If remembered for anything today, the Highlanders of New York are recollected as predecessors to the Yankees. Occupying by modern standards a bandbox of a ball park in the highest part of Manhattan, the team’s name reflected its location.

If one were able to ask clubhouse manager Fred Logan what was most memorable about the Highlanders, he might well have said Jack Chesbro and Walter Johnson. In any ranking of the all-time greatest pitching feats, it would be hard to disagree with what Logan witnessed on the pitcher’s mound at Hilltop Park in 1904 and 1908.

Logan tended in 1904 to the needs of strong right-hander “Smiling” Jack Chesbro, who would compile one of the most astounding seasons in the history of the game with 51 starts, 48 complete games, a 41-12 record and a 1.82 ERA built around 239 strikeouts in 454 innings.

The Highlanders ace’s record for games won in baseball’s post-1900 era has stood for over a century, one of the oldest major individual marks in any sport. What is usually forgotten, or simply not mentioned, is that for all of Jack’s winning, his season would be best/worst? defined by the last of his dozen losses.

The 1904 season started with a Highlanders victory over the defending American League champion Boston Pilgrims (later the Red Sox) in New York before 15,000 fans who braved a snowstorm to see the great Cy Young touched for five first-inning runs in an 8-2 victory for the home club. But this season of hope would end in a decidedly different fashion.

You Might Also Like: Best Youth Baseball Bats 2019

Here’s how the New York Times described the scene at Hilltop Park when a crowd estimated at 12,000 more than the stadium held turned out to root their heroes to an anticipated pennant-clinching victory in a season-ending doubleheader between the first-place Pilgrims and second-place Highlanders.

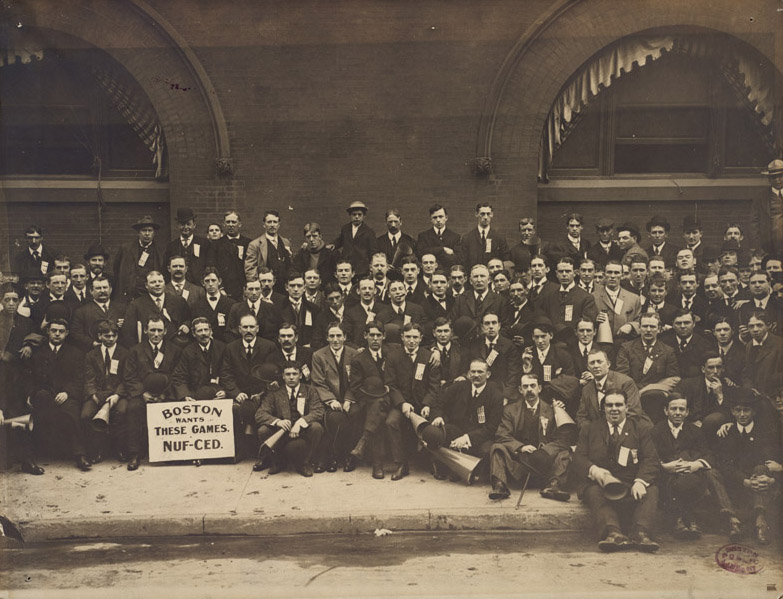

Probably no such interest ever was taken in a baseball event in this city as was manifested in the double-header of yesterday. Some 200 Boston “rooters,””accompanied by Dockstader’s Band of this city, had the extreme left end of the grand stand to themselves, and with the aid of the band, megaphones, and tin horns kept a constant din throughout the nine innings.

The Highlanders needed to sweep the double bill to take the pennant; Boston needed to merely win one game to successfully defend its title. The 200 Beantown fans on hand, accompanied by their hired New York band, bravely went up against the rest of the 28,000 spectators. Their rooting was rewarded with a close contest that saw their heroes score two in the seventh inning on errors by New York second baseman Jimmie Williams to match New York’s two fifth-inning runs.

Boston’s Lou Criger opened the top of the ninth with a single. Ace pitcher Bill Dineen, who finished all 37 games he started that season, bunted Criger to second. After moving to third on the second out of the inning, Criger scored on a wild pitch by the usually reliable Chesbro.

