Award-winning sportswriter Ring Lardner was one of the greatest humorists of the early twentieth century. Beat writer, columnist, essayist, and short-story writer as well as poet, playwright, music lyricist, and (briefly) comic-strip author, Lardner’s favorite subject was baseball. Pomrenke concludes his series by describing how Lardner used the game and its many colorful characters to shed light on the absurdity of life in the Major Leagues.

In baseball, it’s important to have a healthy sense of humor. In a sport where even the best hitters fail seven out of every 10 times at bat, how else can anyone survive the long, grueling season without a little laughter along the way?

There is no shortage of amusing stories, and we all have our favorites. Blooper reels have long been a scoreboard staple between innings at a ball game, from Rick Dempsey’s rain-delay antics to the fly ball bouncing off Jose Canseco’s head for a home run. Players like Adrian Beltre and Bartolo Colon have endeared themselves to a new generation of fans thanks to an endless supply of entertaining Internet clips. Joe Garagiola, the catcher turned broadcaster and TV star, titled his best-selling first book Baseball Is a Funny Game for good reason.

And the godfather of baseball humor, a literary phenom who continues to make fans laugh more than one hundred years after his first story was published, is a man with a funny name: Ringgold Wilmer Lardner.

Ring Lardner was one of America’s greatest humorists. He was a master of vernacular literature, a sharp but cynical satirist who focused on stories about the “common man.�? But his favorite subject was baseball, and he used the game and its many colorful characters to shed light on the absurdity of life in the Major Leagues. He wasn’t the first baseball writer to use comedy to illustrate his stories, but Ring Lardner made comic sportswriting an art form like no one before or since. Lardner was the first baseball writer to be selected as a recipient of the J. G. Taylor Spink Award after Spink himself, receiving the honor posthumously in 1963.

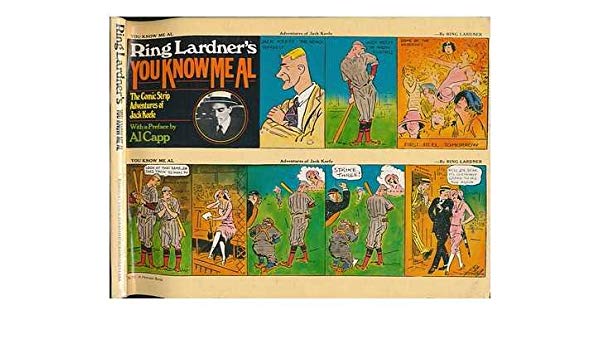

It’s virtually impossible to find a modern-day comparison for the versatile Lardner. He was at times a beat writer, a columnist, an essayist, and a short-story writer—also a poet, a playwright, a music lyricist, and (briefly) a comic-strip author. He enjoyed some level of success in just about all of those mediums, with an ear for dialogue that earned him critical praise from the likes of H. L. Mencken and Virginia Woolf. He was compared favorably to Mark Twain and was admired by Ernest Hemingway, who was said to have chosen the pseudonym “Ring Lardner Jr.�? as a byline for his high school newspaper. (Lardner’s son, the real Ring Lardner Jr., became an Oscar-winning screenwriter.)

Lardner was recognized as one of the most famous writers in the nation during his prime, but unlike the renown of his drinking buddy and one-time neighbor F. Scott Fitzgerald, Lardner’s fame proved fleeting. Although several collections of Lardner’s stories have been published, he is rarely read today because most of his best writing is still buried in the dusty archives of the newspapers and magazines where his byline appeared. He never wrote a timeless novel like The Great Gatsby or The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the type of book taught in high school English classes for years afterward. He just cranked out funny stories and memorable characters, day after day.

His friends and critics, aware of his boundless talent and keen insight into the American experience, encouraged him to write his own version of the Great American Novel, to secure his reputation as a literary and comedic genius. But Lardner resisted, preferring to write lucrative short stories that he could sell to magazines and syndicated columns about the events and people that surrounded him. Because so much of what he wrote was topical, his work hasn’t aged as well as Fitzgerald’s or Twain’s. The inside jokes and had-to-be-there moments that captivated audiences in the early twentieth century aren’t so readily translated by readers in the twenty-first.

Fitzgerald himself blamed Lardner’s love of baseball for his unrealized greatness, criticizing his friend’s favorite subject matter as “a boy’s game with no more possibilities in it than a boy could master, a game bound by walls which kept out novelty or danger or adventure. However deeply Ring might cut into it, his cake had the diameter of Frank Chance’s diamond.�? But if baseball was not a serious topic for a serious writer (as Fitzgerald claimed), it’s nonetheless the biggest reason Lardner is remembered today. He infused the National Pastime with a literary flair that delighted millions of readers and made a lasting impact on the sport.

His influence can be felt in Jim Bouton’s classic Ball Four, arguably the most entertaining baseball book ever written. Bouton’s collection of candid and occasionally raunchy diary entries stirred up controversy because he treated star athletes like Mickey Mantle not as infallible heroes but as flawed, complicated human beings who happened to be good at baseball. A half-century earlier, Lardner was breaking those same barriers, offering fans a rare glimpse at how ballplayers lived outside the white lines in his epistolary novel You Know Me Al (1914). Lardner’s protagonist, the fictional White Sox pitcher Jack Keefe, is an egotistical rube who is often played for a fool by the worldly real-life Major Leaguers with whom he interacts. Lardner knew those players well and based some of Keefe’s misadventures on what he had seen and heard as a beat writer at the Chicago Tribune.

