him Lena. (Rarely mentioned was that the man who signed Blackburne to his first minor league deal, and under whom he spent 13 of his 17 big league seasons as a coach, was the femininely named Connie Mack.)

Blackburne quickly became the Eastern League’s best-fielding shortstop, and scouts descended … until word got out about Blackburne’s “cheaters,” or eyeglasses, which he wore away from the field—news likely leaked by one of the bidding clubs to drive his price down. Nonetheless, White Sox owner Charles Comiskey paid $8,500, plus two minor leaguers, for the player’s contract.

The idea was for Blackburne to become the missing piece for an otherwise-stout White Sox infield, but the shortstop played in fewer than half the team’s games in 1910, batting .174. A leg injury cost Blackburne the entire 1911 season and part of 1912 and began a journeyman trek through the Northeast in which he alternated minor league stints with trips back to Chicago, then on to Cincinnati, Boston, and Philadelphia. Blackburne was finished as a big leaguer in 1919 at age 32, having played nearly three times as many minor league games as Major League ones.

Blackburne continued as a minor league player and part-time manager until getting hired as a White Sox coach in 1927. He was promoted to manager midway through the 1928 season, his teams going an ignominious 99–133 until his firing in 1929. Blackburne’s most noteworthy moment involved getting into a fistfight with one of his players, Art Shires, in a hotel room in Philadelphia, the match garnering special attention when it was learned that Shires single-handedly took on Blackburne, the team’s traveling secretary, Lou Barbour, and two hotel security guards.

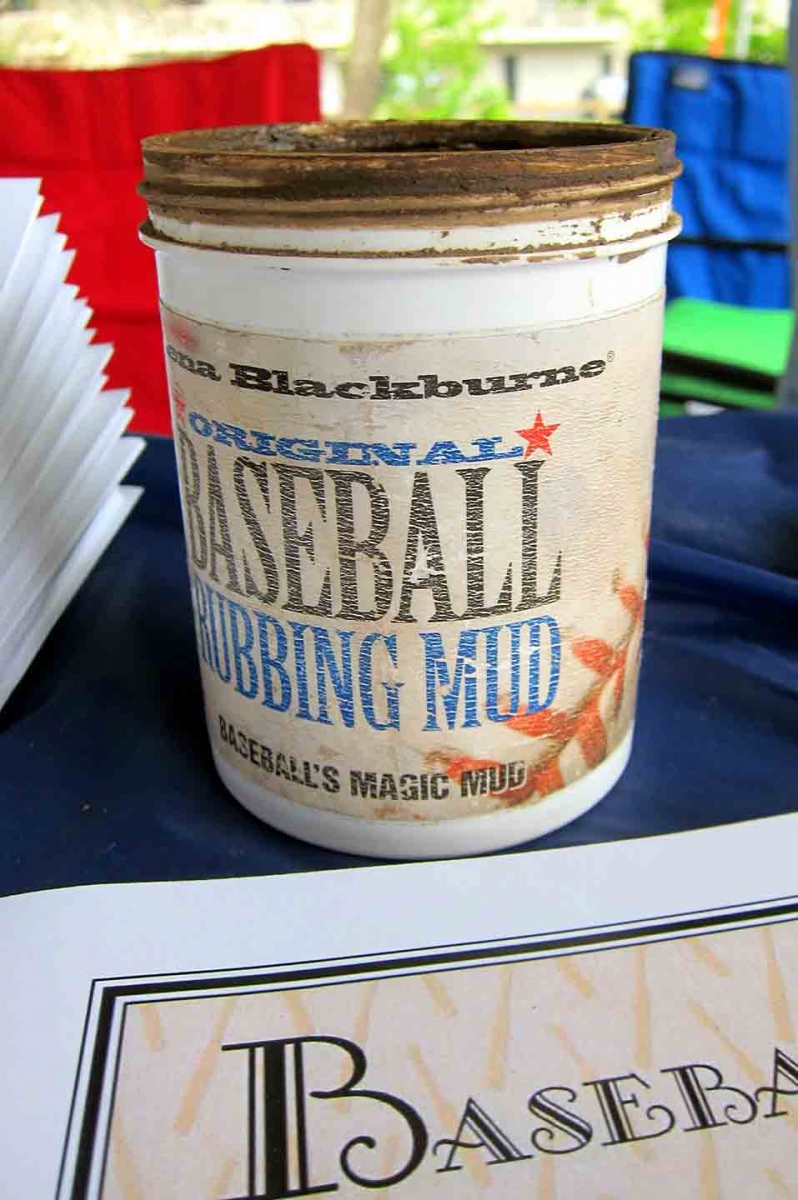

It wasn’t until Blackburne signed on with Mack’s Athletics in 1930 that his legacy was cemented in mud.

It happened during a game in 1938. Blackburne was coaching third base when he overheard umpire Harry Geisel bemoaning the task of rubbing up the baseballs. The concoctions umpires used for the job were hardly standard, with the primary substances of choice—random assortments of tobacco juice and infield dirt—proving to be both insufficient and disgusting. Tobacco left unseemly stains on the ball. Mud softened the cover and tended to cake into the seams.

Blackburne thought of something better. He had grown up alongside the Delaware River in Palmyra, New Jersey, some 20 miles outside Philadelphia. It was while wading in one of the river’s feeders, Pennsauken Creek, as a kid that he discovered a spectacular form of mud during low tide. Looking back, Blackburne theorized that the outgoing water “purified the mud at the bottom of the creek, leaving it inky black and sticky.”[2] It didn’t take long for him to recognize the utility of the stuff, and he packed it up for rubbing purposes every time his youth league team was able to acquire a new baseball.

When he heard Geisel’s complaints, the mud of Blackburne’s boyhood came immediately to mind. In short order, he drove back to Pennsauken Creek and retrieved a bucketful. Then he set to experimenting.

What Blackburne ended up doing to the mud is still a closely held secret by his corporate heirs—as is the precise location of the stash—but, man, did it work. It was smooth and easy to apply and left virtually no residue or odor while providing the perfect amount of tack. (The closest Blackburne came to disclosing his secret spot was in a 1965 interview in which he claimed the location to be at the intersection of two streams, leaving the mud “filtered twice and very fine.”[3])

The following spring, Blackburne delivered a can of the goop to Geisel, who was immediately enamored. Word soon spread, and before long Blackburne had a side business filling orders from every American League club. He insisted on keeping the price low, intoning that his operation was less business than a hobby. For many years, he shipped the stuff in discarded coffee cans collected for him by Father William Quinn’s Sacred Heart rectory. Even today, a season’s supply of Blackburne’s compound can be had for less than $100.

The phrase “your name is mud” is an age-old insult, but in at least one instance there can be no higher compliment.

[1] The Sporting News, December 5, 1935.

[2] The Sporting News, March 16, 1968.

[3] Family Weekly, September 5, 1965.