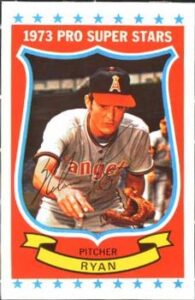

Bob Klapisch remembers the extraordinary career of pitcher Nolan Ryan—whose strong but inconsistent performance with the team that drafted him led to one of the most regretted trades in baseball history—when the New York Mets traded Ryan to the California Angels for Jim Fregosi in 1971.

Courtesy: The Trading Card Database

There was a three-hour time difference that separated me and Tom Seaver; breakfast was just finishing back east, which meant it was inhumanly early in northern California where The Franchise was calling from. But we were working on Seaver’s schedule, not mine. Who was I to contest the starting time of our conversation about Nolan Ryan.

“Such an unbelievable arm,” Seaver recalled. “I always felt that Nolan had the ability to throw a no-hitter every time he stepped on the mound. How many pitchers could you say that about in the history of the game? Hitters hated getting into the batter’s box against him, they dreaded it. But we never knew what we were getting from Nolan on any particular day.”

Even at that hour and decades after the fact—our phone call took place 40-plus years after Seaver and Ryan had been teammates—the memory bank was still full. Seaver had not forgotten how highly the New York Mets thought of Ryan, or the reason the organization finally traded him in 1971.

The entirety of Ryan’s career has been scrutinized, analyzed, and archived by now. Generations of baseball historians have come to appreciate his otherworldly fastball, his ability to mow down opposing lineups at will, and the uncanny war he waged with nature. Ryan was throwing that fastball in the upper 90s well past his 40th birthday. Few hurlers could keep up with him Not even the great Seaver could match Ryan’s forever-young genes.

But those early years with the Mets were a billboard of inconsistency; for every masterpiece Ryan threw, he was sabotaged by a maddening wild streak. That incredible velocity came with a predictable surcharge—walks.

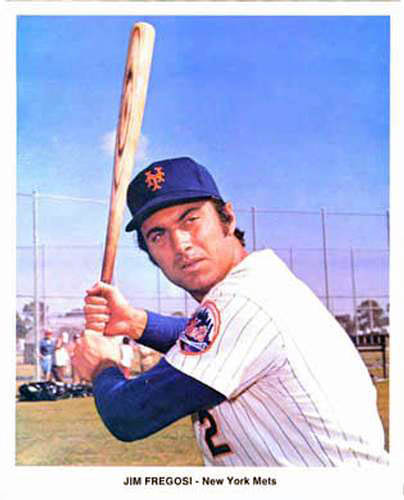

The Mets waited four full seasons for Ryan to blossom before finally giving up. They traded him to the Angels for Jim Fregosi on December 10, 1971, fully aware of the risk. History had already taught the industry that hard throwers cursed by wildness don’t always flame out. Case in point: Sandy Koufax, who staggered through five years as a .500 pitcher until he finally cracked the code to success. But the Los Angeles Dodgers surely had their moments of doubt, especially in 1958, when the 22-year-old Koufax issued 105 walks in 158 innings and led the Majors with 17 wild pitches.

But while the Dodgers decided to invest in Koufax for the long haul, the Mets had other ideas for Ryan. He hadn’t pitched poorly—a 3.58 ERA and 8.7 strikeouts per nine innings during his tenure at Shea Stadium—but as General Manager Bob Scheffing said, “[Ryan] just hasn’t done it. How long can you wait?”

Courtesy: The Trading Card Database.com

The acquisition of Fregosi was in retrospect an even bigger gamble. He’d put up six All-Star seasons in his 11 years with the Anaheim Angels, but hit a career-low .233 in 1971. The Mets dismissed Fregosi’s struggle as merely a prolonged slump—there was no reason to believe his decline phase was beginning at age 30. Yet, Fregosi’s numbers proved exactly that; his best years were already behind him. In his two seasons at Shea, Fregosi batted .233 with just five home runs before being traded to the Texas Rangers.

As for the Angels, they crossed their fingers and hoped for the best from Ryan.

“We picked up one of baseball’s best arms in Ryan. We know of his control problems, but he had the best arm in the National League and, at 24, he is just coming into his own,” GM Harry Dalton said at the time.

It goes without saying the Angels bet on the right horse. In his first season in Anaheim, Ryan was selected to the All-Star team, led the American League in strikeouts and strikeouts per nine innings, walks, hits per nine innings, and shutouts. This was the nightmare the Mets had hoped to never see—their homegrown product blossoming elsewhere.

Would Ryan have become a supernova had he remained in New York? That question will forever go unanswered. Seaver, however, doubted it.

“Nolan was a shy guy who never felt comfortable (with the Mets),” he said. “His talent was obvious, but he was just a kid from Texas who wasn’t ready for the big city. I do believe the environment affected him. He was bound to do better somewhere else.”

There was one other factor that sapped Ryan of his focus: His wife Ruth was even more ill at ease in New York than he was. The two had been high school sweethearts before marrying in 1967, which made it hard enough for the young couple to be apart. But the fact that Ruth was alone in the city was especially worrisome to Ryan when he was on the road with the Mets. He feared for her safety.

The shift to the slower-paced lifestyle in California was a blessing to both Ryans. Not only was Ruth thousands of miles from the urban chaos, but a more relaxed Nolan proceeded to go on a tear that paved the road to Cooperstown. He became a 20-game winner in his second season with the Angels, including two no-hitters while setting a Major League record with 383 strikeouts in 326 innings.

Ryan’s dominance was practically unquantifiable, if not unbelievable. He struck out 10 or more batters in 23 of his 39 starts, even though wildness still dogged him. The right-hander issued 202 walks, making him only the second pitcher since 1900 to surpass the 200 mark. Nevertheless, it was clear the Angels had ended up on the winning side of the trade with the Mets, as Ryan set a career high with 22 wins in 1974 and set an American League record with 332.2 innings. That mark still stands today.

In all, Ryan spent seven seasons with the Angels, threw four no-hitters while averaging 302 strikeouts per year. Thanks to those blistering fastballs and the overall development of his arsenal, Ryan led the Angels to the first playoff appearance in franchise history in 1979. Not surprisingly, he was on the mound in Game 1 of the AL Championship Series against the Orioles, allowing one earned run in seven innings, striking out eight.

Even though the Angels lost in four games—thus keeping Ryan from pitching a fifth and deciding game—he nevertheless raised the Angels’ profile with that one postseason appearance. The next year Ryan signed with the Astros as a free agent, by which point he had become an industry giant.

As for Fregosi, who passed away in 2014 at the age of 71, he ended up making his mark as a manager, winning 1,028 games with the Angels, White Sox, Phillies, and Blue Jays. The trade to the Mets was mercifully forgotten, although Fregosi himself used to joke about it.

“The only thing [Fregosi] did say was, ‘I don’t know what the Mets were thinking, I was done when they made that trade.’ He would always refer back to that,” Larry Bowa, a coach on Fregosi’s staff with the 1993 National League champion Phillies, told reporters after Fregosi’s passing.

Also Check THE DETROIT WOLVERINES, NATIONAL LEAGUE CHAMPIONS!

History will regard the trade as one of the most one-sided trades baseball has ever known. The Angels would happily agree.

Source: Chuck Anderson on Flickr