As we wait for those magic words of February, “pitchers and catchers report today,” we can reflect that the influence of baseball on the English language is stunning, strong, and at what appears to be an all-time real and metaphoric high. Tough folks play “hardball,” save for when they relent and ask a few “softball questions.” Everyone seems to be willing to settle for a “ballpark figure,” and there are still a lot of folks who ask you to “touch base” with them. We sympathize with those who “can’t make it to first base” or are “out in left field.” Retailers who run out of sale items often offer us “rain checks.” Beginners are “rookies,” those who easily master a given skill are called “naturals,” and those who seem eccentric are labeled “screwballs.”

This creeping baseballese began its encroachment on the American language years ago. “No other sport and few other occupations have introduced so many phrases, so many words, and so many twists into our language as have baseball,” wrote Tristram Potter Coffin in his 1971 study of baseball folklore, The Old Ball Game. “The true test comes in the fact that old ladies who have never been to the ballpark, coquettes who don’t know or care who’s on first, men who think athletics begin and end with a pair of goalposts, still know and use a great deal of baseball-derived terminology.”

But Coffin wrote his book before the term “inside baseball” gained popularity outside baseball as a way of describing inner-sanctum goings on. It was also written in a simpler time when Yogi Berra was still a mere mortal. Today, he seems to be quoted—“It’s deja vu all over again,” “If you come to a fork in the road, take it,” etc.—more often than Oscar Wilde, George Bernard Shaw, and Bertrand Russell put together. It was also a time before baseball terms worked into international play via the World Wide Web—the term “southpaw” yields more than 6 million hits when entered into the Google search engine while “rookie” racks up more than 117 million.

In terms of familiar allusions, the classic Abbott and Costello “Who’s On First?” comedy routine seems to be becoming more, rather than less, popular over time because of cyberspace. There are several versions of the original routine on YouTube that have been viewed more than 4 million times, and millions more have watched the sequel acted out in 2012 by Jimmy Fallon, Billy Crystal, and Jerry Seinfeld on The Tonight Show.

Any way you look at it the number of everyday terms that come from baseball is large. Perhaps the best way to drive this home is to present a partial list of terms and phrases that started in baseball (or, at least, were given a major boost by it) but that have much wider application, to wit: A team, ace, Alibi Ike, Annie Oakley, back-to-back, ballpark figure, bat a thousand, batting average, bean, bench, benchwarmer, Black Sox, bleacher, bonehead, boner, box score, the breaks, breeze/breeze through, Bronx cheer, bunt, bush, bush league(r), butterfingers, charley horse, choke, circus catch, clutch, clutch hitter, curveball, doubleheader, double play, extra innings, fan, fouled out, gate money, get one’s innings, get to first base, go to bat for, grandstander, grandstand play, ground rules, hardball, heads up, hit and run, “hit ’em where they ain’t,” hit the dirt, home run, hot stove league, hustler, in the ballpark, in a pinch, in there pitching, “it ain’t over ’til it’s over,” “it’s a (whole) new ball game,” jinx, “keep your eye on the ball,” Ladies’ Day, Louisville Slugger, minor league, muff, “nice guys finish last,” ninth-inning rally, off base, on-deck, on the ball, on the bench, out in left field, out of my league, phenom, pinch hitter, play ball with, play the field, play-by-play, rain check, rhubarb, right off the bat, rookie, rooter, Ruthian, safe by a mile, “say it ain’t so, Joe,” screwball, seventh-inning stretch, showboat, shut out, smash hit, southpaw, spitball, squeeze play, Stengelese, strawberry, strike out, sucker, switch hitter, team play, Tinker to Evers to Chance, touch all the bases, two strikes against him, “wait ’til next year,” whitewash, “Who’s On First?”, windup, “you can’t win ’em all,” “you could look it up.”

