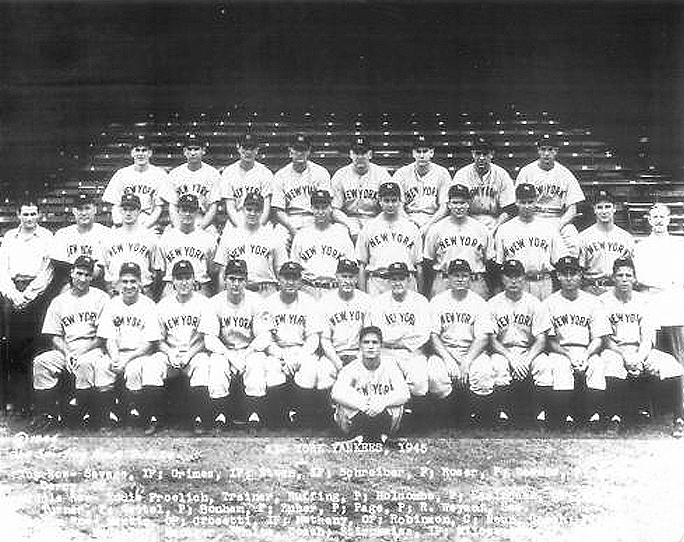

A lot of batboys have “made good” in life, and no doubt the responsibilities instilled in them during those teen years have been a factor. But Tom Villante, who was the New York Yankees batboy in 1944–45, has had a dazzling career, largely in and around baseball, in the years since.

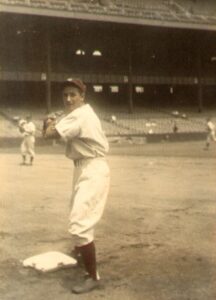

The son of a barber, he was a student at Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan when his friend Chester Palmieri asked him to fill in for him during the 1943 World Series—as visiting team batboy. Palmieri had an exam and could not make the game.

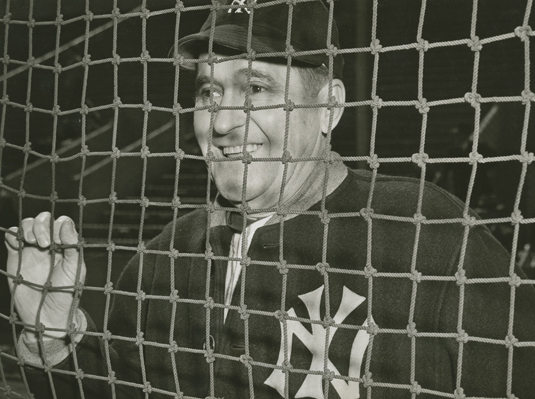

Tom wore a St. Louis Cardinals uniform, filled in capably, and asked about a regular position for 1944. He was interviewed by Clubhouse Manager Fred “Pop” Logan (who went back to 1903 with the franchise), and then by Yankees Manager Joe McCarthy himself, and was offered the job. (He was known as “Commie” Villante then, a nickname for Carmelo, but Commie became Tommy for obvious reasons in the 1950s.)

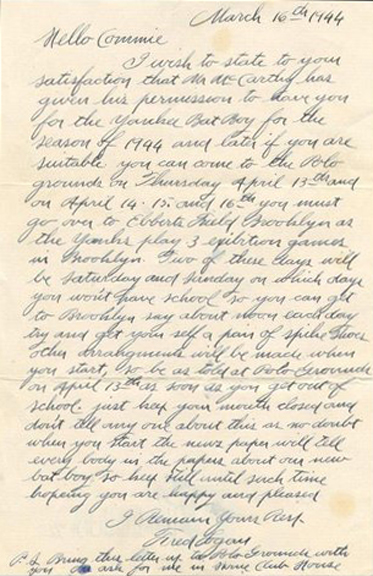

Dear Commie:

I wish to state to your satisfaction that Mr. McCarthy has given his permission to have you for the Yankee Bat Boy for the season of 1944 and later if you are suitable. You can come to the Polo grounds on Thursday, April 13th and on April 14 -15- and 16th. You must go over to Ebbets Field Brooklyn as the Yanks play 3 exhibition games in Brooklyn. Two of these days will be Saturday and Sunday on which days you won’t have school so you can get to Brooklyn say about noon each day. Try and get yourself a pair of spike shoes. Other arrangements will be made when you start, so be as told at Polo Grounds on April 13th as soon as you get out of school. Just keep your mouth closed and don’t tell anyone about this as no doubt when you start the newspaper will tell everybody in the papers about our new bat boy. So keep still until such time. Hoping you are happy and pleased.