Lardner’s deconstruction of ballplayers as idealized folk heroes was a regular feature in his newspaper columns, where he liked to lampoon the day-to-day activities of the White Sox and Cubs players he covered in the 1910s. He had fun with their foibles, playfully mocking their superstitions or prominent physical features. One of his favorites was Cubs outfielder Frank “Wildfire�? Schulte, a colorful figure sometimes said to be the inspiration for Jack Keefe. Schulte’s antics was an ongoing source of amusement in Lardner’s stories, which delighted Schulte and his teammates just as much as they did the writer and his fans.

Lardner also used humor to shed light on the influence of money in professional baseball. One of the recurring themes of the Jack Keefe stories—his final story was published in 1919, several years after the release of You Know Me Al—is Keefe’s self-delusion as he attempts, and fails, to negotiate a higher salary from White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, who was portrayed accurately by Lardner as an owner who took advantage of the reserve clause but didn’t go out of his way to pay players poorly. Lardner’s short story “The Hold-Out,�? written for the Saturday Evening Post, also explores what little leverage players had to ask for more money in that era before free agency. Decades before the business of baseball was regularly covered in the press, Lardner was making astute observations about these behind-the-scenes issues.

One of Lardner’s most incisive commentaries about the business of baseball appeared in his Chicago Tribune column in December 1914, after future Hall of Famer Eddie Collins was sold by the Philadelphia Athletics to the White Sox for the princely sum of $50,000. The rise of the upstart Federal League had team owners complaining about rising salaries and the supposed disloyalty of players who jumped contracts to join the new league. But in most cases, the owners chose to bite the bullet and pay their star players what they were worth. Connie Mack went to the other extreme and decided to dismantle the A’s dynasty, which had won four of the last five American League pennants, and sell off all of his top talent. Lardner generally respected the men who ran Major League teams and didn’t question their decisions, but he also suffered no fools. Mack’s justification for his “fire sale�? must have offended the writer’s sensibilities, because on the day the Collins deal was struck he wrote this sardonic verse:

Players who jump for the dough

Bandits and crooks everyone.

Baseball’s a pleasure you know

Players should play for the fun.

Magnates don’t care for the money.

They can’t be tempted with gold.

They’re in the game for the fun—

That is why Collins was sold.

Lardner’s attitude suggests he was well aware that the owners weren’t as altruistic about baseball as they liked to portray themselves, and that they cared as deeply about their personal finances as the players did about their own. His understanding and acceptance of the financial trappings of the National Pastime ought to help dispel another old myth that has shaped Lardner’s legacy. Many critics have written that Lardner became so disillusioned by the Black Sox Scandal that “he never recovered,�? or that he stopped writing about baseball entirely after the 1919 World Series. This is demonstrably false.

While it’s true that Lardner’s baseball output diminished considerably after 1919, that had more to do with the fact that he left his job as a sportswriter at the Chicago Tribune that summer and moved to New York to become a columnist for the Bell News Syndicate, where he wrote on a wide variety of subjects, including baseball. One of his first assignments for Bell was to cover the World Series between the White Sox and the Cincinnati Reds, and he continued to cover the Fall Classic for Bell throughout the 1920s. During the 1927 World Series, which was broadcast on radio by Graham McNamee, he took a jab at the famous broadcaster known for his malapropisms: “There was a doubleheader yesterday: the game that was played and the one McNamee announced.�?

Historian Leverett T. Smith has argued that Lardner’s relative lack of enthusiasm toward baseball later in his life stemmed from his disinterest in the home run–happy style of play epitomized by Babe Ruth. Lardner had grown up in the Deadball Era and, as a traveling beat writer, had been especially close to the players who came of age then, too. As early as 1921—a year when Ruth was breaking his own single-season record with 59 home runs for the Yankees—Lardner expressed this feeling (in his trademark slang):

It ain’t the old game which I have lost interest in, but it is the game which the magnates have fixed up to please the public in their usual good judgment. A couple of yrs. ago a ball player named Baby Ruth that was a pitcher by birth was made into an outfielder on acct. of how he could bust them . . . and the masterminds that control baseball says to themselves that if it is home runs that the public wants to see, why to leave us to give them home runs.

Years later, Lardner wrote a letter to New York Giants Manager John McGraw in which he confessed, “Baseball hasn’t meant much to me since the introduction of the TNT ball. . . . [It] robbed the game of the features I used to like best.�?

Lardner was a man of his time, for better or worse. But no writer captured that time, and all the people in it, better than he did. It is through his stories and articles that we gain a great—and often hilarious—understanding of life in the early twentieth century, in the tumultuous days before and during World War I. Baseball, was at the heart of American life then, and Lardner was the one measuring the beats.

Image source: Library of Congress Photographs & Prints Online Cataglog