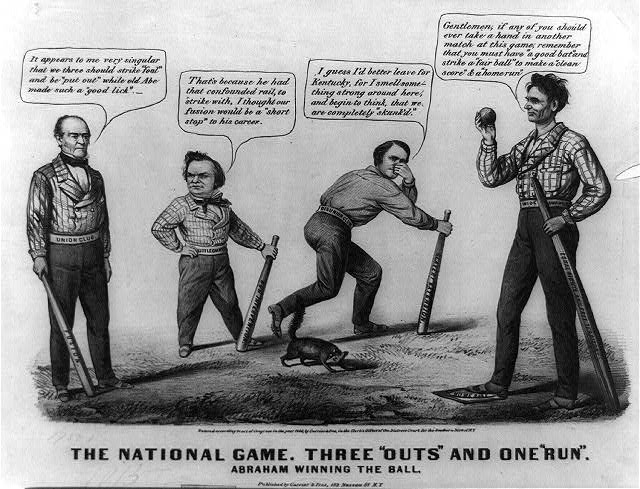

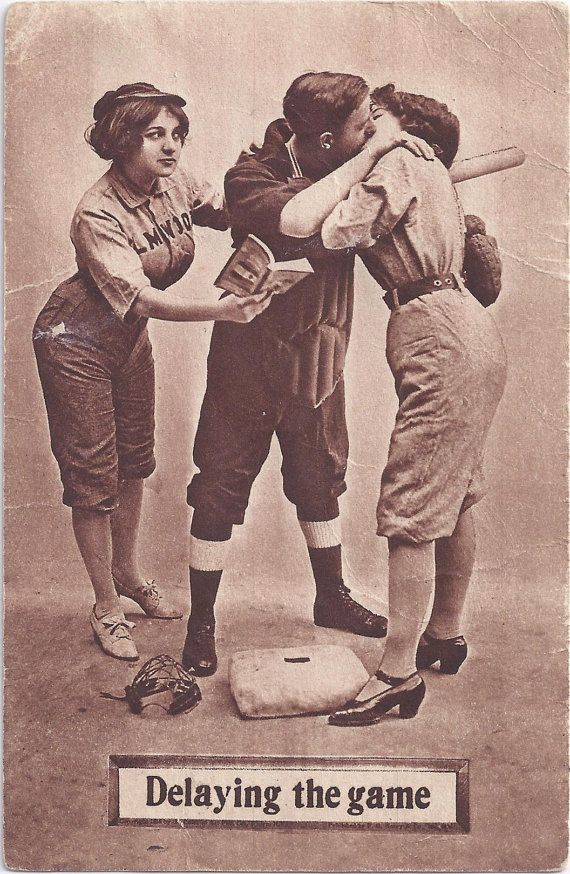

Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003674584/

Elting E. Morison, writing in American Heritage (August/September 1986), asked, “Why is baseball terminology so dominant an influence in the language? Does it suggest that the situations that develop as the game is played are comparable to the patterns of our daily work? Does the sport imitate the fundamentals of the national life or is the national life shaped to an extent by the character of the sport?” He answered, “In any case, here is an opportunity to reflect on the meaning of what I think I heard Reggie Jackson say in his spot on a national network in the last World Series: ‘The country is as American as baseball.’”

As the author/compiler of the Dickson Baseball Dictionary, I have had decades to ponder this transfer of baseball terminology and slang to the situations of everyday life. Here is why I think this happened—and is still happening.

First and foremost, the extent of baseball terminology in the language is enormous. The first edition of my Dictionary, published in 1989, had 5,000 entries; the second, 10 years later, had 7,000, and in the most recent edition published in 2009 there were 10,000 entries tightly packed into what one reviewer called “a 974-page doorstop of a volume.” The total number is much higher if you count definitions rather than entries. In the third edition, there are 15 baseball meanings for “hook,” 13 for “slot,” 11 each for “break,” “jump,” and “cut.” My chief editor of the book, Robert “Skip” McAfee, and I are already compiling new baseball terms for the fourth edition now penciled in for 2019. (An example: “slash line” is new baseball slang for batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging average written as, for example, .331/.393/.435—a very nice slash line.)

The point is that there was an extensive vocabulary out there to borrow from. “Hit and run,” to pick just one example, was a baseball term for a particular play that dated back into the late nineteenth century but was adopted to describe a vehicular felony in the 1920s. A less gruesome example is contained in the term “flyswatter,” coined by Dr. Samuel J. Crumbine, who in 1904 was appointed head of the Kansas State Board of Health. Crumbine was taking a bulletin—on flies as typhoid carriers—to the printer one day and stopped off to watch a ballgame, where he heard “sacrifice fly” and “swat the ball,” etc., and immediately decided to call the bulletin “Swat the Fly.” Only a few months later a man came to him with an instrument that he wanted to call a “fly bat,” and Dr. Crumbine persuaded him to call it a “flyswatter.” The man in question was Frank Rose whose son, Bob, retold the story in Reminisce magazine (Sept.–Oct. 1992), adding that his father was a schoolteacher in Weir, Kansas, when he read of Crumbine’s anti-fly crusade. The doctor’s literature gave him an idea. “My father was a scoutmaster at the time, so he had plenty of help for any civic project he chose to take on. He acquired some yardsticks and screen wire from the local lumberyard. Then he had his scouts saw the yardsticks in half, cut the wire into small squares, and nail them together. The scouts decided to call their creations ‘fly bats.’”