I Remain Yours Truly,

Fred Logan

P.S. Bring this letter up to Polo Grounds with you. Ask for me in the home Club House.

Courtesy Tom Villante

Although batboy during the war years (no World Series checks for the Yankees), he made a nice impression on McCarthy during batting practice for his athletic ability. The Yankees deemed him a “prospect” and arranged for him to receive a scholarship to Lafayette College, with an eye on possibly playing second base for them one day. Alas, by the end of college, McCarthy was gone and Casey Stengel had Billy Martin in mind for second base.

So Tom went off to join BBDO, the advertising agency loosely portrayed on Mad Men, and he soon headed the Schaefer Beer account, creating the “Schaefer Circle of Sports” (for all New York sports) and producing Brooklyn Dodgers baseball telecasts.

Tom was among the first to know that Walter O’Malley was thinking about moving to Los Angeles—and he would accompany the Dodgers there, as the BBDO representative overseeing local advertising rights. (Schaefer wasn’t sold on the West Coast, but they retained advertising rights.)

O’Malley hinted at moving for lucrative pay-TV rights, which he felt he couldn’t get away with in Brooklyn, where free baseball on TV was the accepted norm, and he had the Yankees and Giants airing games.

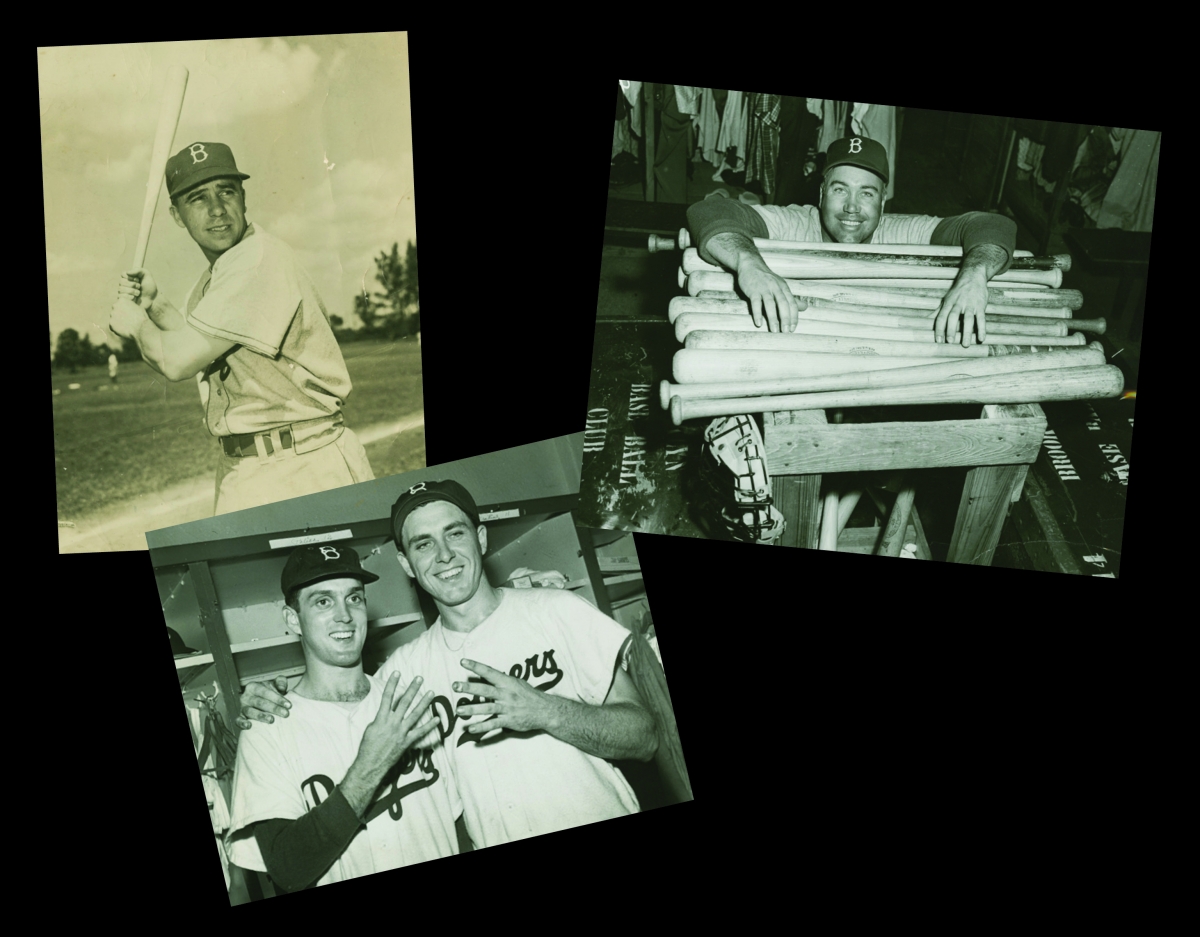

By now, Tom was close friends with a number of Dodgers—these were their star years—and he put together a group called the Flock Syndicate (flock was a nickname for the Dodgers going back to the days when they were the Robins—get it?).

The Flock Syndicate consisted of Tom, Pee Wee Reese, Duke Snider, Gil Hodges, and Carl Erskine. They each put in $500 (out of their 1955 World Series money) and invested in a pay-TV company in LA called Skiatron. Unfortunately, it was not the company that got the business, so that was a deal that didn’t work out.

“We could throw a dart at the stock market and come up with a winner,” said Snider, “but O’Malley and Villante touted Skiatron.”

In true Mad Men fashion though, Tom married a beautiful model (Ralph Branca and Jackie Robinson were at the wedding) and continued to oversee the Schaefer account, including when they became a Yankee sponsor in the early ’70s. In 1973, he oversaw the creation of the logo for use in the final year of the original Yankee Stadium.

