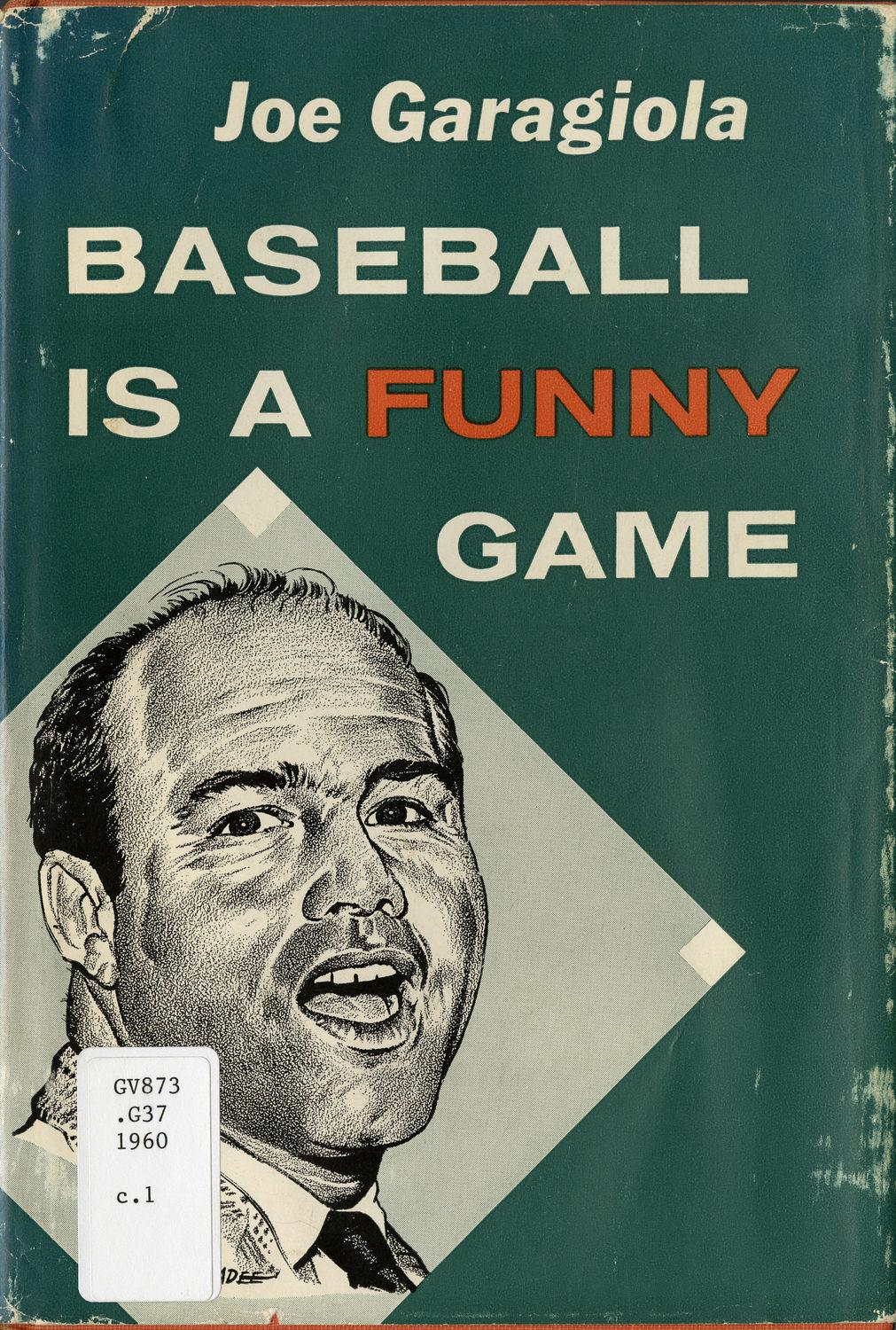

To the extent Baseball Is a Funny Game is recalled today, it is largely for its yarns. This is due in part to the content and in part to the subsequent reputation of the author. When the book hit stores in May of 1960, Joe Garagiola was a little-known retired catcher who had taken up color commentary in St. Louis. His anonymity, however, was about to change.