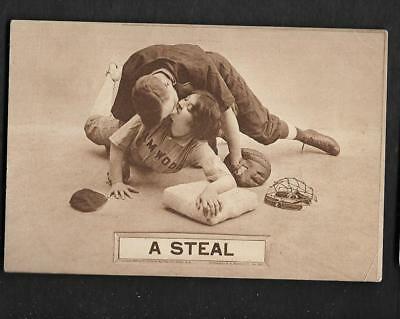

Then there is the fact that during the game’s formative years the newspapers developed and defined their own baseball slang, which was adopted by the fans. Then came radio, which did more of the same. The slang of the game infatuated and educated several generations of young Americans who learned to define their successes and failures in life—including romance—in terms of batting averages and progress around the bases.

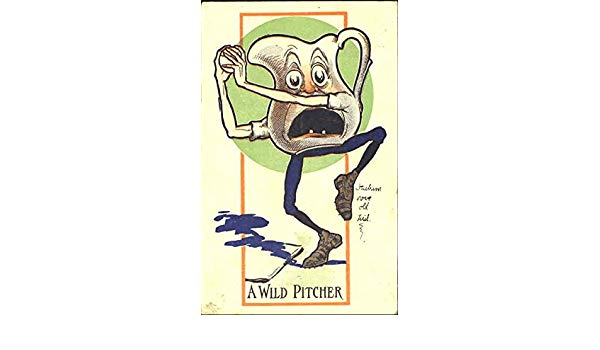

Credit: http://www.net54baseball.com/

For the young, baseball slang was especially appealing as it was sometimes frowned upon by their elders. In the early part of the twentieth century an odd movement started whose purpose was to actually suppress baseball slang. Time has obscured some of the details, but what it amounted to was a movement toward linguistic purity and away from sports page baseballese at a time when it was booming and those outside fandom were confused. Important voices—Collier’s Weekly and the New York Tribune—were early leaders of the crusade.

In 1913 the Chicago Record-American began covering games two ways: one in the slang of the time and, next to it, a description of the game in “less boisterous” terms. A Professor McClintock of the English Department at the University of Chicago brought the matter to national attention when he suggested that the Republic would be better served if baseball slang were dropped and that, for starters, the newspapers would start describing the sport in dictionary English.

This call came at a time when, for example, The Washington Post’s Joe Campbell, “the Chaucer of baseball,” would write: “And Amie Rusie made a Svengali pass in front of Charlie Reilly’s lamps and he carved three nicks in the weather,” to say that Rusie had gotten Reilly to strike out.

A few managers and players actually agreed with McClintock, but there was little sympathy expressed by the press, which whipped McClintock’s notion into something big. “The question has assumed the importance of a national issue,” said an editorial in the Charleston News and Courier. “It has received editorial discussion in the columns of the most influential newspapers, and it has aroused interest from end to end of this baseball-loving land.” Calling the notion the “injury which is now proposed,” the paper went on to say: “It is to be hoped, and it may reasonably be expected, that the movement will not accomplish the results which its more radical advocates desire. Baseball stories told in conventional English are dull reading indeed; and it is a pertinent fact that the decadence of cricket in England is attributed by many British newspapers to the failure of the press to put brightness or ‘ginger’ into the descriptions of the game.”

The Washington Post chose to make fun of McClintock by describing play using dictionary English. Sample: “Johnson gave the batter a free pass to first” becomes “Mr. Johnson pitched four balls that in immediate sequence made a detour of the plate, which, according to the rules of the game, entitled the batter to go to first base, despite the fact that he had not even aimed his bat at the baseball in any one instance.” After a thorough roasting, the Post concluded: “Much of the English used by Professor McClintock himself was once regarded as slang.”

Credit: Andy Moresund Collection