In 1968, Major League Baseball asked BBDO, with Tom in the lead, to oversee the Centennial of Baseball celebrations, coming up in 1969, including the logo (which is still the MLB logo), posters, record album, and the banquet and White House visit in Washington, D.C., around the All-Star Game.

Tom finally left BBDO to become vice president of broadcasting and marketing for MLB, where he created “Baseball Fever—Catch It!” (His cars today have BBFEVER and CATCHIT as license plates.) He oversaw a number of advancements in the way baseball was presented nationally, and on several occasions he told George Steinbrenner, “Some day, teams are going to have their own networks.” (Hello to the YES Network.)

Although he was no longer in Los Angeles with the Dodgers, he remained “family” during the O’Malley years, bought a home in Vero Beach, and had the run of Dodgertown, the team’s spring training facility.

When his time at MLB ended, he went back on his own (but with an office at BBDO), where he consulted for a number of Major League teams and developed a syndicated television feature, Yogi at the Movies, in which Yogi Berra did movie reviews, and a syndicated radio program for Tommy Lasorda.

When this author needed a title for his history of the Yankees, he called on Villante for “something that says Yankees, success, and that this is a serious history.” It took Tom 20 minutes to call back with “Pinstripe Empire” and 13 other ideas.

Still an avid golfer and someone who will easily drive in from his home in Westchester County for Papaya King hot dogs with friends (eaten in his car), he entertains an online faithful with chapters from an anecdotal autobiography called Me and Alphonse, about the adventures he and his pal Alphonse Normandia enjoyed while working together at BBDO. Alphonse was the art director who knew little about sports but would happily accompany Tom on lunches with Joe DiMaggio, Don Zimmer, Lasorda, and many other “characters.”

In his 80s, Tom is still a force of nature, full of ideas and observations, among the first to try new computer technology, rather than be intimidated by it, and among the first to note a new feature on a telecast and critique it.

When asked how he is, he invariably answers, “TERR-iffic,” and indeed, that is a good description of a productive life well led.