In the old bat-and-ball games that preceded baseball as we know it, the pitcher sometimes was known as the feeder, who merely tossed the ball softly toward the batter. His role was to initiate the action, which began in earnest when the ball was hit. There was no calling of balls or strikes, and the pitcher kept throwing until the batter connected. In most games, the delivery was underhand, although in early New England baseball the pitcher threw a lighter ball overhand.

Much early activity was of the informal backyard variety with little thought to keeping score. Even if tallies were recorded, there was no serious consequence to winning or losing. By the middle of the 1850s, however, interclub competition had begun and results, as a matter of pride and prestige, had become more important. Pitchers therefore began looking for ways to gain advantages for their team.

The only legal restrictions on the pitcher were that he not step over a line 45 feet from home plate, that he deliver the ball from below the hipline and that he “pitch” and not throw the ball. Pitchers began to take a running approach to the 45-foot line and to test the limits of a “fair pitch.” The distinction between a pitch and an illegal throw was a fine one, based upon whether the pitcher held his wrist rigid or delivered the ball with a snap of the wrist.

Jim Creighton, baseball’s first superstar and possibly its first professional player, has been credited with revolutionizing the art of pitching, but he was not the first to use a faster delivery to prevent batters from hitting the ball solidly. By the mid-1850s, there were numerous reports of pitchers adding speed. Fast pitching had its limits, however, for catchers had no gloves and lacked protective equipment. Few were able to consistently handle a swiftly thrown ball, especially if the pitching was not accurate.

Creighton had his greatest moments with the 1860 Excelsior Club of Brooklyn, which undertook baseball’s first tour and engaged in a bitter tussle with the Atlantics for the national title. Creighton had an unusual delivery, releasing the ball with his hand very close to the ground so that it appeared to rise as it approached the batter. One of the reasons for his success was that his catcher was Joe Leggett, perhaps the finest backstop of the late ‘50s. Without Leggett supporting him, Creighton’s speed would have been remarkable but ineffective.

Creighton’s success spawned a number of imitators, most of whom lacked his control and did not have an agile catcher like Leggett. This led to wild pitches and long, tedious games. Earlier, a century and a half before the modern obsession with pitch counts, it was not uncommon for a hurler to make 200 or 300 pitches. In the second game of the Fashion Course All-Star series in 1858, Tom Van Cott of New York threw 270 pitches and Frank Pidgeon of Brooklyn 290. In the third game, Pidgeon threw 436 pitches, including 87 in the first inning. That same year, Canfield of the Resolutes threw 128 pitches in a single inning.

By the 1860s, both batters and pitchers were taking advantage because balls and strikes were not called. Batters waited interminably as pitch after pitch sailed by to give runners a chance to steal a base and to frustrate the pitcher. Pitchers threw beyond the reach of batters hoping they would eventually become impatient and swing at a bad pitch.

In response to the tedious play that resulted from such cat-and-mouse games, the rules committee of the National Association took measured steps toward the calling of balls and strikes. The intention was to punish the pitcher for intentionally throwing wide of the plate and the hitter for repeatedly letting good pitches pass. In the beginning, there was no intention of calling a ball or strike on every pitch. First there were warnings. If these were not heeded, balls and strikes were called.

Before the 1864 season, the rules were significantly amended to counter the emergence of the pitcher as a defensive weapon. The rules committee established a 3 × 12-foot pitching box, which prevented the pitcher from getting a running start. He was also required to deliver the ball with both feet on the ground, limiting his leverage and therefore his speed. Umpires were strongly encouraged to call balls if the pitcher repeatedly failed to deliver “fair” balls, which were defined in terms of the batters’ reach rather than having to cross home plate.

Once umpires became accustomed to them, the rule changes eliminated the “waiting game,” but fast pitching was not discouraged because it had proven effective. By the middle of the 1860s, the pitcher who relied on slow tosses and strategy, such as Alphonse Martin, was a rarity. Nearly all the top pitchers threw as fast as their catchers could tolerate.