Two Highlanders walks in the bottom of the ninth were wasted when Dineen struck out Patsy Dougherty, leaving the potential tying and winning runs on base. The Pilgrims were champions again, with New York a frustratingly close second. For all of Chesbro’s 41 victories, the game that counted the most was the last one that got away. The gloom in Fred Logan’s clubhouse must have been palpable.

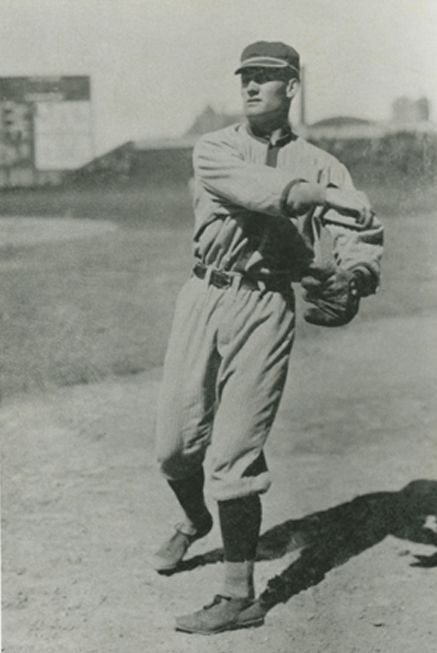

Four years later, another remarkable pitching mark was compiled at Hilltop Park. As that 1908 season wound its way down in September, strikeout specialist Walter Johnson of the Washington Nationals shut out the Highlanders three times in four days.

Johnson began with a 3-0 five hitter on Sept. 4, followed by a 6-0 three-hitter the next day. Seemingly, only New York’s blue law prohibiting baseball on Sundays prevented the Big Train from repeating the feat on the 6th. He took the day off but resumed his complete mastery of the Highlanders with a 2-0 two-hitter on Labor Day. Over 27 innings, Johnson allowed 10 hits and zero runs.

According to legend, Walter hid in the clubhouse when Washington manager Joe Cantillon was looking for a starter for Tuesday’s game. A New York newspaper described this, presumably with editorial tongue in cheek:

We are grievously disappointed in this man Johnson of Washington. He and his team had four games to play with the champion [sic] Yankees. Johnson pitched the first game and shut us out. Johnson pitched the second game and shut us out. Johnson pitched the third game and shut us out. Did Johnson pitch the fourth game and shut us out? He did not. Oh, you quitter! Most pitchers would have gone on and taken a chance after this demonstration of comparative strength. But did Johnson? No Sir. He weakened. He passed up the fourth game, refusing to sit in as slabsman, and another Washingtonian named Youse, according to umpire Evans, and spelled Hughes, according to the [score]card, pitched the final of yesterday’s doubleheader, and beat the local wonders even worse than is customary. Oh, rare Pitcher Johnson! Why did you not preserve your record intact? Oh, thou of little faith.

Fred Logan began his clubhouse career as a youngster of 12 in 1890 in the Polo Grounds, home of the New York Giants. In 1903, he signed on with the new Highlanders as they brought a sorely needed substance to Ban Johnson’s two-year-old American League. Logan was there on the inside when the Highlanders became the Yankees in 1913 and when the “House That Ruth Built” opened in 1923 as baseball’s premier palace. He, along with son Ed, would serve both the Giants and the Yankees through the 1946 season.

J.G. Taylor Spink, writing in 1938 in The Sporting News, told us, “The elder Logan has been connected with New York clubhouses since August 1889. His story practically bridges the history of baseball. Logan has seen more major league players in their off-the-field hours than any other man now alive.”

It is doubtful that in all those seasons in the sun from 1889, when as a lad of 11 he ran an errand for John Montgomery Ward, and shortly thereafter went from go-fer to clubhouse manager, to his final season in the Yankees clubhouse in 1946, he would have seen any pitching feats to equal those of Happy Jack in 1904 and the Big Train in 1908.

Although the Highlanders did not officially become the Yankees until 1913, when the team left Hilltop Park and moved into the Polo Grounds as tenants of the Giants, the shorter nickname was widely used in earlier headlines and stories.