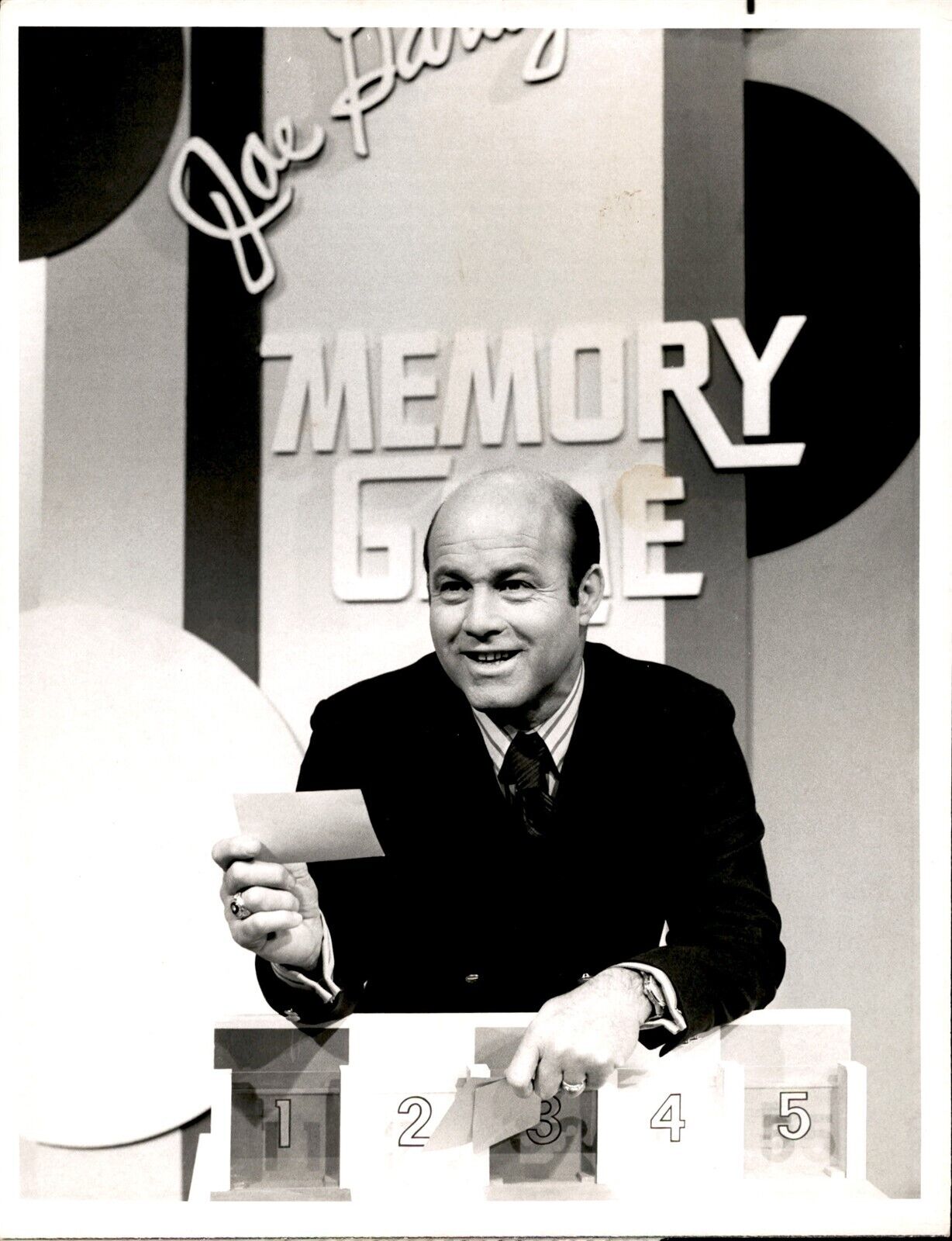

Baseball Is a Funny Game spent much of that summer on the New York Times best-seller list—something unheard-of for a baseball book at the time—earning its author guest stints on the Today Show with Dave Garroway and the Tonight Show with Jack Paar. Both turned out to be perfect vehicles to display Garagiola’s self-deprecating wit and storytelling charm before a national audience. Within a few months, he was doing color—and eventually play-by-play—on NBC’s national “Game of the Week” telecasts.

That national exposure allowed Garagiola to do something rare among sports figures at the time: cross over into the realm of general entertainment. He began showing up regularly on the Today Show in the mid-1960s, and he occasionally guest hosted the Tonight Show for Johnny Carson. From the late 1960s into the 1980s, he was a daytime quiz show fixture, most often on To Tell the Truth or The Match Game.

The irony is that, by modern standards anyway, much of the humor in Baseball Is a Funny Game comes across as tame, and certainly sanitized. Offered to a modern publisher, it might meet with rejection. But in 1960, it presented fans fresh insights into life on the field and in the clubhouse. The Long Season, Jim Brosnan’s breakthrough diary, was still two months from publication in May of 1960, and Jim Bouton’s Ball Four was a decade in the future.