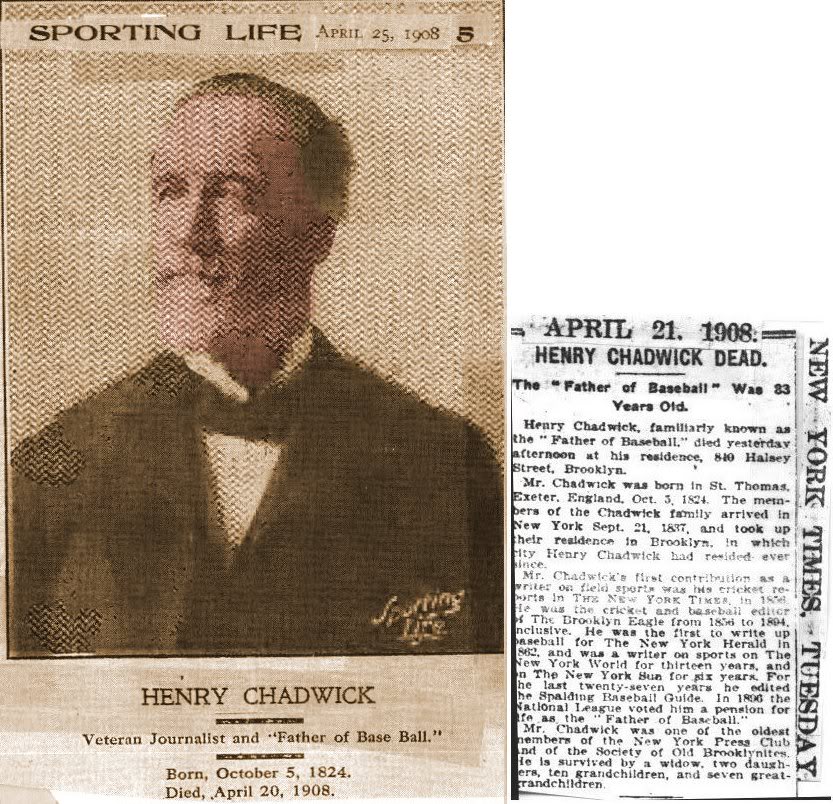

The limitations on pitching resulted in a lot of runs. Strikeouts were rare, fielding without gloves was challenging, and a lot of action occurred when the ball was put in play. Legendary journalist Henry Chadwick wanted to place limits on the pitcher but was rapturous over low-scoring games that resulted from top-notch defense. He deplored fast pitching, believing that skillful fielding was the most attractive feature of baseball and one that couldn’t be exhibited if the battery merely played catch.

During the era of the professional National Association (1871–1875), pitchers threw hard and not always straight. Some threw a rudimentary curveball, with many claiming to be its originator. Arthur “Candy” Cummings won election to the Hall of Fame by claiming to have invented the curve, but some think another hurler, perhaps Bobby Mathews, was the first.

In 1872, the rules committee legalized the underhand snap throw, acknowledging a state of affairs that already existed. The principal pitching weapons of the NA pitcher were speed, control, and the ability to change speeds to keep the batter off balance. Al Spalding of the Boston Red Stockings and Dick McBride of the Athletics were probably the two best pitchers of the NA era. Spalding, who won 204 games in five years, never threw a curve, relying on speed, control and the support of the league’s dominant team.

NA teams didn’t play every day; the league’s schedule ranged from 25–35 games per team in 1871 and increased to 70–90 in 1875. Most teams relied on a single hurler, with a “change” pitcher used against weaker teams or when the regular was fatigued. Field captains realized there was an advantage to replacing a fast pitcher with a slow one and vice versa to disrupt the timing of the opposition, but strategic use of a relief pitcher was many years in the future. Spalding completed 226 of his 264 NA starts and threw a high of 617 innings in 1874. With a relatively dead ball and distant fences, home runs were rare, and it was not necessary for a pitcher to bear down on every delivery. Further, the underhand delivery and the fact that Spalding frequently had a sizable lead rendered his workload more tolerable, but 617 innings is still 617 innings.

With the advent of the National League and the American Association, the number of games per season increased, and by the 1880s most teams had two regular pitchers. Still, hurlers worked a lot of innings, with the iron man class typified by Hoss Radbourn’s 1884 season. As Providence’s only reliable pitcher the second half of the year, Radbourn completed all 73 of his starts, threw 6792/3 innings and won 59 games. But what was so remarkable about that? Sporting Life commented, “What is the work of a first-class League pitcher during a season’s campaign? Why nothing more than nine innings of pitching once a day—occupying less than two hour’s labor out of the twenty-four—during an average of four days a week. Why it is simply nonsense to assert that this is an arduous task for any man of the healthy class of athletics who compose the leading pitchers of the day. What Radbourn has done they can all do.”

By 1884, the rules were different from the 1870s. National League pitchers could throw from any angle, but American Association hurlers were limited to deliveries below the shoulder. The increased freedom put a strain on both pitchers and catchers. Sporting Life’s opinion notwithstanding, the 29-year-old Radbourn’s constitution was greatly taxed in 1884, and his arm was painfully sore most of the season. By that time, catchers had some protective equipment, including gloves, masks, and chest protectors, but the punishment they endured was almost inhuman. Broken fingers were common, there were undoubtedly many undiagnosed concussions and yet the hardy men behind the bat soldiered on.

The rule changes also were difficult on hitters. There were innumerable shutouts in 1884 and eight no-hitters, compared to 11 combined in the years from 1871 to 1883. Chadwick predictably decried the lack of offense and this time he had company, for watching strikeouts was not exciting. The pitcher and catcher had become the two most important players on each team. Pioneer player George Wright reminisced fondly about the era when the fielders were most important and pitchers were secondary. The preponderance of prima donna pitchers prompted Sporting Life to declare, “Less care for the pitcher and more for the batsman is what is needed. With a return to the first principles, it will be impossible for a few cranky pitchers to break up an entire team.”

The game was in danger of becoming unbalanced, and changes were eventually made that increased the pitching distance to its present length of 60 feet, 6 inches and curbed the dominance of the pitcher. The result was an increase in offense during the final decade of the 19th century that led to the dead ball era of the early 20th. That was followed in turn by the home run explosions of the 1920s and the peak offensive year of 1930, when the entire National League batted .303.

The offensive doldrums of the mid-1960s culminated in the Year of the Pitcher in 1968, when American League hitters averaged .230 and pitchers won MVP awards in both leagues. Three decades later, the steroid era and record home run totals saw batters once again in the vanguard. Since the emergence of Jim Creighton, baseball rule makers have waged an unending battle to achieve balance between his descendants and those who bat against them.