Read retrospectively, the simple wisdom conveyed in Garagiola’s stories, both the humorous and serious ones, shines through. One such lesson, which has stuck with me since I first read it as a teenager, concerns Pepper Martin complaining to Cardinals Manager Ray Blades about the spring training grind. Blades had scheduled two-a-day workouts, the better to hone whatever talent existed on his roster. The extra work did not sit well with Martin, who saw the team’s problem less as one of precision than natural ability. “I got a jackass back in Oklahoma,” Martin told Blades during a clubhouse meeting, “and you can work him from sunup till sundown, and he ain’t never going to win the Kentucky Derby.”

Similar: GRAHAM MCNAMEE, BASEBALL’S FIRST RADIO STAR

It’s simultaneously funny and true. Effort will take you only so far; first you must have talent.

Until Garagiola, baseball books tended to be insiderish, and not especially designed for mass audiences. In 2003, Garagiola told author Marty Appel that he had drawn inspiration for his book from one written by Paul Richards, then a well-known manager. Richards’ book was replete with how-tos, foot movements, curveball grips, and the like. “Geez, the guy driving the 18-wheeler who’s never gonna be a player, these books can’t be for him,” Garagiola said. He decided to write something more down to earth.

His own playing career, nine big league seasons as a regular and then backup catcher, provided most of the stories and lessons. Although hardly a polished academic of the stripe of Brosnan, he completed a manuscript in 1959 and turned it over to Bob Broeg, sports editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, for review. Broeg worked it over, Garagiola worked Broeg’s revisions over, and Martin Quigley, a public relations specialist, recrafted that version into a final manuscript. The end result was something simultaneously literary and true to Garagiola’s folksy charm. Garagiola retained sole authorship credit, although Quigley was co-listed as holder of the copyright, and the book was co-dedicated to Quigley as Garagiola’s “literary coach.”

Similar Articles: RING LARDNER: BASEBALL’S COMEDIC GENIUS

Baseball Is a Funny Game traded in the kinds of clubhouse and front-office stories previously considered sacrosanct, although it did so in a less revealing fashion than, for instance, The Long Season or Ball Four. There are no drug references, no escapades with women, no cursing, and no rowdy off-field behavior. Two stories lifted from the text define the extent to which Garagiola was willing to be risqué. The first involves contract negotiations between Dodgers General Manager Branch Rickey, a committed moralist, and players Gene Hermanski and Chuck Connors. Hermanski went into Rickey’s office first, emerging after an hour and reporting to Connors that he had not signed. As related by Hermanski to Connors, the first player had passed most of Rickey’s tests—he denied smoking or carousing—but his admission to an occasional nip had been too much for the pious general manager to bear. Armed with that knowledge, Connors entered and got his raise based on the following exchange:

Rickey: “Do you smoke?”

Connors: “No, Mr. Rickey.”

Rickey: “Do you go out with women?”

Connors: “No, Mr. Rickey.”

Rickey: “Do you drink?”

Connors (slamming his fist on the table): “If I have to drink to stay in your organization, I’m leaving.”

The second story involves umpire Augie Donatelli and Bobby Thomson reminiscing about the time when Donatelli became the only arbiter ever to throw Thomson out of a game. “I called a strike on you and you called me a ______,” Donatelli recalled.

“That’s right,” said Thomson, “but why did you kick me out for that? Nobody heard it but you and me and the catcher.”

“I didn’t want that catcher going through life thinking I was a______,” Donatelli replied.

Over the decades, a few aspects of Garagiola’s book have grown dated. “While broadcasting in Ebbets Field, I saw a rookie pitcher, Tom LaSorda, get spiked covering home plate,” he recalls in a chapter intended to illustrate the fragility of a ballplayer’s life. That Lasorda fellow’s pitching career didn’t go well—he was 0–4 in 18 appearances covering three seasons—but he did find success in subsequent endeavors. Garagiola’s easy use of the term “dago” would not fly today. Nor does he evince interest in any of the game’s contemporary challenges—notably Jackie Robinson’s 1947 integration of the game—to which he was an eyewitness.

Neither profound in its philosophy nor intellectually groundbreaking, Baseball Is a Funny Game is not usually included today among the essentials in a baseball historian’s library. That does not diminish its cultural importance. Appearing on bookshelves just as Baby Boomers hit their teenage years, it gave baseball a dimensionality the game had to that point often lacked. It also gave the world Garagiola. The book is important for those two reasons if not others.